Click here to access this dispatch as a formatted PDF.

While it led to an extraordinary acceleration in growth, the economic liberalization set in motion by India’s 1991 crisis remains unfinished. Wide swaths of the economy are still constrained by anti-competitive, statist controls that severely distort the allocation of labor, land, and capital. The payoff from another sweeping overhaul of economic policy is potentially enormous – including speeding the rise out of poverty of hundreds of millions of people.

This report explores the areas in which the economic liberalization unleashed by India’s 1991 crisis remains a work in progress, and examines the potential gains from a second phase of transformative reforms. This dispatch delves into the parts of India’s economy with the greatest unrealized potential: agriculture, land, labor, state-owned companies, and the banking system. It concludes with an assessment of the potential boost to India’s growth from a new round of reforms. Additionally, appendices to this report provide a primer on productivity, as well as an explanation of the methodology behind our estimates of further reforms’ prospective contributions to faster economic growth.

Introduction: India’s unfinished revolution

The 1991 crisis threw unprecedented momentum behind a whirlwind of previously-unthinkable reforms, from the abolition of the License Raj to the admission of foreign investment. These policy overhauls largely freed India’s markets for products, enabling companies to produce what they wanted, how they liked.

A previous two-part series provided a chronology of the lead-up to India’s 1991 crisis (“India before 1991: tiger caged”) and the reforms unleashed by that year’s events (“India since 1991: tiger uncaged”).

Economic liberalization had largely stalled by the mid-1990s, however, as a string of scandals marred the final months of Narasimha Rao’s administration. No single party won a majority of seats in Parliament in India’s five subsequent general elections (in 1996, 1998, 1999, 2004, and 2009), which produced a series of unwieldly coalition governments. While they kept India on the path of liberalization with intermittent, piecemeal reforms, these coalitions lacked the political capital to champion another round of sweeping, transformative economic changes.2 For example, even Manmohan Singh (prime minister 2004-2014) – Rao’s finance minister and right-hand man during the post-1991 barrage of reforms – “turned cautious and conservative” when he himself reached India’s highest political office, squandering “precious time staving off inquiries and defending indefensible ministers”.3

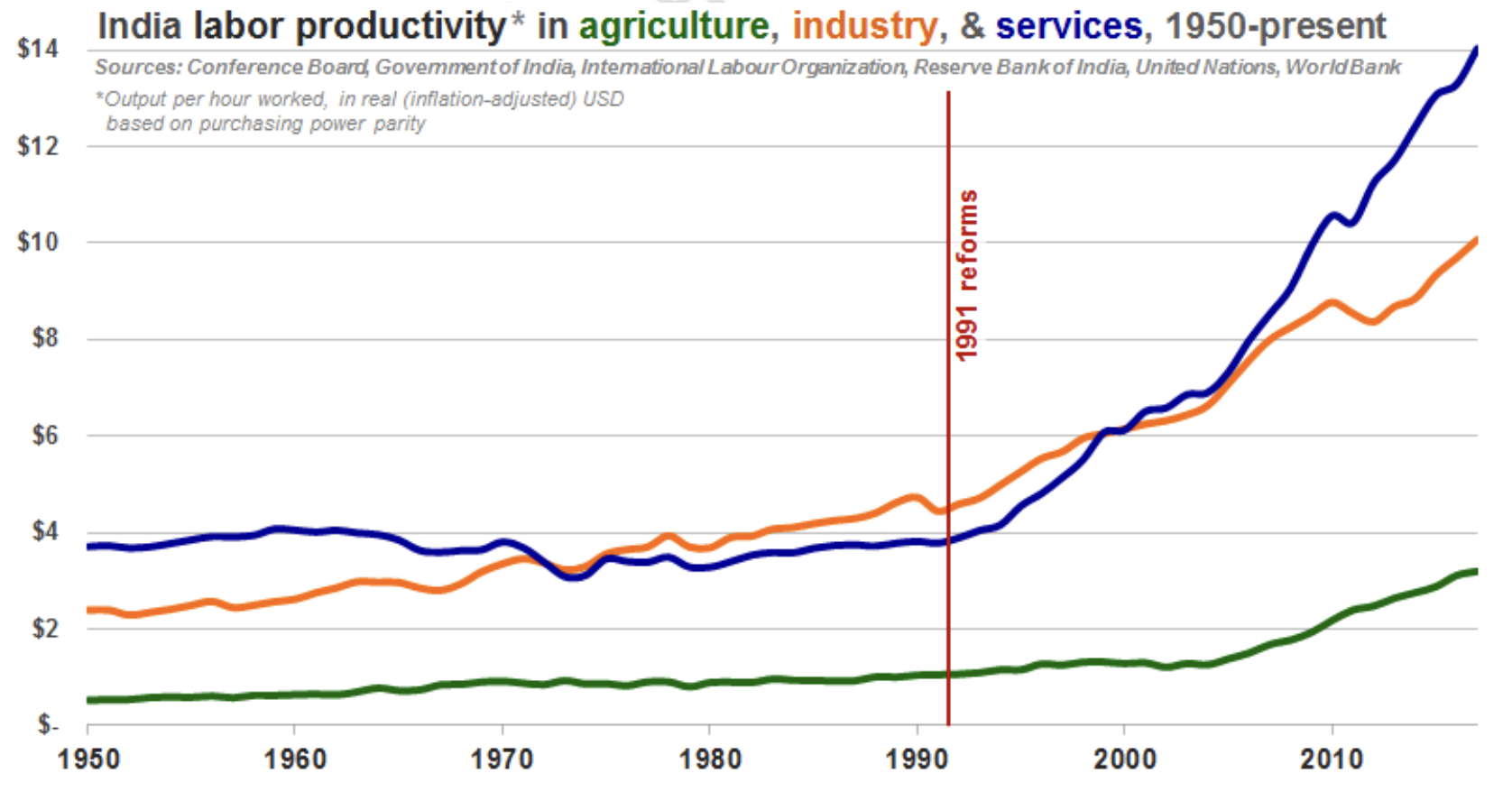

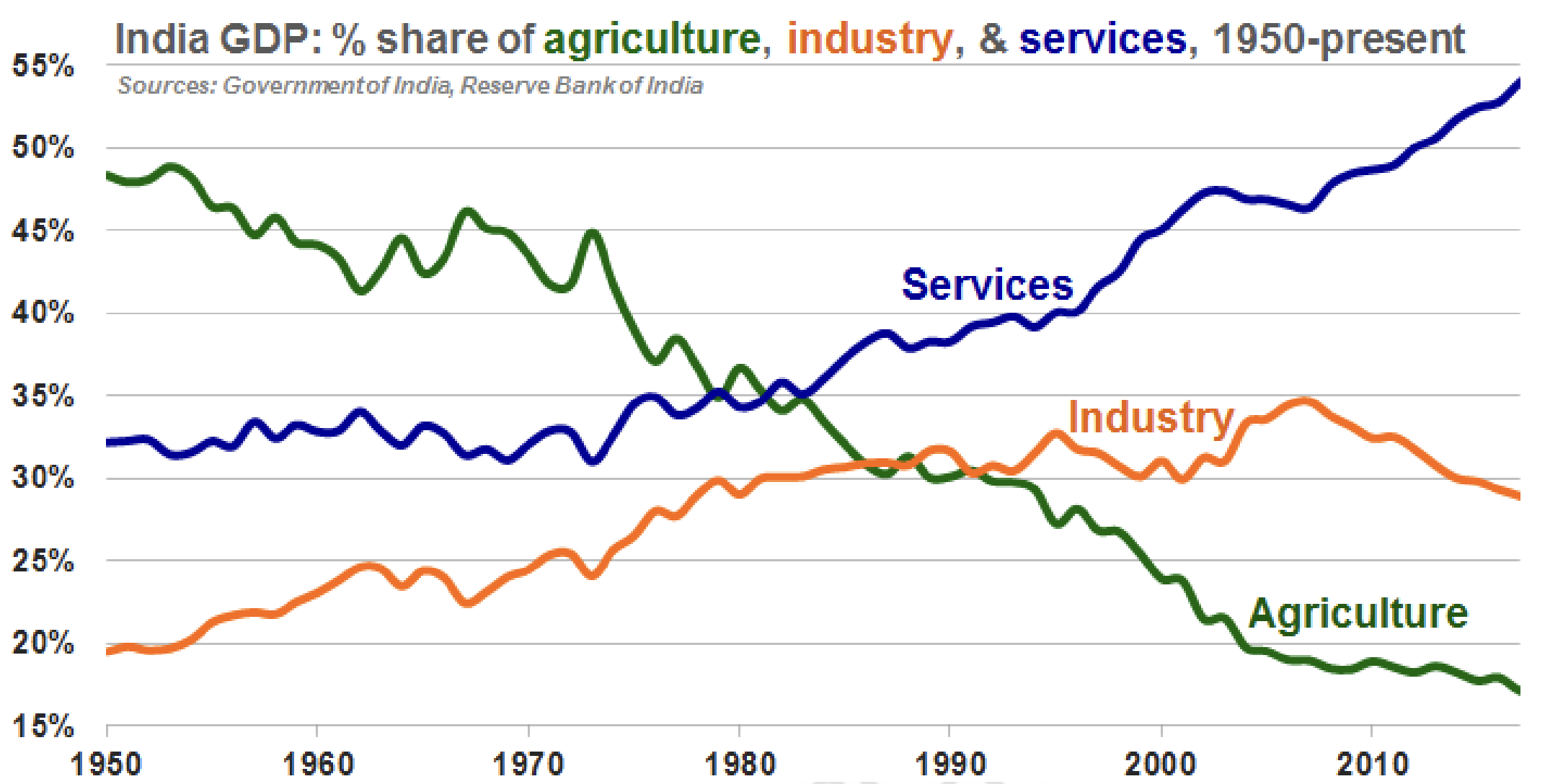

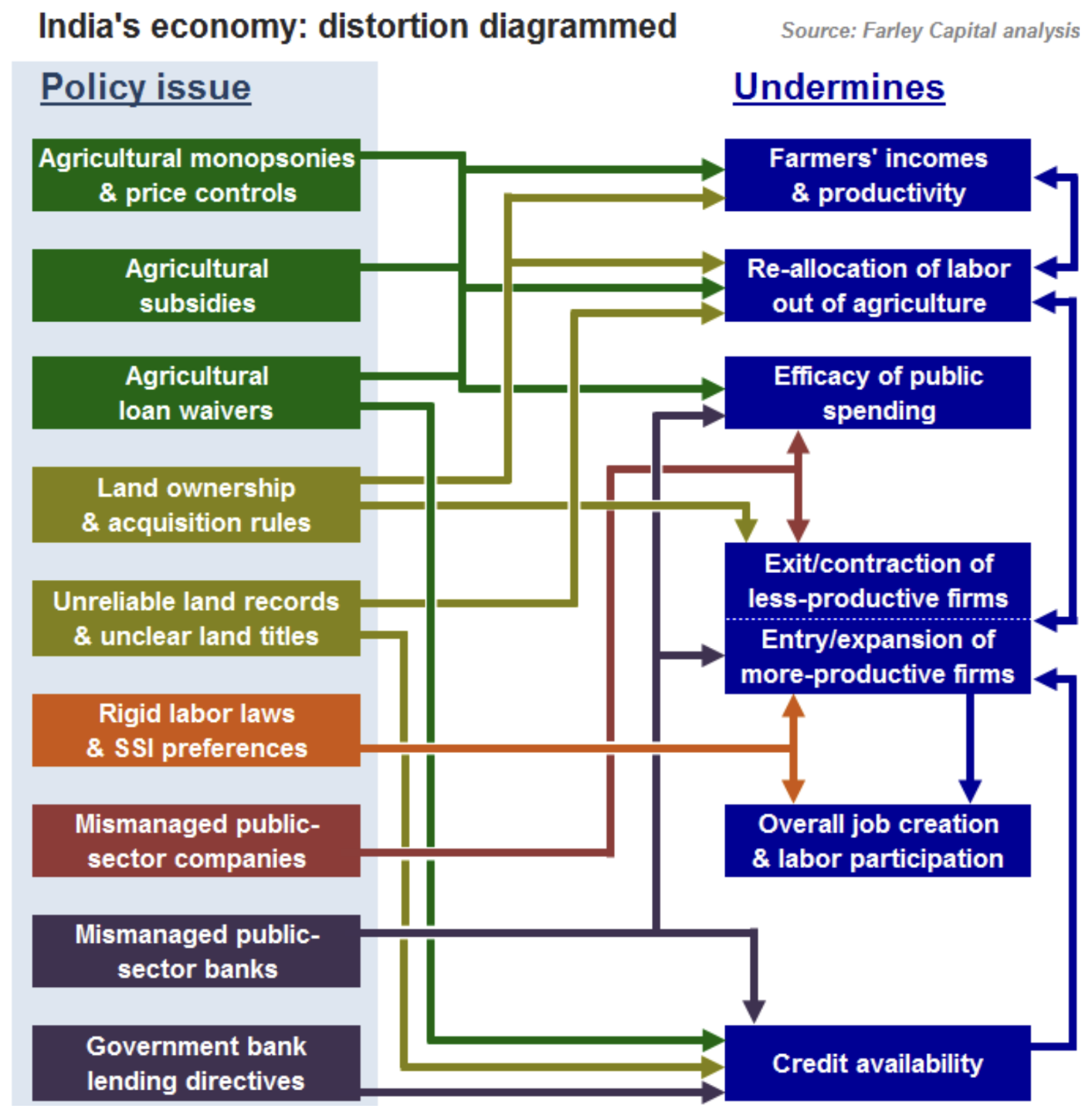

Consequently, markets for factors of production such as labor, land, and capital continue to be hamstrung by state intervention. The distorted allocation of these resources has dampened the growth of the sorts of labor-intensive enterprises that spearheaded the well-worn path to industrialization traveled by Europe, the United States, Japan, South Korea, and China. As a result, India’s development has sometimes appeared to be happening “back to front”, with a booming services sector contrasting with relative sluggishness in sectors dependent on tangible factors of production, such as manufacturing and agriculture.4

Sonia Gandhi (Rajiv Gandhi’s Italian-born widow) ultimately agreed to lead Congress in 1998, and runs the party to this day. Her son Rahul Gandhi headed Congress’s campaign in India’s 2014 general election, in which the party suffered its worst-ever historical defeat, losing to now-Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).5 The “first Indian politician to speak seriously of prosperity”, Modi is in many ways the polar opposite of India’s first prime minister (Jawaharlal Nehru) – who reportedly described profit as “a dirty word”.6

More recently, the momentum behind continued economic liberalization was bolstered by the results of India’s 2014 general election, in which Narendra Modi and his BJP party stormed to a landslide victory after campaigning on a business-friendly, pro-reform platform. The BJP won an outright majority in the Lok Sabha (lower house of Parliament) – a feat last achieved in 1984, and never before by a party other than Congress.7 To date, Modi has managed to implement a number of transformative reforms, from the removal of distortionary diesel subsidies to the introduction of a national sales tax that, for the first time, has given Indian businesses access to a single, unified market. Popular enthusiasm for Modi’s reformist government suggests that prior administrations may simply have been too timid in marketing the merits of further economic liberalization to voters.

Although the reforms unleashed by India’s 1991 crisis remain unfinished, there is little doubt that the decisions taken that year “have had a greater influence on the lives of [India’s] people (including the few hundred million born since) than any other political event in recent history.”8 Indeed, the fact that India has managed to achieve world-leading economic growth amidst the extensive distortions discussed below is a testament to the transformative impact of the post-1991 overhaul of the country’s economic policy.

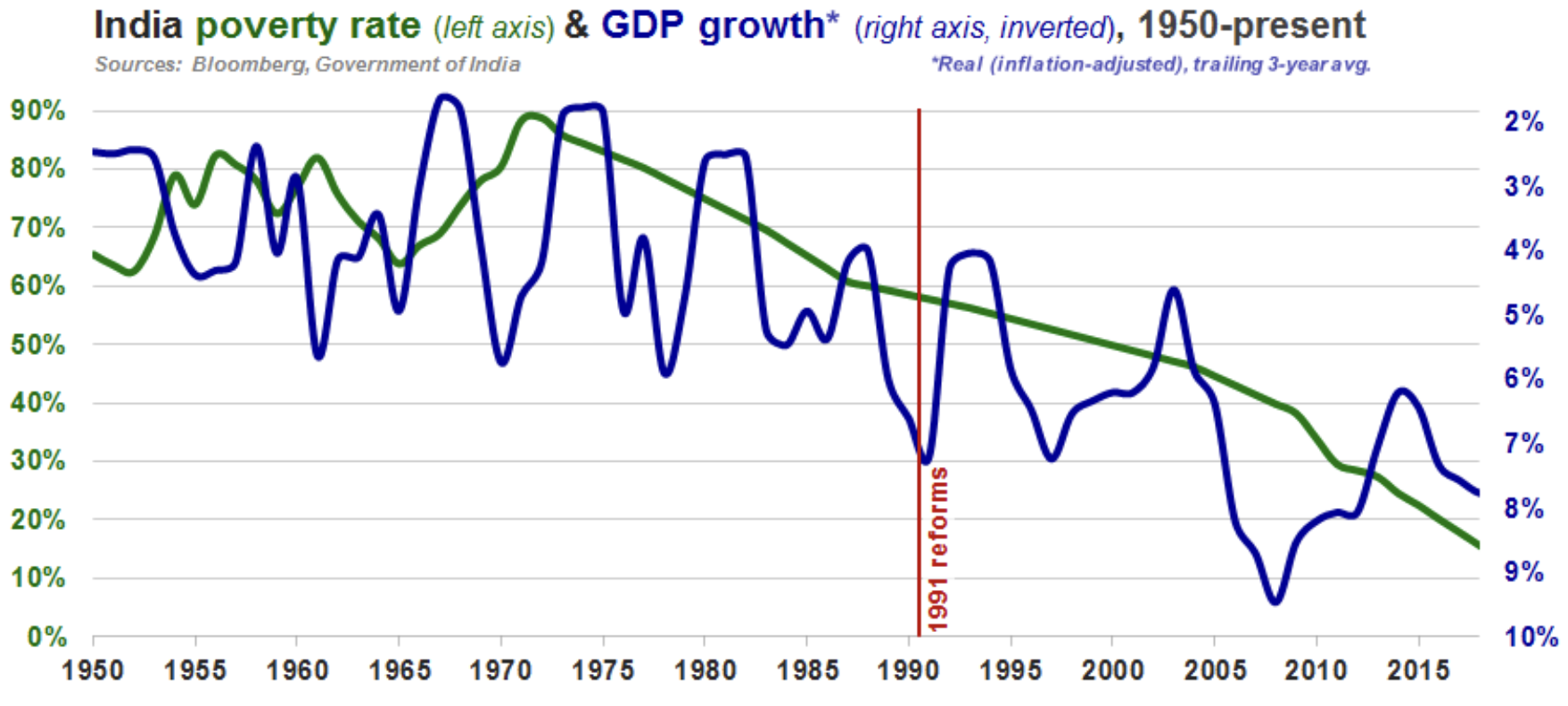

In the pre-liberalization era, it took India nearly forty years (from 1954 to 1991) to double per real (inflation-adjusted) per capita GDP. Since 1991, India’s real per capita income has doubled roughly every decade.10 Despite pre-liberalization governments’ barrage of “poverty alleviation” programs, India made little progress towards reducing poverty until the reform era. Following the acceleration in economic growth since 1991, the proportion of India’s population living in poverty has been cut in half.11

Today’s Indians – the majority of whom were not yet born in 1991 – cherish the immense variety of consumer goods, wide array of entertainment options, access to jobs with multinational companies, and opportunities for travel made available by their country’s liberalized, globalized economy.12 There is no constituency for a return to closed-off, bureaucratic socialism.13 Middle-class Indians “say their children laugh when told what it was like before 1991, when phones took years to get, soap burned your skin and red tape suffocated the economy.”4 As Montek Ahluwalia, one of Manmohan Singh’s deputies, stated in a recent interview, young people simply “cannot imagine the absurd level of controls that [had been] in place.”14

India has a realistic prospect of further accelerating its economy’s already- extraordinary growth, and of thereby expediting the rise out of poverty of hundreds of millions of people. Doing so will require completing the revolution that began a quarter-century ago, by implementing productivity-enhancing reforms to the areas that have limited the extent of India’s post-1991 economic boom.

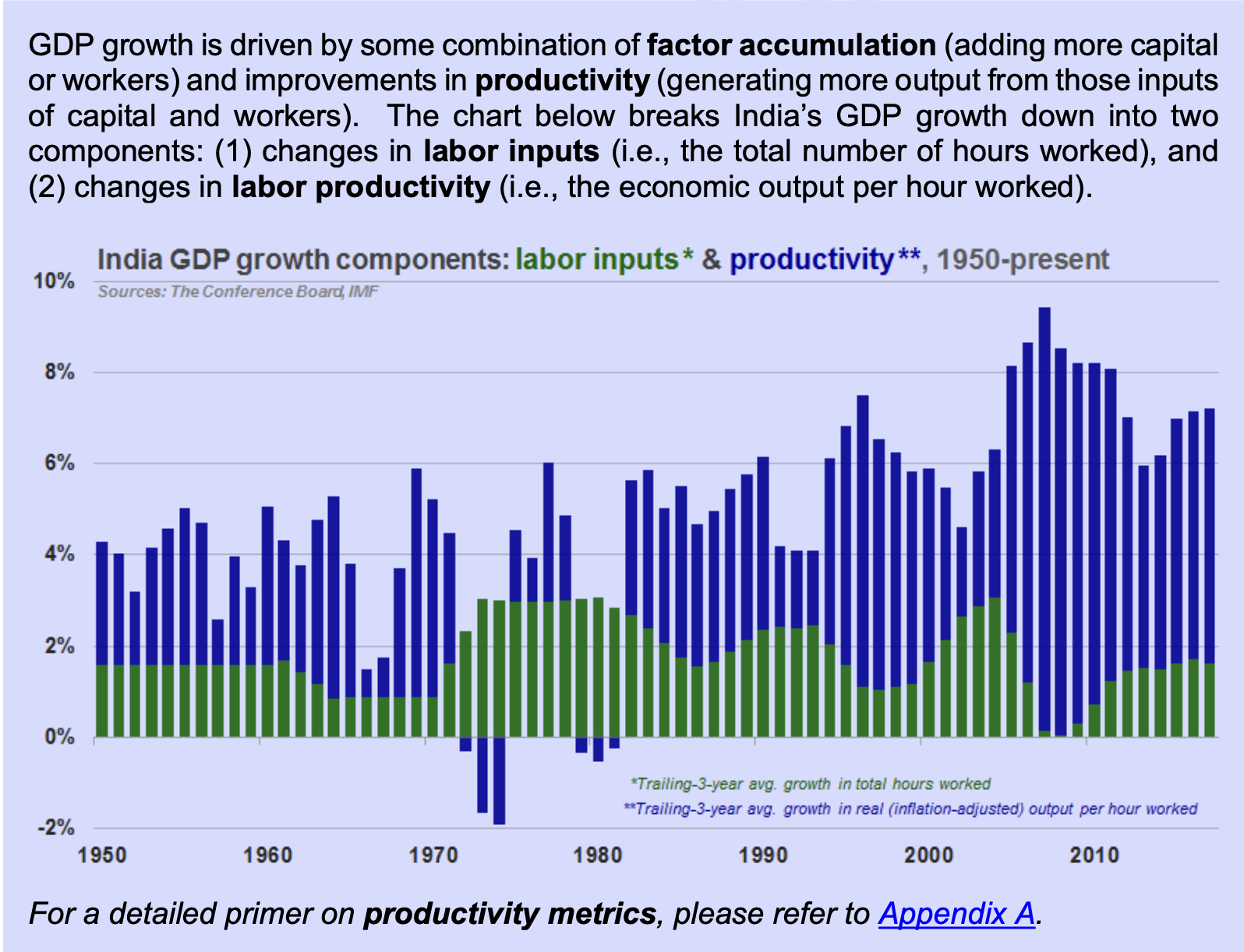

Improvement in India’s labor productivity has been and will almost certainly remain the single most important driver of the country’s GDP growth. Boosting labor productivity entails some combination of enhancing the productivity of existing jobs, trimming the number of low-productivity jobs, and creating new high-productivity jobs.15 By contrast, India’s current approach to the areas discussed below curtails productivity by undermining farmers’ ability to earn a livelihood, slowing the shift of workers from agriculture to higher-productivity sectors, hindering enterprises’ ability to acquire land, limiting the number of highly-productive companies, stranding resources within unviable firms, and proactively funneling scarce capital to sub-optimal uses.

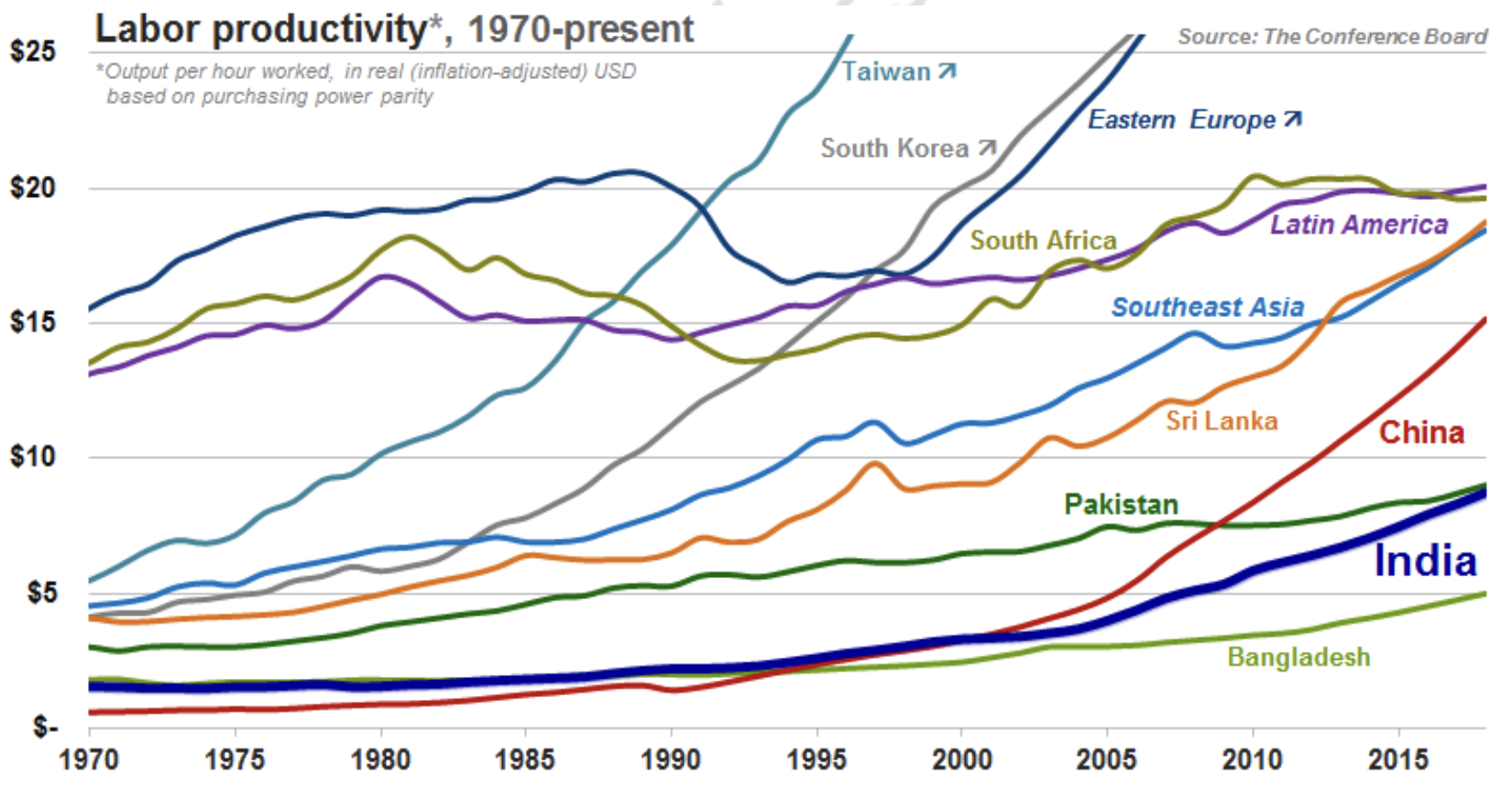

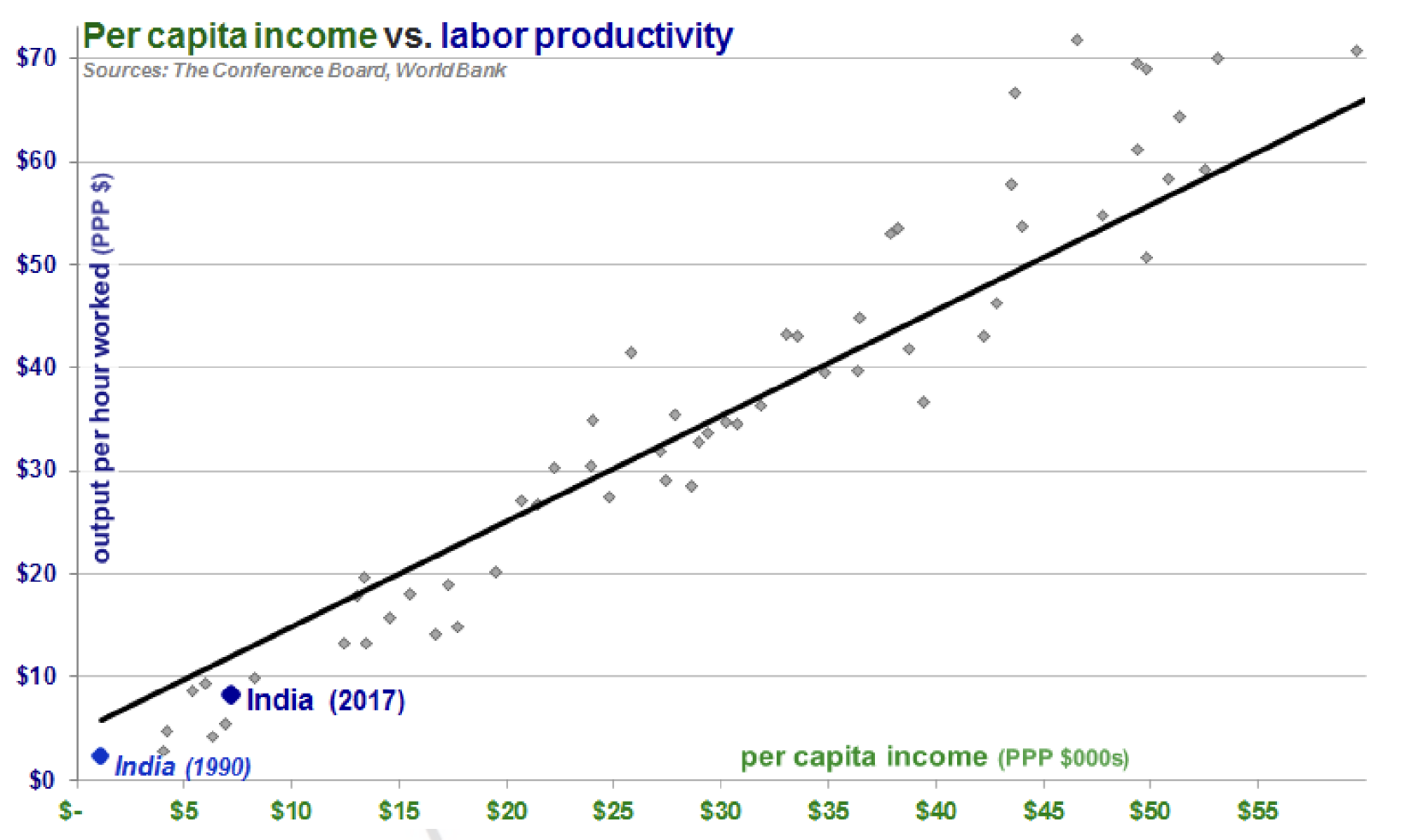

As recently as 2002, Indian workers’ labor productivity matched that of China. While India’s productivity has increased since then at a compound annual rate of 6%, the approximately $8 worth of GDP per hour now generated by the average Indian worker equals just half the analogous statistic for China.16 India’s performance has lagged in large part due to a web of interrelated legal restrictions, market distortions, and counter-productive incentives that have warped the Indian economy’s allocation of resources and stifled the potential of the country’s workers and businesses.

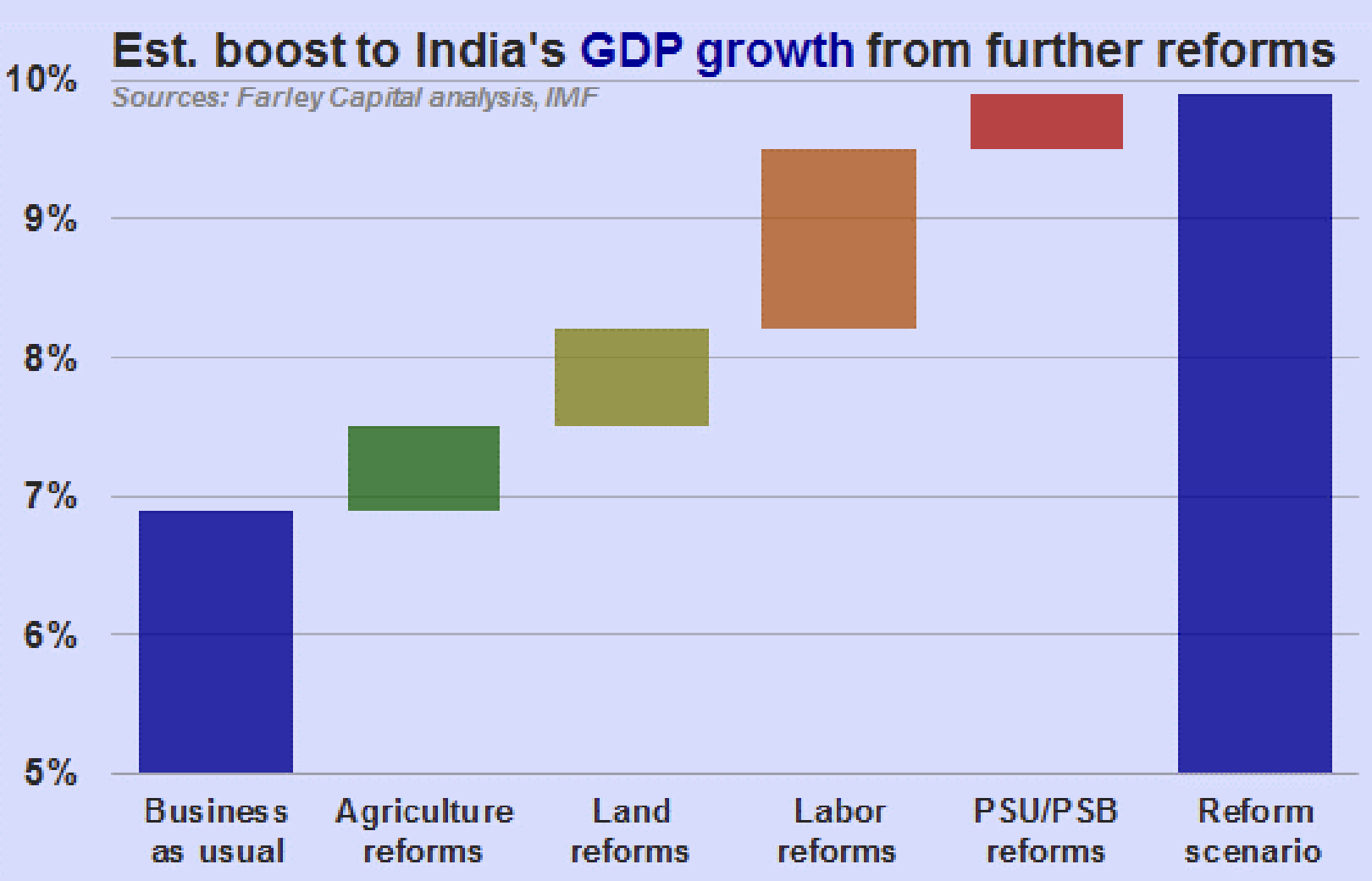

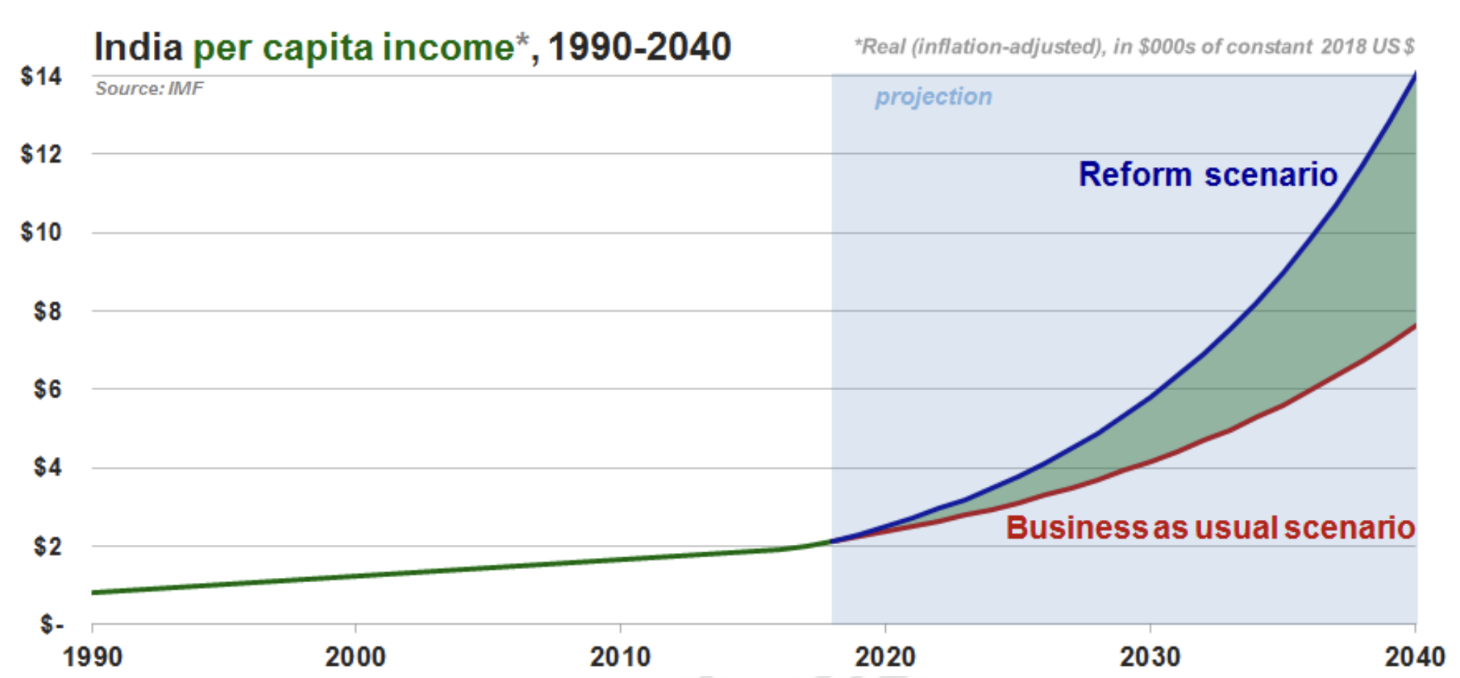

We estimate that addressing the economic deficiencies discussed below could boost India’s annual GDP growth rate by 3 percentage points, relative to a “business as usual” baseline (see Appendix B for a discussion of the methodology used to calculate this number).

Agriculture

With regulation of agriculture constitutionally delegated to the individual states, the sector was almost entirely bypassed by India’s post-1991 liberalization.17 Today, Indian agriculture remains stuck in a “time warp” of statist, productivity-sapping restrictions that hobble farming households’ ability to support themselves while, simultaneously, impeding their ability to shift into less-menial, more-productive work.18

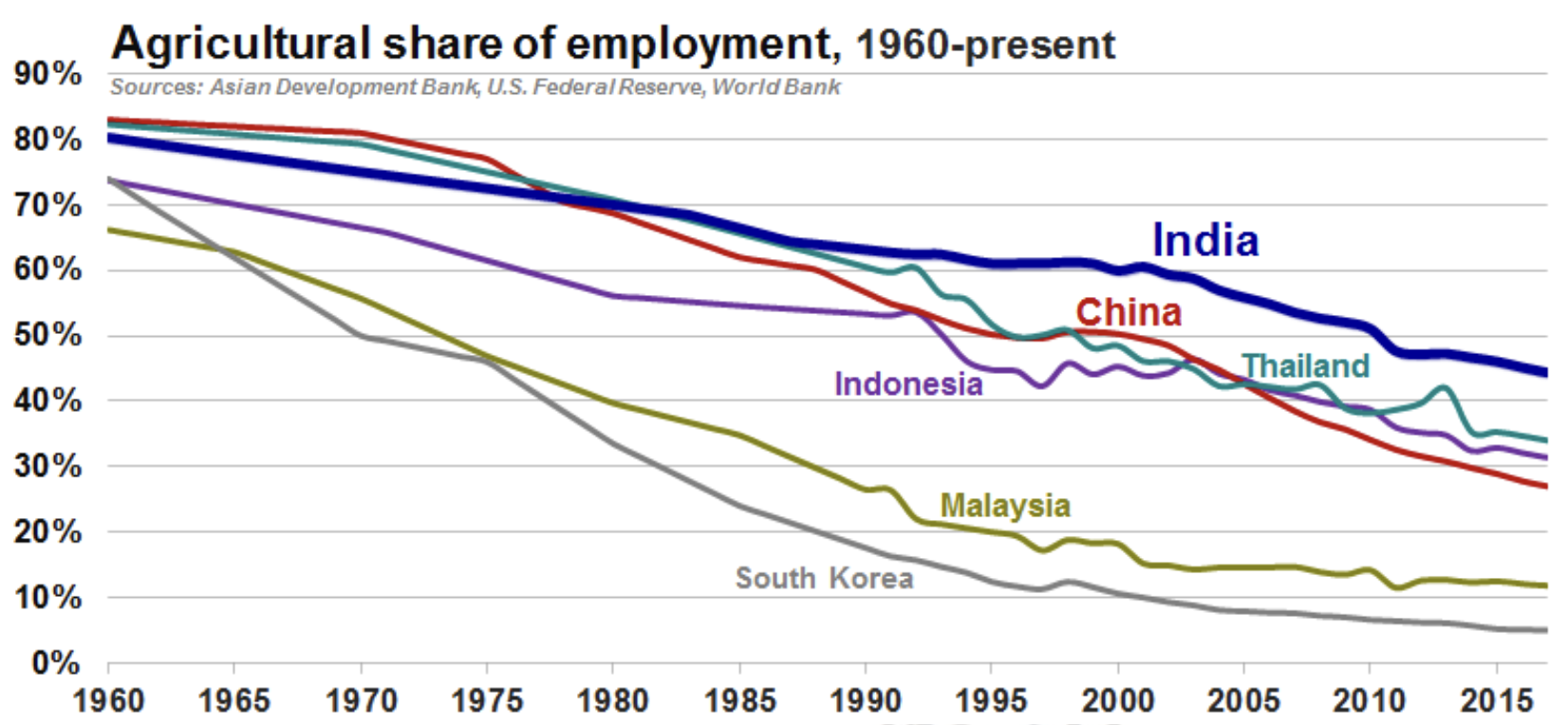

The result has been a double whammy for the economy’s productivity. As recently as the 1980s, the share of workers employed in agriculture was roughly identical in India, China, and Thailand. Since then, India has re-allocated workers from agriculture to higher-productivity sectors at a significantly slower pace than the latter two countries.19 Meanwhile, sluggish productivity growth within agriculture means that although roughly half of all Indian workers still earn their livelihood from food production, they contribute just 17% of the country’s GDP.20

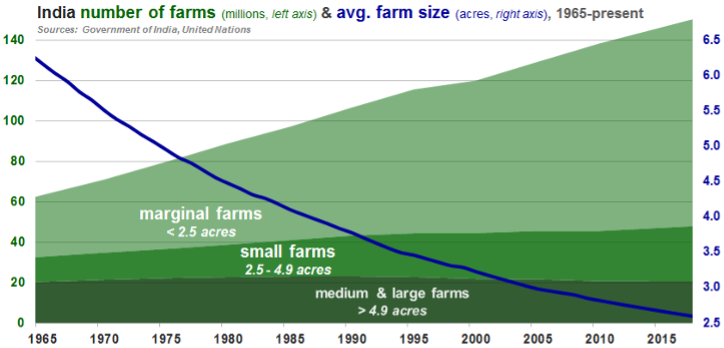

Indian states’ “land ceiling” laws and related constraints on the ownership, sale, and leasing of agricultural property (detailed in the following section) have, in combination with inheritance rules, effectively trapped the country’s farmers on ever-shrinking, less-productive parcels of land. Over the past several decades, the size of the average Indian farm has halved, to just 2.6 acres; most of the country’s farmers till plots smaller than 2 acres.21

This fragmentation has constrained farmers’ ability to invest in productivity-enhancing improvements.22 Less than 40% of India’s agricultural land is irrigated, leaving most farmers dependent on unpredictable monsoon rains and costly fertilizers.23 A majority of farming operations are still conducted using human and animal labor, without the aid of tractors or other mechanical equipment.24 As a result, the country’s rates of production per harvested acre of rice, wheat, cotton, and every other major crop significantly trail global averages; India’s rice yields lag those of its neighbors Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.25

Even in years when monsoon rains arrive on schedule, Indian farmers see their incomes squeezed “like ripe mangoes” by government policies and public-sector middlemen that distort the production, distribution, and pricing of agricultural produce and inputs.26 In most states, farmers must deliver their harvests of wheat, rice, fruits, vegetables, and other key crops to a mandi (market yard) operated by a government Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee (APMC).27

Originally intended to serve the interests of farmers, India’s 7,000-odd APMC markets are in practice often dominated by cartels of agents, traders, and local politicians who extract hefty commissions and fees, while colluding to limit the wholesale prices received by producers. Farmers for whom it would be uneconomical to bring their harvest to a distant state-run market are forced to rely on yet another layer of middlemen. In all, an average of five to six such intermediaries between agricultural suppliers and consumers ensure that Indian farmers receive less than 25% of the retail price for their crop.28

By preventing agricultural producers from selling directly to the private sector, the state APMC monopolies have deterred the establishment of decentralized procurement networks that would be forced to compete for farmers’ business on the basis of transparent, market-driven prices. As a result of the APMC system’s barriers to interstate supply chains, Delhi grocery shoppers often find it easier to buy a California apple than one grown in a nearby state. By contrast, agricultural markets not shackled by the APMC system, such as milk and dairy products, feature competitive procurement networks that pay farmers over two-thirds of their commodities’ retail value.30 States that have even partially relaxed their APMC rules (e.g., Maharashtra, which in 2016 exempted fruits and vegetables from the law) have subsequently reported substantial boosts to their farmers’ incomes.31

Like the old License Raj, the APMC system is part of a vicious cycle of production-inhibiting policies – each one enacted in a misguided attempt to counteract the scarcities and distortions wrought by the others. Denied access to market-driven prices, farmers have over the years demanded that the government set ever-higher minimum support prices (MSPs).32 MSPs theoretically represent floor prices for wheat, rice, cotton, and 20 other crops, which states are expected to guarantee by being prepared to purchase, at the MSP, any eligible produce delivered to an APMC mandi. In practice, after subtracting commissions extracted by middlemen, farmers often receive much less than the official MSP for their crop.27

Similarly, the government’s costly subsidies for agricultural inputs such as fertilizer, energy, and water largely fail to reach the neediest farmers. Fertilizer subsidies alone account for over ₹700 billion ($11 billion) annually, about 0.6% of GDP.33 Fertilizer companies receive these directly, as compensation for selling their end-product at government-set prices. Because this reimbursement is calculated on a cost-plus basis, suppliers have little incentive to enhance productivity. Because the subsidy is both inefficiently distributed and very generous, most subsidized fertilizer is diverted either to the richest farmers, or to a black market where smaller farmers pay 60% higher prices, on average.34

At the same time, subsidies for agricultural inputs stoke unintended effects that undermine the effectiveness of those same inputs. Below-market prices drive farmers to over-utilize fertilizer (particularly the urea-based kind, due to the strength of the urea manufacturers’ lobby),35 thereby degrading their soil and forcing them to use ever-increasing quantities of inputs just to keep productivity stable.36 Meanwhile, the government supplies electricity and water at a fraction of their cost of production. Making these inputs “almost free” to farmers has given them an incentive to over-produce thirsty crops such as rice and sugarcane, contributing to unsustainable declines in India’s groundwater levels.37

Another law, the 1955 Essential Commodities Act (ESA), empowers India’s central and state governments to impose price controls and arbitrary caps on stockpiles of food crops and other “essential” commodities. Intended to protect consumers against “irrational” price spikes caused by speculative hoarding, the ESA dampens farmers’ incentive to increase production in response to genuine shortages (e.g., weather-related disruptions).38 Moreover, the law deters investment in cold storage facilities, food processing plants, and other infrastructure that could help smooth out fluctuations in the supply of seasonal crops. As a result, fully one-third of India’s farm harvest spoils each year for lack of storage and supply chain capacity.39

To top it all off, authorities have for years attempted to placate farmers via financial directives and concessions (see the banking system section for more details). Banks are required to allocate roughly one-fifth of all lending to agriculture, at below-market interest rates. Additionally, the country’s central and state governments periodically enact agricultural loan waivers.40 Among Indian politicians’ favorite tools for rallying rural support, these waivers involve the state assuming farmers’ debts, typically in the run-up to an election.

Over the past decade, India’s central and state governments waived over ₹2.1 trillion ($32 billion) in agricultural loans41 – enough to have financed the irrigation of over half of the country’s monsoon-dependent farmland.42 These bailouts encourage farmers to take out more loans, and (in the expectation of yet another waiver) to not repay them even when they are able to. Waivers penalize borrowers who honor their loan commitments, while failing to assist the poorest farmers (who lack access to formal bank loans).43 Consequently, the government’s various handouts have actually entrenched farmers’ financial vulnerability. Over half of India’s agricultural households are indebted, many to informal moneylenders whose steep interest rates trap farmers in hard-to-escape cycles of debt.44

When the various policies discussed above were originally enacted in the 1950s and 1960s, they were seen as essential for safeguarding India’s food security and improving farmers’ livelihoods. In practice, these restrictions have impeded the consolidation of splintered croplands and pastures into larger, more efficient plots, while exposing farmers to exploitation by intermediaries and leaving many mired in debt. The government attempts to keep staple foods and inputs affordable using tools, such as MSPs and subsidies, which cushion farmers’ incomes – at the cost of dampening their incentive to boost supply through better productivity, or to seek employment outside of the agricultural sector.45 Policies such as loan waivers and stockpile limits merely address symptoms of the problem, while ignoring the root cause of the market’s dysfunction – namely, that the agricultural sector is increasingly unable to productively employ India’s expanding rural labor force.46

The government appears to be taking tentative steps towards reform, including replacing subsidies paid to producers of agricultural inputs with direct transfers into farmers’ bank accounts.47 In April 2017, the national Ministry of Agriculture began encouraging states to adopt a new model law that would abolish APMC monopolies, cap commissions and fees payable by farmers, establish electronic market platforms, and ease barriers to interstate trade in farm produce.48

A more comprehensive overhaul of the current system would allow India, already a net exporter of food (having been one since the 1990s), to produce even more food using less land area.49 India would benefit from re-directing public agriculture spending, over 90% of which is currently channeled into subsidies and price supports, into irrigating and mechanizing a smaller number of larger farms.17 Instead of relying on MSPs and subsidies to shore up agricultural incomes, India could give farmers access to competitive markets, crop insurance, and agricultural futures – allowing them to lock in profitable prices before they plant a crop.50

Land

India’s land market is essentially paralyzed, with a vast and costly gap between supply and demand that damages the interests of both current landowners and potential land buyers. The share of India’s land dedicated to food production (60%) has remained static for the past half-century,52 even though two-fifths of the country’s farmers say they would like to sell their land and move out of agriculture.53 At the same time, industrial and infrastructure projects worth hundreds of billions of dollars have stalled for lack of land-related or regulatory clearances.54

Part of the problem relates to the sheer population density of India, where property holdings tend to be highly fragmented – particularly among the half of the population that remains dependent on agriculture (the subject of the preceding section). However, these issues are rooted in and exacerbated by failures of governance (e.g., poorly-maintained land records) and onerous laws that limit the amount of land a single family can own, prohibit farmers from selling their acreage directly to industrial firms, and impose steep duties and fees on property transactions.55 Because India’s Constitution gives regulatory power over land to both the central and state governments, various reforms enacted in Delhi following the 1991 crisis have done little to ease these legal obstructions.

It was not until 1999 that the national authorities allowed India’s state governments to repeal regulations implementing the 1976 Urban Land Ceiling and Regulation Act (ULCRA). With the aim of enhancing the availability of affordable housing, ULCRA capped the amount of vacant land that could be owned by any individual or company at 500 square meters (approximately 5,400 square feet) in the largest cities, and up to 2,000 square meters (roughly 21,500 square feet) in smaller towns. Holders of excess vacant land were forced to sell it to the government for a nominal price.56

In practice, ULCRA aggravated the problems it set out to solve, as landowners resorted to protracted litigation or outright bribery to avoid selling their property to the government for a fraction of its fair value. In addition to creating a severe shortage of urban land, the law also served as a barrier to the exit of unprofitable “zombie” firms, many of which were prohibited by ULCRA from selling their most valuable asset for anything close to its market price. Compared to states that dragged their feet on revoking the law, states that scrapped ULCRA early on experienced faster urban population growth,57 as well as more rapid improvement in labor productivity.58

While ULCRA has been abolished in the majority of India’s states, similar controls remain in effect in rural areas throughout the country. Most states enforce “land ceiling” laws that cap at as little as 10 acres the amount of farmland that can be owned by a single household, prohibit the sale of agricultural land to non-farmers, and tightly restrict landowners’ ability to even lease out rural property.59 In combination with the country’s inheritance laws (which provide for the equal division of property among children), these curbs have driven the fragmentation of agricultural holdings into ever-smaller, less-efficient farms, while limiting the amount of land available for industrial and infrastructural development.53 Today, the average Indian farmer tills a plot of 2.6 acres, compared to 440 acres in the United States60 – meaning that a company seeking to acquire a 500-acre parcel could find itself negotiating with hundreds of families.61

India’s market for land is further undermined by the country’s poorly-maintained, imprecise land records. Under Indian law, the onus of proving ownership is on the purchaser of a property – a task that generally entails producing a chain of documents linking back to its past owners (the latest sale deed is not enough to guarantee title).62 As no comprehensive survey of India’s land has been conducted since the time of the British Raj, this process often necessitates reconciling discrepancies between an array of paper deeds, property tax receipts, and maps gathered from the archives of multiple autonomous, uncoordinated municipal authorities.63

Due to the absence of transparent, centralized land records, buyers do not have recourse to title insurance – the system used in the U.S. and other developed countries, whereby private companies insure against losses resulting from title defects (e.g., errors in public records, unknown liens, missing heirs, et cetera).64 While a national land record modernization program has been underway since 2008, its progress has been hindered by the difficulty of consolidating and digitizing conflicting, incomplete legacy records – including some (e.g., rural boundary lines established by unrecorded verbal agreements) that have no paper trail at all. Unsurprisingly, land- and property-related disputes account for two-thirds of all civil litigation in India.63

To avoid the risks involved in negotiating with and corroborating the property titles of multiple property-owners, Indian companies frequently rely on state governments to acquire land on their behalf, using their power of eminent domain. Until recently, the process by which authorities were able to exercise that power was governed by the colonial-era Land Acquisition Act of 1894, which allowed for the forcible acquisition of land, at a government determined price, for any “public purpose”. That broadly-defined term came to encompass property subsequently handed over to private firms, contributing to animosity among rural landowners – many of whom concluded that they were being fleeced by corrupt state officials acting in collusion with private developers.65

In 2013, the 1894 land law was replaced by new legislation, the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act (LARR), that somehow managed to make things worse. Passed by the then Congress-led administration, the LARR obligates authorities to submit detailed social impact assessments, hold public hearings, and pay for the “rehabilitation and resettlement” of all displaced parties (including not only property owners, but also other affected people, e.g., farmhands and their families). The latter obligation is in addition to the compensation of up to four times market value payable to the owners of acquired land. The requirements are more complex in the case of land intended for private projects (including public-private infrastructure partnerships), which must obtain the prior consent of at least 70% of affected families before even initiating the process of property acquisition.61

The fraught politics of acquiring land in India are epitomized by Tata Motors’ stymied attempt to build a new assembly plant in Singur, West Bengal. In 2006, Tata announced plans to build the facility on 1,000 acres of rural property procured on its behalf, via eminent domain, by the state government. Within two years, however, violent protests by displaced farmers and opposition politicians prompted Tata to re-locate the project.66 In 2010, the company’s factory was finally commissioned on a site 1,200 miles to the west, in Sanand, Gujarat – reportedly selected after the latter state’s then-leader Narendra Modi (now India’s prime minister) sent Tata’s chairman a text message saying “welcome”.67

The LARR’s convoluted provisions have exacerbated the mismatch between supply and demand, further stifling the economy’s potential. On average, it takes nearly five years to acquire a piece of property under the law.68 By imposing daunting permission conditions while leaving unresolved the ownership ambiguities and land ceiling laws at the root of India’s highly distorted land market, the LARR damages the interests of both potential land buyers as well as existing landowners. Repeated attempts by the Modi government to loosen some of the legislation’s more onerous requirements have been stymied by opposition parties, who have portrayed proposed changes as “anti poor”. In fact, while the LARR’s safeguards are intended to protect vulnerable communities from abuse by powerful interests, the law fails to address the crucial process for proving land ownership – the high cost of which is often prohibitive for the poorest Indians.69

Reforms leading to a more functional land market would reduce the need to use eminent domain in the first place. Giving landowners clear title to their property, abolishing caps on landholdings, and allowing farmers to sell their land to the highest bidder would allow land to trade at mutually-beneficial, market-clearing prices. Every Indian state would benefit from following the lead of Rajasthan, which in 2016 established an independent authority to verify and guarantee land titles.71 Meanwhile, Andhra Pradesh is demonstrating the merits of “land pooling”, an emerging alternative means of property acquisition in which landowners voluntarily hand over their land to a government agency in exchange for a share of the higher-value developed land.72 Via a pooling initiative, Andhra Pradesh’s government has acquired over 30,000 acres around the village of Amaravati – site of the state’s new capital, a planned city the size of Seattle.73

The opportunity costs of failing to act are significant. The paralysis in India’s land market is so extreme that smaller, less-efficient firms have better access to land than larger, more-productive companies.74 Because land is the least flexible factor of production, its misallocation tends to distort the distribution of everything else, as well. For example, manufacturers unable to secure property adjacent to existing population centers are relegated to subpar locations with scarcer labor, costlier electricity, and trickier logistics. Given land’s function as a common form of loan collateral, businesses’ lack of access to land will also tend to limit their access to capital.75 Studies examining land’s role in various countries’ economic development suggest that reforms facilitating the more efficient allocation of this crucial factor of production are associated with a roughly 20% increase in output per worker.58

Labor

Widespread distortions to India’s labor market undermine the country’s economic potential in three ways: (1) by dampening growth in overall employment, (2) by limiting the number of highly-productive, big firms, and (3) by slowing the shift of workers from agriculture to higher-productivity sectors. The misallocation of this factor of production explains why labor-intensive industry has not played a greater role in the development of an economy with such extraordinarily competitive labor costs – as well as why the most successful Indian manufacturers have tended to emerge in businesses, such as pharmaceuticals and chemicals, that are relatively skill- and capital-intensive, rather than labor-intensive.17

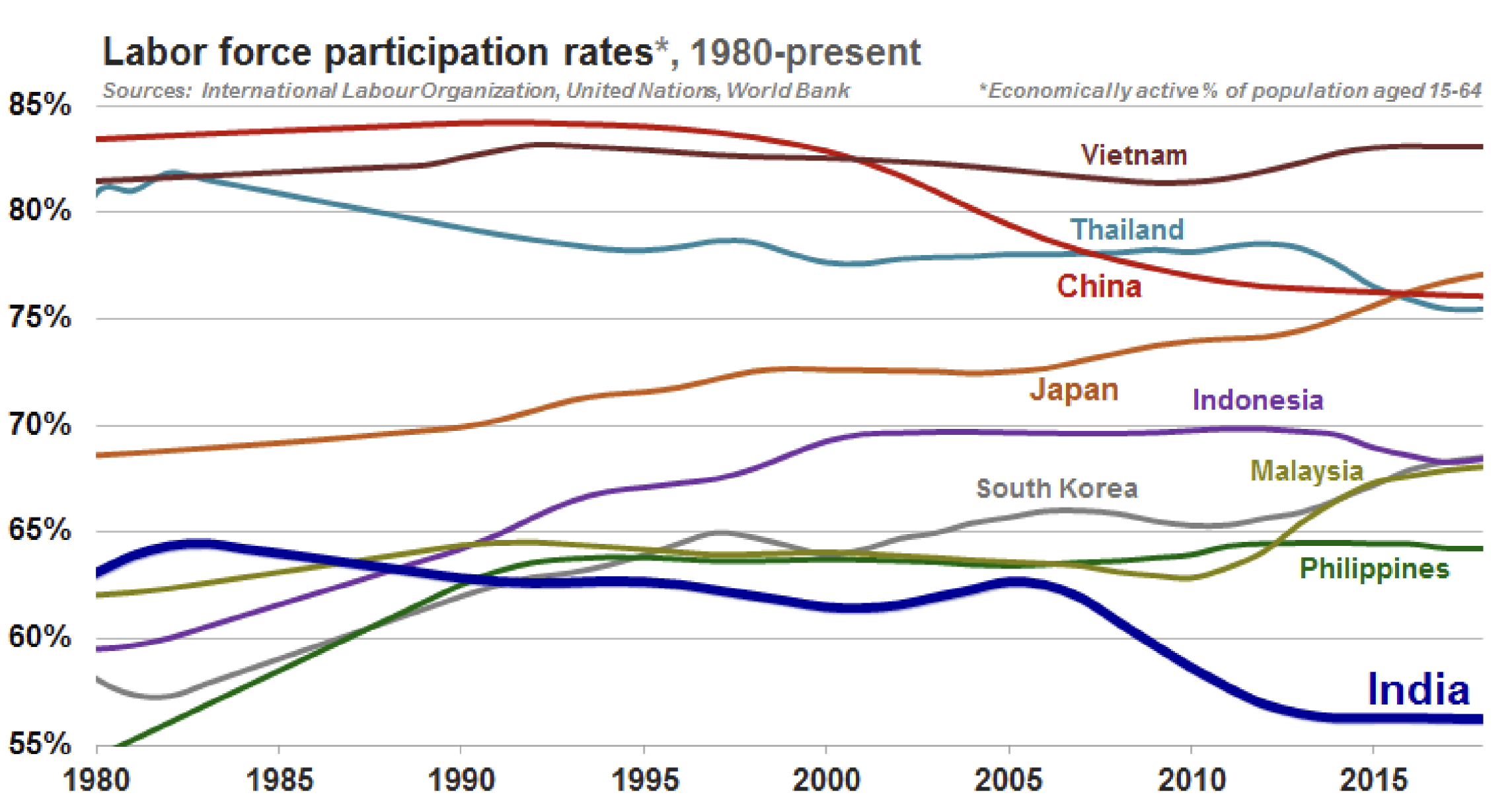

India’s post-1991 reforms largely left untouched the country’s overly rigid, anti-competitive labor laws.76 As a result, “even when India’s companies grow, they aren’t taking its workforce along.”77 From 1991 to 2017, India’s working age (i.e., aged 15 to 64) population expanded by 14 million annually, to nearly 900 million people. Over the same period, both the number of jobs and the labor force (i.e., the number of people employed or seeking a job) increased by less than 7 million each year, to roughly 500 million.78 Consequently, India’s labor force participation rate (the country’s labor force divided by its working-age population) has declined to the lowest among major Asian economies.79

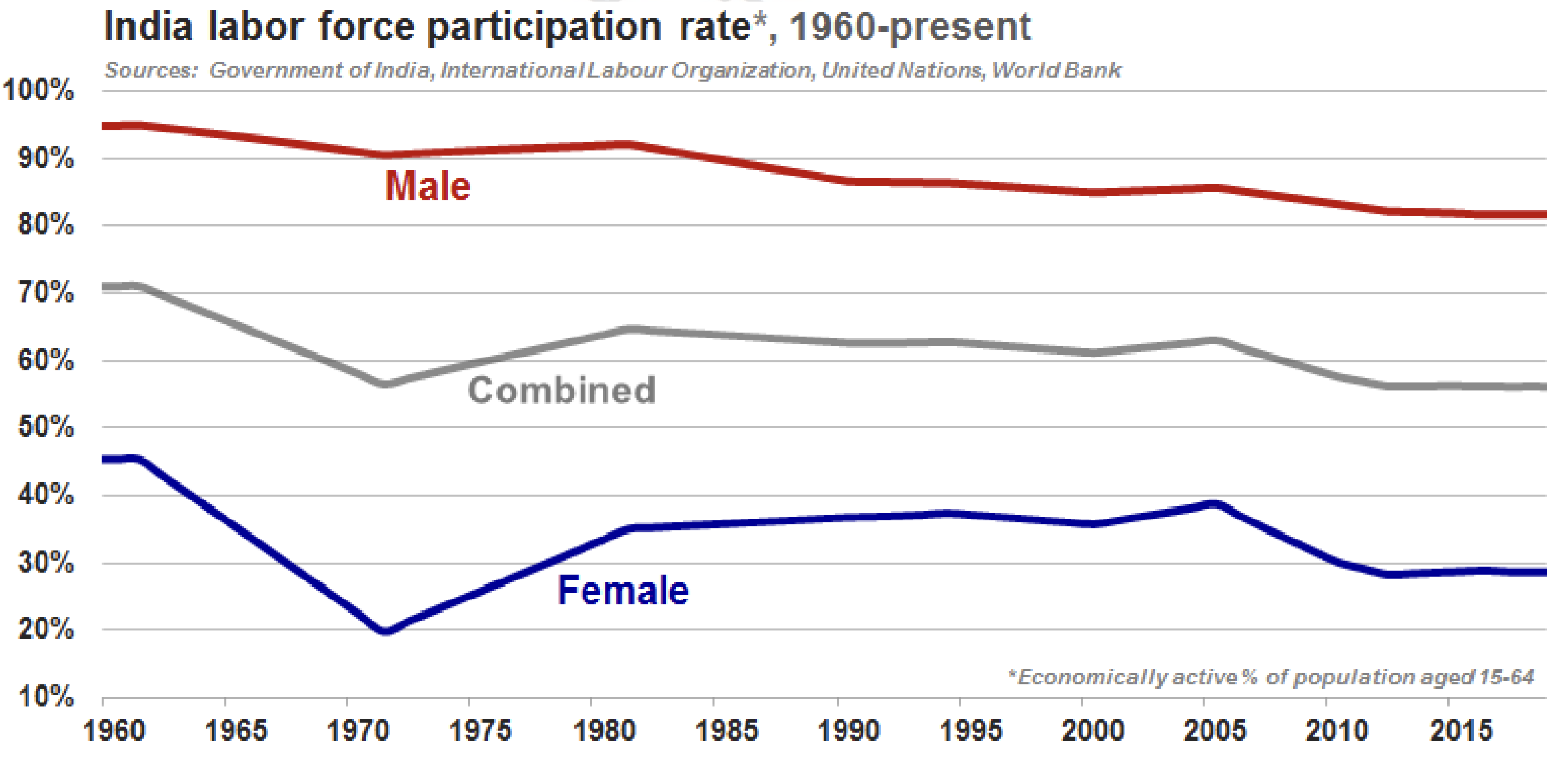

Part of the decline in India’s labor force participation rate has been driven by the increasing number of young people choosing to remain in the education system rather than enter the labor force at the age of 15. However, the primary factor has been a simple lack of employment opportunities, combined with a gap between available workers’ skill-sets and the demands of companies.80 In a nutshell, while expanding employment in the service sector (and, to a lesser extent, in the industrial sector) has more than offset declines in farm jobs, it has failed to keep up with growth in India’s working-age population.81 In response, millions have left the labor force altogether. The impact has been particularly acute among India’s working-age women, barely one-quarter of whom work – compared to over two-thirds of their counterparts in China, Thailand, and Vietnam.82

Over the past quarter-century, India has generated tens of millions of well-paying jobs in information technology and other service sector industries. However, such jobs account for a small fraction of the country’s overall workforce. India’s economy has been less successful at creating formal jobs for lower-skilled workers in large part due to the country’s overbearing labor policies. Enacted with the aims of promoting employment and protecting workers, these rules have in practice deterred new entrants and discouraged existing companies from drawing upon the country’s bountiful supply of lower-skilled labor. Instead, they have incentivized firms to hire a few highly-skilled employees and invest in automation.17

For example, any establishment with 100 or more employees must abide by the 1947 Industrial Disputes Act, which makes it impossible to dismiss a single worker without permission from the state government.83 Manufacturers employing 10 or more workers remain subject to the 1948 Factories Act, which, among other outdated and oddly specific provisions, forbids spitting within the premises of a factory except into “spittoons [...,] a sufficient number” of which “[must] be provided [...] in convenient places” throughout the plant.84 Companies’ female employees face additional restrictions, including prohibitions on working night shifts.85

Until recently, Indian manufacturers also remained hamstrung by decades-old rules that “reserved” the manufacture of 836 labor-intensive products – including textiles, dyes, and agricultural machinery – for “small-scale industry” (SSI). These regulations effectively capped the output of reserved items by manufacturers once their investment in plant and machinery exceeded an arbitrary, periodically-adjusted limit (as of the 1990s, ₹6 million – equivalent to less than $200,000 at the then-prevailing exchange rate).86 The baffling logic of the SSI reservations was encapsulated by a 1980s comic strip showing India’s industry minister telling his staff, “We shouldn't encourage big industry – that is our policy, I know. But I say we shouldn't encourage small industries either. If we do, they are bound to become big.”87

Since 1997, the government has gradually loosened the SSI rules. Economic studies show that this has substantially boosted output, employment, and wages across previously-reserved industries.88 Furthermore, corporations are often able to skirt the restrictions imposed by the Industrial Disputes Act, Factories Act, and other still-active laws by splitting workers among smaller establishments and relying on contract labor. As a result, India’s large enterprises have been able to take advantage of the expanded access to productivity-enhancing technology, inputs, and capital afforded by the post-1991 liberalization of investment and trade, and are now roughly as productive as leading firms elsewhere in Asia.89

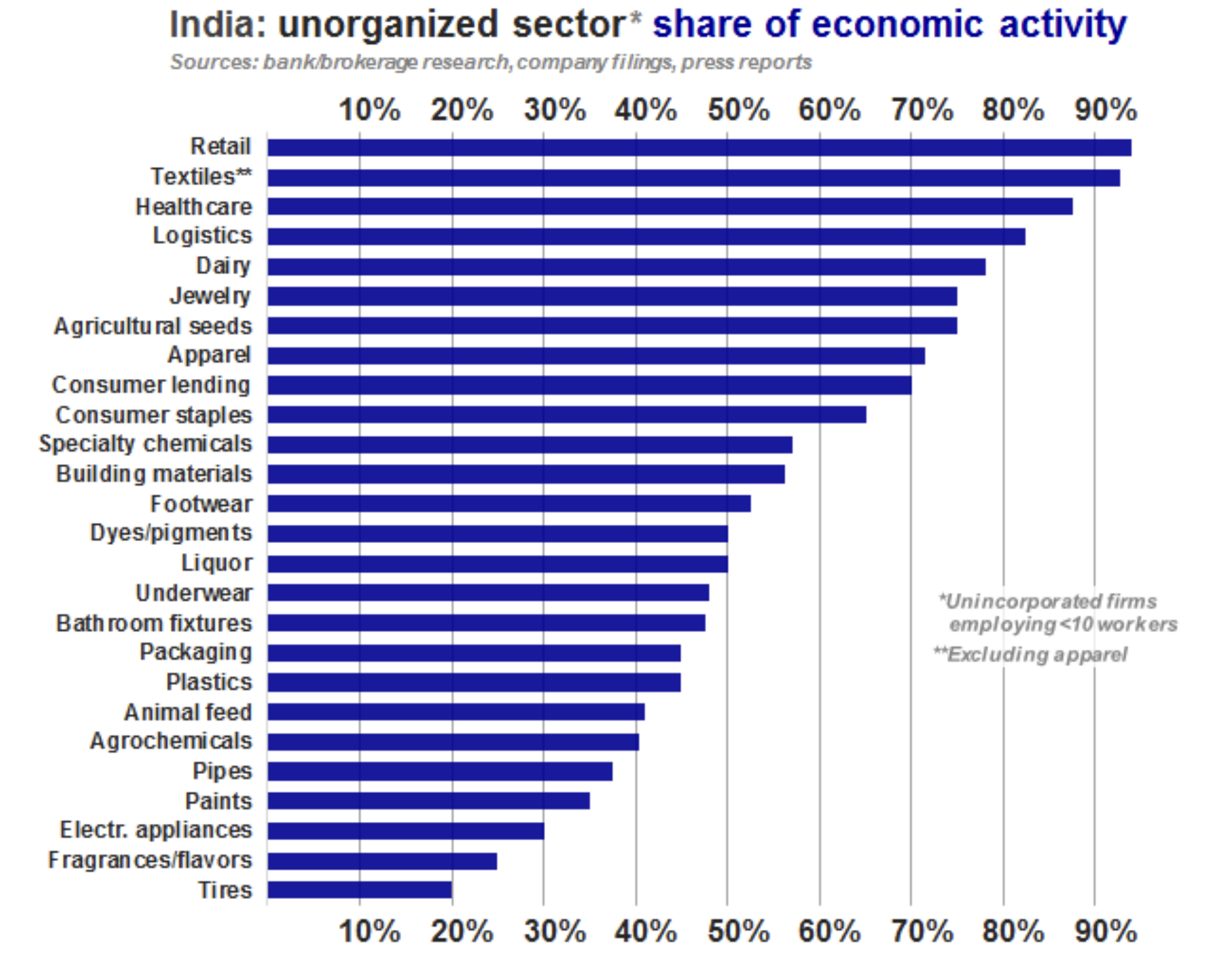

However, India’s onerous labor regulations have limited the number of these highly-productive, big firms. Instead, by making it harder for businesses to enter new markets, expand their capacity, or lay off workers, they have led to an overabundance of less-efficient, small firms. Less than one-fifth of Indian manufacturers employ over fifty workers, compared with three-quarters of their Chinese competitors.90 Companies in the “unorganized” sector (which comprises unincorporated enterprises with fewer than 10 employees) account for over half of output in industries including textiles, chemicals, building materials, and dairy products.91 Even in the booming service sector, large firms such as India’s well-known IT outsourcing giants account for only a small share of overall output and employment.92

As a result, the pace at which India has re-allocated labor from agriculture to higher-productivity sectors – especially manufacturing and industrial work – has been slow relative to China and other large developing countries. Since the 1980s, industry’s share of the Indian economy has barely budged. Recent decades’ significant decline in agriculture’s contribution to GDP has been driven entirely by the rising portion attributable to the service sector, which now accounts for over half of overall economic output.93 Manufacturing (the primary component of the industrial sector, alongside mining and the supply of electricity, gas, and water) accounts for just 17% of India’s GDP – compared to 30% of China’s.94

Despite India’s shortage of suitable jobs, nearly everyone who remains in the labor force finds work; the country’s unemployment rate has been stable at around 4% for decades.95 In the context of India – “where unemployment is not really an option” – a young person who fails to find a formal job would typically be put to work on the family farm, in a relative’s workshop, or in a neighborhood kirana (local convenience store). Informal positions such as these account for nine out of ten jobs in India.80 While they are included in labor market surveys’ measurements of employment, jobs in the informal economy (roughly synonymous with the “unorganized” sector) rarely offer much in the way of economic mobility.81

By preventing resources from flowing to more efficient uses, India’s labor restrictions have dampened growth in both overall employment and aggregate productivity. On average, the productivity of an unorganized sector worker is one-eleventh that of an Indian employed by a larger, organized enterprise. The differential is even wider in India’s manufacturing sector, where firms in the most-productive decile are 22 times more productive than firms in the bottom decile; the comparable ratio in the U.S. is only 9 to 1.15 Decades of cross-country data show that liberalizing reforms lead to job losses as less-productive firms contract or go out of business. However, by opening up space for the expansion or entry of more-innovative firms with greater economies of scale and/or superior access to technology, capital, and global supply chains, the net impact on employment is positive.50 By bringing the dispersion in productivity between its industrial firms down to U.S. levels, economic studies predict India could boost the sector’s overall productivity by at least 40%.96

Seeing the lack of modern employment opportunities generated by India’s economy, the hundreds of millions of Indians who continue to toil in insecure, unorganized sector jobs can “look at the hype surrounding the [post-1991 reforms] and wonder what was in it for them.”77 To avoid jobless growth, India will need to simultaneously increase its attractiveness to employers of less-skilled workers (e.g., labor-intensive manufacturers) and improve the effectiveness of schools and training programs in conferring the know-how required for more advanced jobs. With booming domestic demand for factory-made goods and extraordinarily low labor costs, India has the potential to become a viable manufacturing alternative to China in sectors ranging from apparel to auto parts.98

To maximize its growth, India must better utilize the enormous, young, and growing labor force that represents its most valuable economic asset, while also encouraging the development of larger, more productive enterprises with greater economies of scale. Doing so will necessitate the adoption of labor rules that protect workers, rather than jobs. Greater flexibility for employers could be combined with the introduction of an unemployment insurance system befitting a labor force that’s set to become the world’s largest within a decade.99

State-owned companies

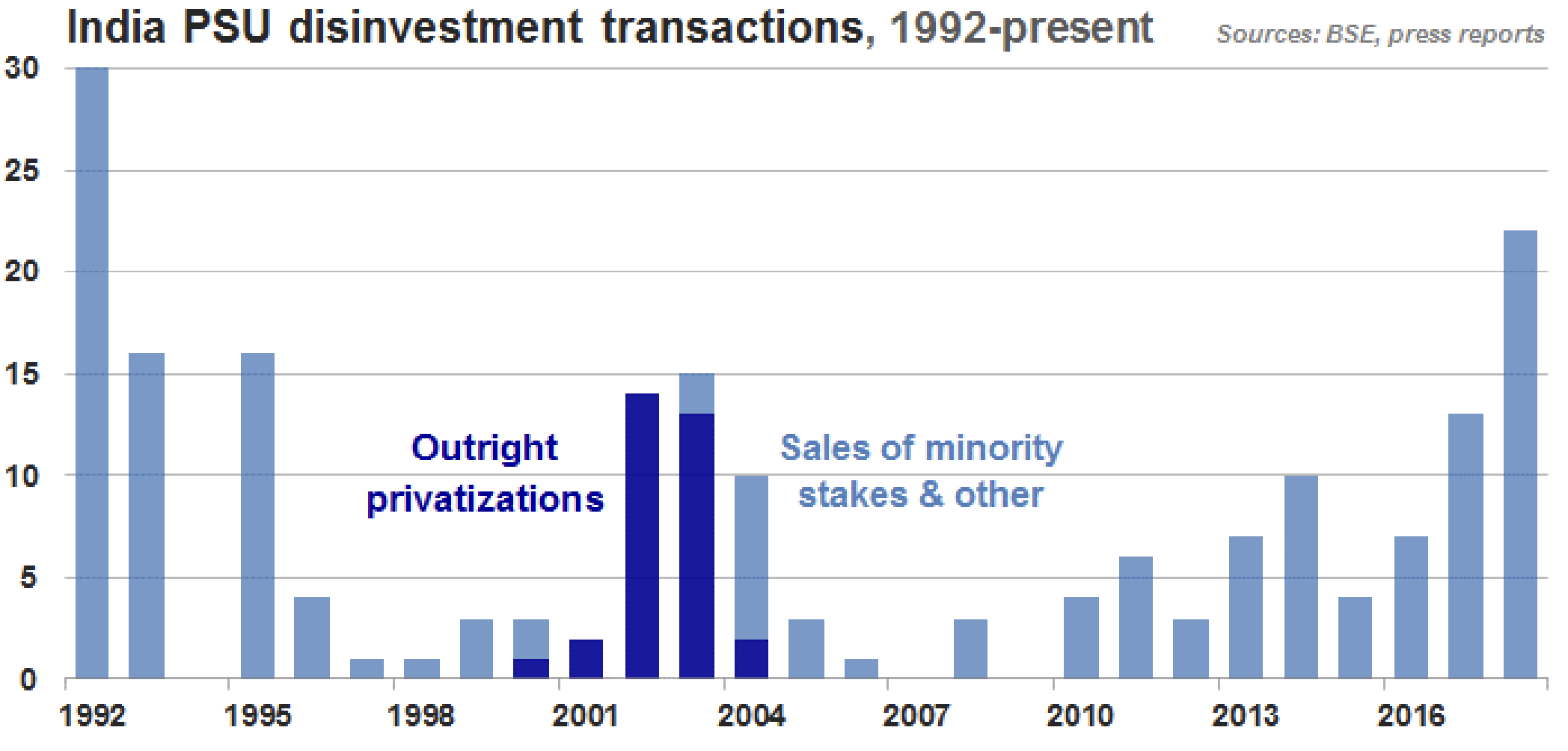

India’s central government is the majority shareholder of 257 operating companies, not counting public sector banks (covered in the following section), insurers, railroads, postal services, or state-level public enterprises.100 Vestiges of the country’s protracted love affair with central planning, these “public sector undertakings” (PSUs) include suppliers of artificial limbs, auto-rickshaws, coal, condoms, fighter jets, mutual funds, and tea.101 During the 1990s, successive governments’ PSU policies focused on “disinvestment”, i.e., the sale of non-controlling interests, primarily in under-performing firms. Until the turn of themillennium, stiff political opposition thwarted plans to sell minority stakes in all but the least commercially-viable PSUs.102

In the early 2000s, the government of Atal Bihari Vajpayee (prime minister 1998-2004) briefly overcame bureaucrats’ and labor unions’ resistance to “strategic sales”, i.e., outright privatizations, and to the loss of jobs and patronage these might entail. Under the oversight of a newly-created Department of Disinvestment, Vajpayee’s administration divested the Indian state’s controlling interests in over 30 largely-profitable PSUs, including bakery brand Modern Foods (sold to Hindustan Unilever), aluminum producer BALCO (sold to Sterlite Industries), telecom service provider VSNL (sold to Tata Group), and several hotels.103 In 2002, Japan’s Suzuki Motor Corporation was allowed to increase above 50% its stake in leading automotive manufacturer Maruti Udyog (until then a 50-50 joint venture between Suzuki and the Indian government); the government sold its remaining interest in the joint venture five years later.104

Following the end of the Vajpayee administration, India reverted to its earlier cautious, dithering approach to the PSUs. Via a smattering of additional minority stake sales, the number of publicly-listed non-bank PSUs rose to just over 40. Despite a moratorium on further outright divestments, however, the share of GDP attributable to central government-controlled companies continued to steadily decline (from 17% in the late 1980s to 9% today).105 Through a process dubbed “privatization by malign neglect”, the government retained control of PSUs – while allowing them to relentlessly cede market share to the nimbler, more efficient private competitors that emerged following India’s post-1991 liberalization.106 Key PSUs that the government remained unwilling to privatize, including once-prized franchises such as Air India and telecom giant BSNL, have since seen their value decimated, as they fell further and further behind dynamic private rivals.107

Though their contribution to India’s GDP has waned, PSUs continue to weigh on the broader economy’s productivity by trapping resources within inefficient, often unviable firms. In a country with a scarcity of both capital and skilled labor, PSUs sit on assets worth an estimated $500 billion, and provide guaranteed lifetime employment to over one million people.106 Based on an analysis of India’s 250 largest listed companies, the labor productivity of the country’s private-sector firms is roughly double that of its state-controlled enterprises.109 In aggregate, public-sector enterprises (including several lucrative monopolies) earn a nominal return on equity of barely 3% – a fraction of the 12% generated by a corporate India as a whole. In real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) terms, PSUs’ return on equity is negative.110

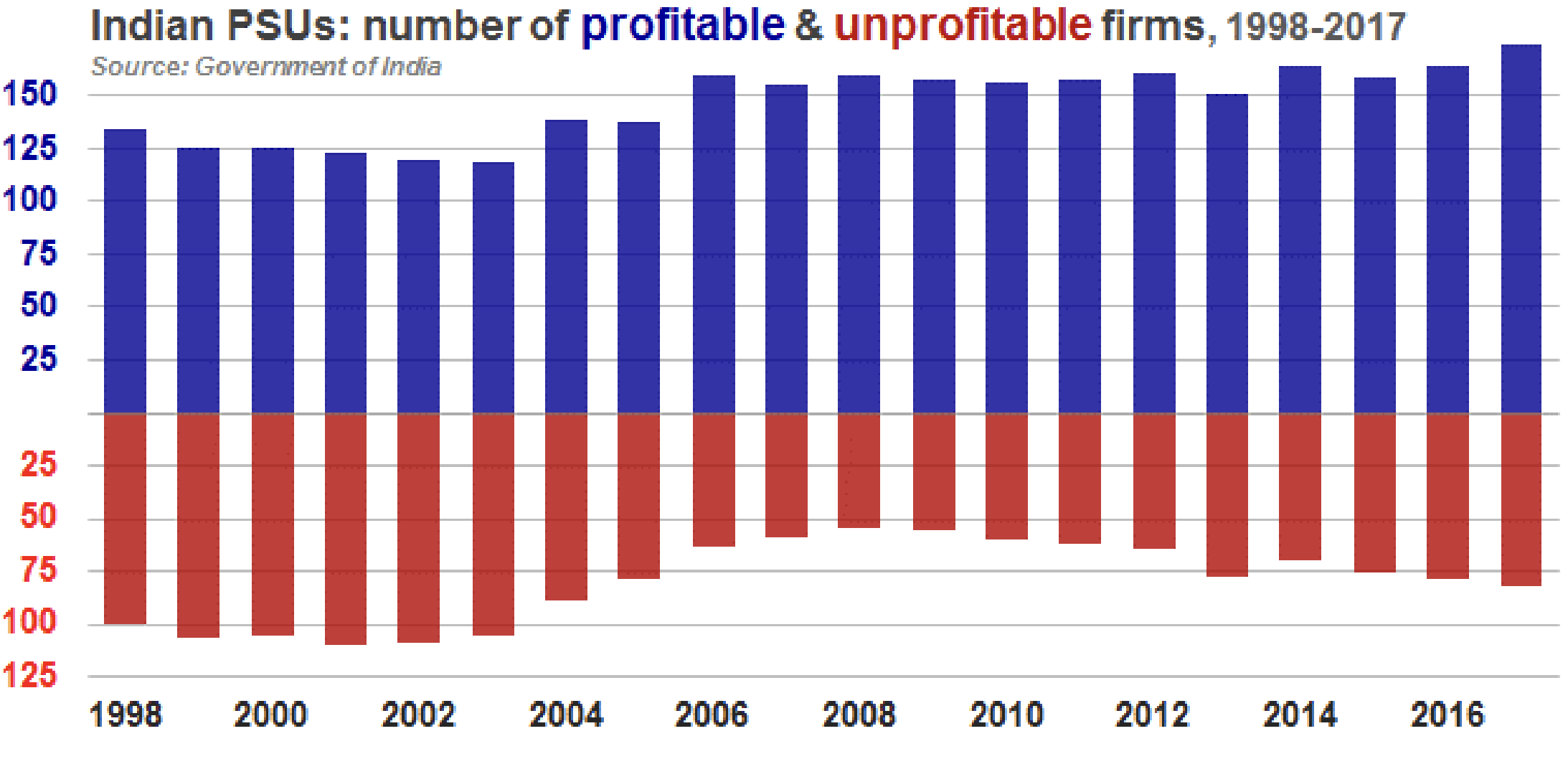

One-third of state-controlled firms are unprofitable.101 The most dysfunctional of these so-called “sick” PSUs include companies that, despite producing nothing for over a decade, still have thousands of workers clocking in to pick up their paychecks.111 Over the past decade, “sick” PSUs have racked up cumulative losses of ₹2.2 trillion ($33 billion) – enough to cover the government’s annual education budget nearly three times over.107 With muddled administrative structures that give neither PSU boards nor government ministries the autonomy to make key decisions, it’s unclear who, if anyone, is accountable for turning around underperforming public-sector firms.112 Instead of being overhauled or closed down, unprofitable enterprises have been kept afloat by ever-increasing public subsidies. In addition to exacerbating India’s misallocations of capital and labor, keeping insolvent PSUs on life support has deterred the entry and expansion of more-efficient private competitors – further undermining the dynamism of the wider economy.102

The problem with India’s PSUs is not their public ownership in and of itself; plenty of countries feature state-run success stories (e.g., Singapore and Germany).113 Rather, it has to do with the conflicting agendas of government officials (who tend to view PSUs as tools for promoting short-term political objectives) and the companies’ boards (which lack the autonomy to object to policies that undermine PSUs’ long-term viability). For example, political pressure to limit increases in user charges has prevented the revenues of India’s public-sector utilities, railways, and public transport authorities from keeping pace with their growing operational costs.114 Rationalizing PSUs’ costs is not an option, as bureaucrats and trade unions (abetted by India’s onerous labor laws) have obstructed not just efforts to shut down or privatize loss-making state enterprises, but even attempts to downsize PSUs’ obviously redundant workforces. For instance, state-owned Air India carries fewer passengers than private competitor SpiceJet, yet employs three times as many people.115 Despite owning lucrative landing and parking spots at international hubs including Heathrow and JFK, Air India has not generated a profit in over a decade.116

Similar faults are evident even in the case of the maharatnas (Sanskrit for “great gems”), a group of eight “crown jewel” PSUs. Although these flagship firms enjoy relatively strong market positions and the freedom to operate with a degree of financial autonomy, they feature the same deficiencies that bedevil their smaller peers, including unqualified, underpaid managers, pliant boards, and an inability to address glaring inefficiencies. The 83,000 employees of one maharatna, Steel Authority of India (SAIL), produce less steel than the 11,900 on the payroll of privately-owned JSW Steel.117 Any substantial profits generated by prominent PSUs are inevitably requisitioned to shore up the government’s finances or to foot the bill for unrelated, uneconomical projects. In 2016, the government ordered four of SAIL’s maharatna peers – Coal India, Gas Authority of India (GAIL), Indian Oil Corporation (IOCL), and National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC) – to fund the bailout of four shuttered urea plants formerly operated by Fertilizer Corporation of India, a “sick” PSU.118

Another maharatna, energy explorer Oil and Natural Gas Corp. (ONGC), was recently compelled to lever up its previously debt-free balance sheet in order to acquire (at a premium) the government’s controlling stake in oil refiner Hindustan Petroleum Corp. (HPCL). The Modi administration’s stated rationale for the transaction (achieving synergies via the formation of an integrated Indian oil giant) is contradicted by the government’s acknowledgement that the two companies will remain independently managed, and the fact that such a consolidation could in any case have been accomplished just as easily via a stock merger (rather than a cash acquisition).119 In reality, the ONGC-HPCL deal was simply the easiest way for the government to plug a shortfall in fiscal revenues following last year’s roll-out of a national value-added tax (GST, detailed in an upcoming dispatch).120

During his campaign for prime minister, Narendra Modi declared his belief that “government has no business to be in business”.106 His administration has gone further than its predecessors, including by at least floating the idea of divesting not only “sick” firms, but also relatively successful PSUs. Nevertheless, the government’s only high-profile privatization proposal to date addresses one of the worst-performing PSUs of all, half-dead Air India – and even that plan has encountered political and financial obstacles.121

A more politically-courageous overhaul of India’s PSUs would focus on benefiting the public, not on pampering the 0.01% of Indians lucky enough to have secured a cushy job with one of these uneconomic dinosaurs.122 Divesting just half of the government’s stakes in operating businesses would yield in the neighborhood of $250 billion – enough, in combination with the private capital that sum could draw in, to boost India’s investment in schools, roads, and other sorely-needed public infrastructure by 2.5% of GDP for the next decade.123

Banking system

The dominance of state enterprises remains most entrenched in India’s banking industry. Although the government has licensed new private-sector entrants since 1993, to this day 21 public-sector banks (PSBs) account for the vast majority of all lending in the country. Legacies of Indira Gandhi’s 1969 nationalization of financial firms, the PSBs have all become publicly-traded companies over the past quarter-century, starting with the 1993 IPO of the nation’s largest bank, State Bank of India.124 However, the Indian government remains the controlling shareholder in all 21 PSBs, and is barred by current law from reducing its stake below 51%.125

All Indian banks (whether state-owned or private) are subject to government mandates that crowd-out private-sector borrowing and steer capital toward relatively low-productivity uses – thereby dragging down the productivity and growth potential of the broader economy. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) enforces a complex array of lending directives that collectively regulate the allocation of over half of banks’ assets. For example, “priority sector lending” rules stipulate that 40% of credit extended by any bank must be to small-scale farmers, “micro” enterprises, persons indebted to informal moneylenders, and other designated categories of borrowers.126 Interest rate ceilings restrict banks’ ability to cover the high transactional costs associated with priority sector lending, which typically involves making small loans to large numbers of borrowers.127

Separately, all banks are compelled to invest 19.5% of their deposits in central- or state-government debt; at most PSBs, the share of deposits invested in government bonds is closer to 30%.128 The ability of PSBs to generate profits, or Banking system Dispatches from India India’s unfinished revolution at least minimize losses, is further undermined by populist giveaways – invariably timed to coincide with elections – such as periodic “waivers” of farmers’ loans, the lion’s share of which are with PSBs (see the agriculture section for more details).

India’s private banks are, at least, free to underwrite the rest of their loan books based on credit risk. At the PSBs, by contrast, lending is politically-driven even when not formally guided by government directives. For proof, look no further than the RBI’s public data – which reveal election-year spikes in lending to farmers, with the largest influxes of credit occurring in the most politically-competitive districts.129 The employees of PSBs are de facto civil servants, with their performance often judged primarily by their ability to grow the bank’s loan book, and their pay linked to government pay scales (the head of State Bank of India, for example, makes around $40,000 a year).130 Because their career advancement depends on playing it safe, PSB bankers lend disproportionately to large companies, agricultural interests, and other politically-favored constituencies, rather than to more dynamic medium-sized firms or – for fear of being accused by anti-corruption agencies of soliciting kickbacks – to new borrowers in general.131

Accounting for 70% of the Indian banking system’s overall lending but nearly 90% of its total bad debts, India’s PSBs are the center of a banking crisis that has been years in the making.132 After emerging unscathed from the global financial crisis, Indian banks embarked on a lending spree. Led by the PSBs, they funneled credit to infrastructure developers, mining companies, politically-connected conglomerates, and other firms cashing in on an investment boom that came to an abrupt end in 2012.133

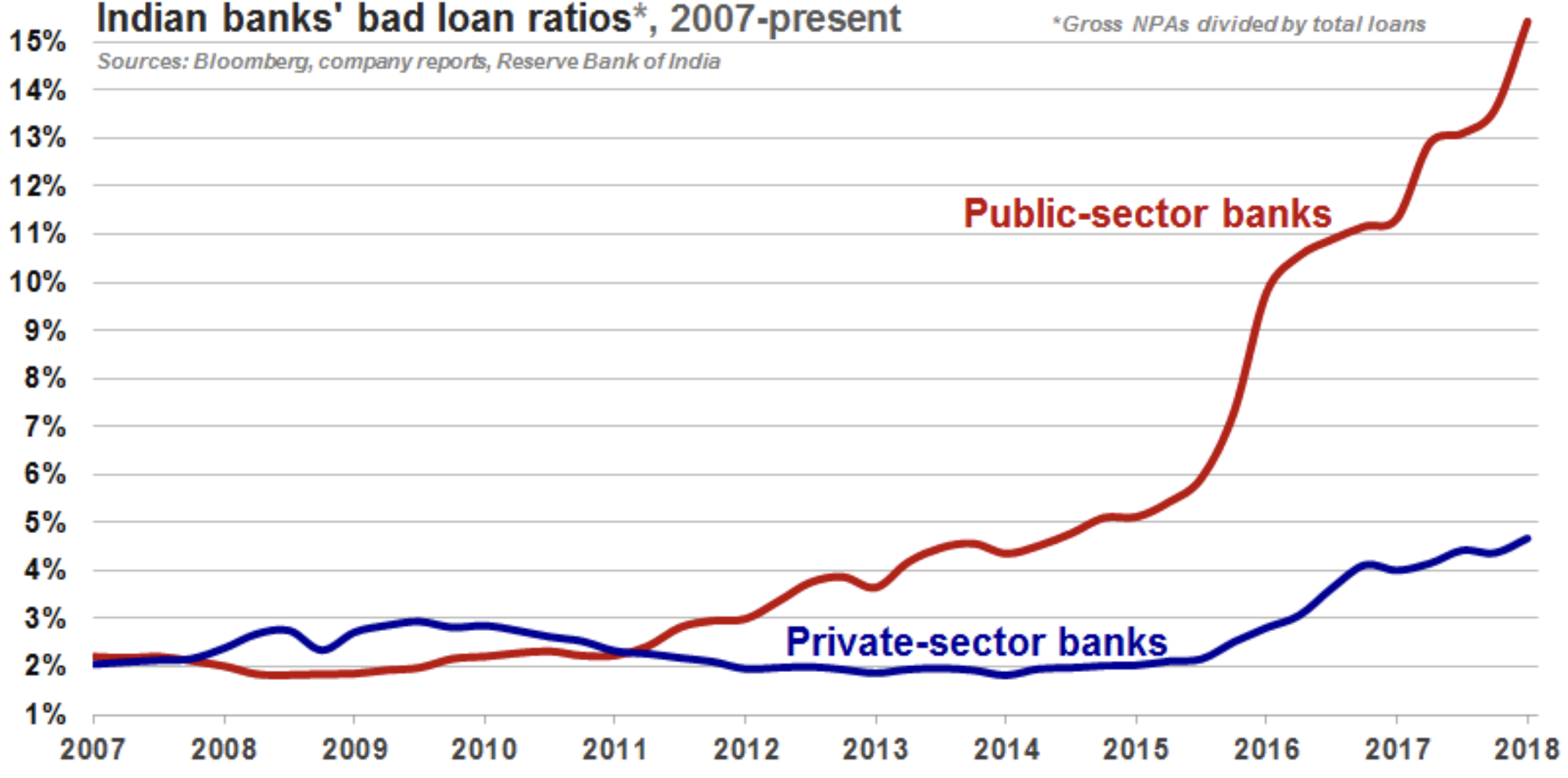

Indian banks’ bad loans began to escalate that year, as many borrowers found themselves unable to service their debts in the face of weakening demand, rising interest rates, and court decisions annulling ill-gotten mining and energy licenses. That uptick in delinquencies has since metastasized into a crisis largely as a result of a dysfunctional bankruptcy process that, prior to major recent reforms (detailed below), was highly susceptible to abuse by crony capitalists.134 Today, over 15% of PSBs’ loans are non-performing – more than triple the ratio of bad loans at the country’s private-sector banks.135 On average, investors value the PSBs at just one-half of their stated book value. The combined market capitalization of all 21 PSBs substantially trails that of a single private competitor, HDFC Bank, founded in 1994.136

Under the old system, it took over four years to foreclose on a delinquent loan in India, with an average recovery rate of 26 cents on the dollar (compared to one year to recover 82 cents on the dollar in the United States).137 Taking advantage of PSBs’ slow-moving bureaucracies and India’s hodgepodge of overlapping, open-ended legal procedures, crooked industrialists were known to drain their companies of cash (e.g., by awarding overpriced contracts to family members) while engaging in drawn-out negotiations with the various bank syndicates attempting to collect their overdue money.138 If they happened to run into an insufficiently docile PSB loan officer, tycoons could count on their friends in the finance ministry to set the banker straight. Today, one-quarter of the banking system’s ₹9.6 trillion ($140 billion) in non-performing loans is attributable to just 12 once-favored industrial firms, dubbed the “Dirty Dozen” by Indian newspapers.139

Until recently, India’s PSBs were doing their best to muddle through this mess. In order to avoid recognizing losses (and the risk of depleting their equity levels below regulatory minimums), the banks simply rolled over or “restructured” (i.e., eased payment terms on) overdue loans. Along with this “extend and pretend” strategy, PSB officials remained unwilling to auction off non-performing assets to distressed-debt investors, for fear of being accused of selling them too cheaply should the new holders manage to recover the borrowed money in full.131

Among the tycoons who had long taken advantage of India’s pliable public-sector lenders, the most notorious is Vijay Mallya, a flamboyant liquor heir. Shortly after hosting a multi-day 60th birthday party headlined by Enrique Iglesias, Mr. Mallya – self-proclaimed “king of good times” –fled to London, leaving his mostly state-owned lenders on the hook for $1.4 billion.140 More recently, high-end jeweler Nirav Modi (no relation to India’s current prime minister) absconded to Hong Kong following accusations that he fraudulently obtained $2 billion worth of loans from government-controlled Punjab National Bank.141

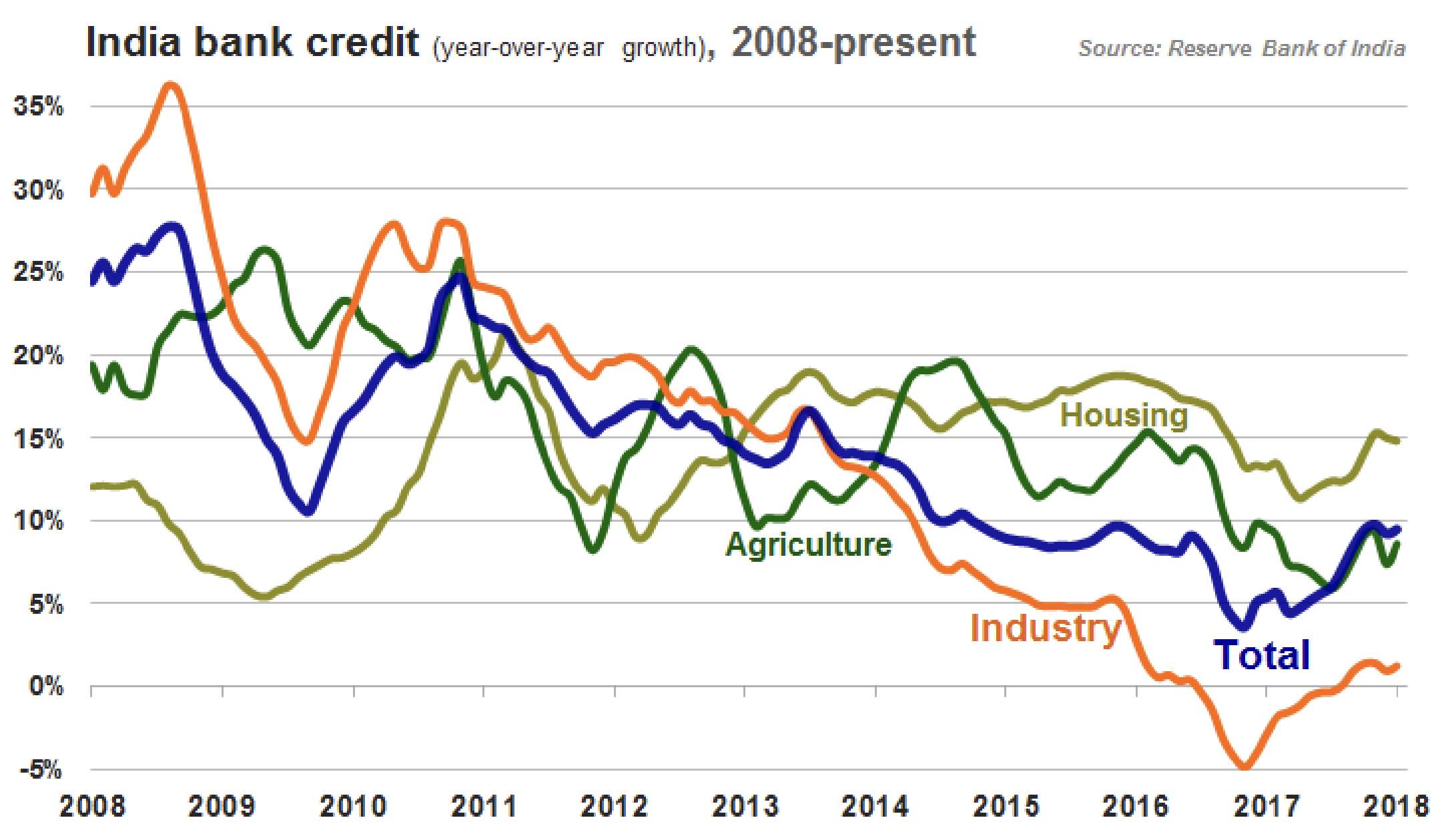

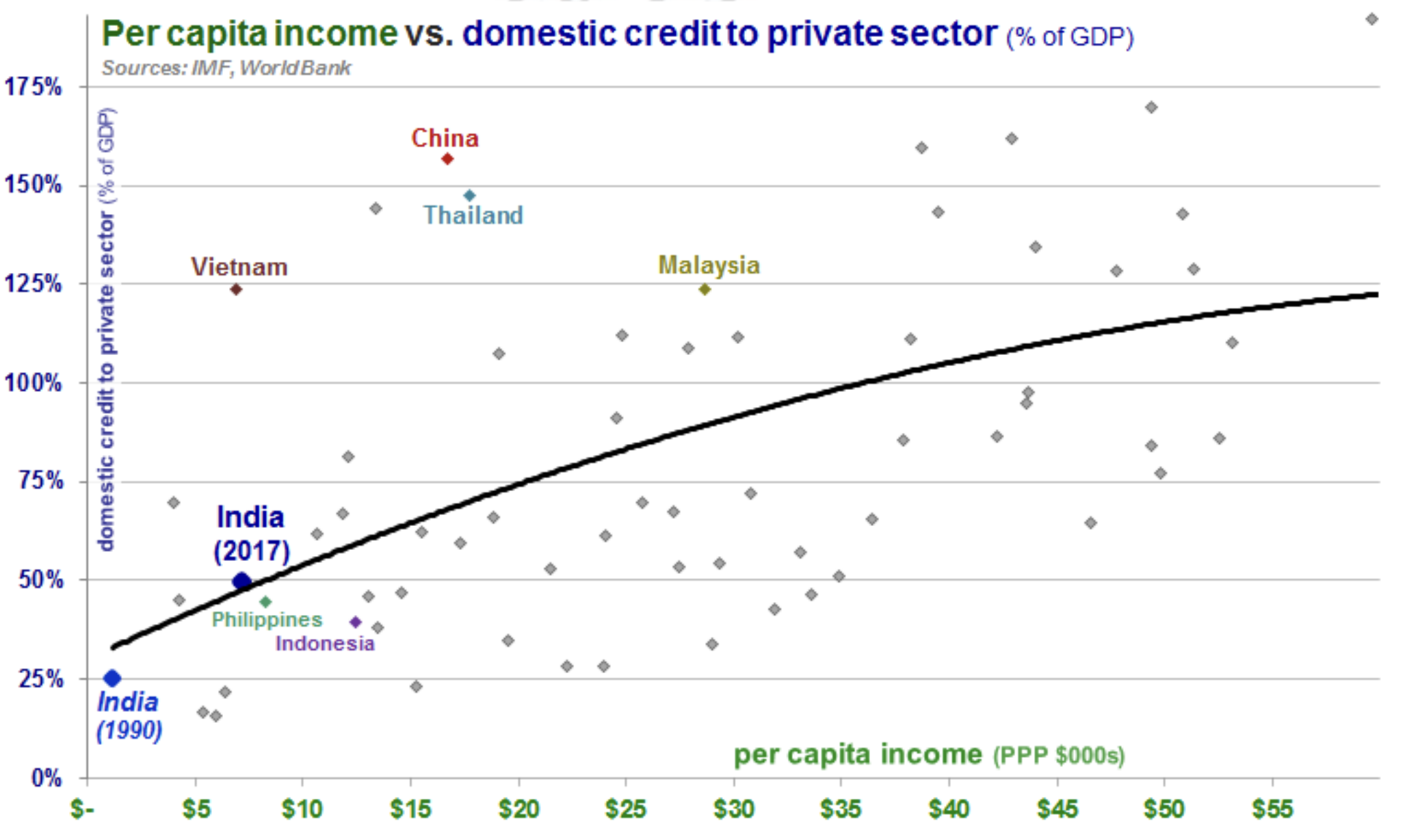

Meanwhile, the mounting strains on Indian banks’ balance sheets began to curtail their capacity to make new loans – and, by extension, the country’s ability to fund new investment. Despite India’s buoyant GDP growth, its banks’ overall loan books are currently growing more slowly than at the peak of the global financial crisis; lending to industrial firms is shrinking in real (inflation-adjusted) terms.142 The amount of credit provided to India’s private sector recently dipped to just 50% of GDP – half the average among Asia’s other major developing economies.143

Since Modi’s 2014 election victory, the government has responded to the PSBs’ increasingly egregious state by cracking down on both the mismanaged banks and their most notorious borrowers. In early 2016, the RBI forced banks to make provisions for “restructured” loans, and to begin including those accounts in their reported non-performing assets.144 Later that year, India implemented its first national bankruptcy law, the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC). Replacing an antiquated system of competing proceedings, the IBC consolidates cases pertaining to insolvent companies into a single forum.138

The IBC is transforming how India treats bankrupt firms. The law gives specialized tribunals the power to fire the board of an insolvent company and run it on behalf of its lenders, who must then reach a deal within a strict nine-month timeline before the business is automatically sold for scrap – drastically speeding up liquidation proceedings that once dragged on for a decade or longer.145 Controlling shareholders who drive businesses into default are now explicitly barred from retaining ownership. Already, investors ranging from Canadian pension manager to global private equity firms have set up specialized funds dedicated to acquiring distressed Indian assets, starting with the 1,500 companies that have already been declared insolvent under the new system.146

The largest of the “Dirty Dozen” corporate loan default cases, Bhushan Steel, was also the first to be resolved under the IBC. In May 2018, the company’s lenders sold its operations to Tata Steel for ₹352 billion ($5 billion) – representing a 37% haircut to Bhushan’s over ₹560 billion ($8 billion) in outstanding dues.147 The bankrupt steelmaker’s former controlling shareholder, Neeraj Singal, is awaiting trial on allegations that he bribed the chairman of Syndicate Bank, a PSB that subsequently granted loan extensions to Bhushan.148

The combination of the IBC and crony capitalists’ dwindling influence in Delhi promises to alleviate a key constraint on the expansion of entrepreneurial, innovative enterprises (and, by extension, on the productivity growth of the wider economy). By making it easier for businesses to fail, India’s new bankruptcy code and its crackdown on delinquent industrialists should help free up resources that had been trapped within unviable firms. However, the reforms achieved to date have failed to address the roots of the current banking crisis – the dysfunctional PSBs.

In October 2017, the government announced a ₹2.1 trillion ($32 billion) strategy to plug the capital shortfall resulting from the mark-down of the PSBs’ soured loans.149 The plan, part of which involves using money borrowed from the PSBs to buy the PSBs’ shares, resembles the one used to shore up the PSBs in the 1990s, following an earlier round of ill-advised lending.150 That bailout, along with various other bank rescues carried out over the past three decades, cumulatively cost Indian taxpayers nearly ₹1.5 trillion ($22 billion).151 Initially, the government declared that the newest recapitalization effort would be different, with banks’ eligibility for funds linked to the scope of their reform initiatives. When the first tranche of the bailout was disbursed in January 2018, however, all but one of India’s 21 PSBs received fresh capital, with a disproportionate share allocated to the banks with the highest levels of non-performing loans.152

Even this latest, colossal bailout may not be sufficient to clean up the PSBs’ balance sheets. The new capital, combined with the public banks’ existing ₹3.3 trillion in loan-loss reserves, should cover roughly 60% of their non-performing assets, assuming the latter do not escalate even further.135 The obvious way to plug any additional capital shortfall would be to turn to private investors – yet PSBs will be unable to sell shares at decent valuations unless they can assure stockholders that they will be allowed to lend on the basis of credit risk, rather than political diktats. Convincing investors would almost certainly require allowing them to inject enough capital to dilute the government’s stake in the PSBs below 50%. That, in turn, would necessitate new legislation – improbable, at least until after next year’s federal election.153

Similar to the unviable businesses that politically-connected cronies had long propped up with endless rounds of PSB loans, the PSBs themselves will likely remain money pits unless they resolve the structural factors behind their chronic need for bailouts. Political pressure leads PSBs to over-allocate credit to some categories of borrowers, while deterring them from lending to more eligible firms. The presumption that PSBs cannot fail erodes their underwriting discipline.154 By regularly recapitalizing poor performers, India’s government not only reinforces PSBs’ deficiencies, but also prevents more efficient banks from expanding market share – thereby undermining the financial sector’s capacity to finance investment in the real economy.83

The current bad loan crisis presents India with an opportunity to make bankers and investors, rather than politicians and taxpayers, responsible for the consequences of reckless lending. Ideas floating around Delhi include merging the weaker PSBs into their healthier peers, rolling the government’s bank shareholdings into an arms-length sovereign wealth fund, and committing to full-scale privatization at the higher market valuations that the PSBs would presumably achieve after being sufficiently recapitalized and reformed.153 The most common criticism of proposals to privatize the PSBs relates to their role in financing infrastructure, rural development, and other high priority areas that fail to attract adequate private capital. Rather than continuing to fill that gap with public money, however, India would be better off simply addressing the issues that have historically deterred private banks from underwriting investment in these sectors.

Realizing the half-fulfilled promise of 1991

Even if India were to keep policy on autopilot, its economy would likely still “chug along quite happily, growing faster than most other countries.” Buoyed by the nation’s highly favorable demographics, as well as the ongoing benefits of its initial round of post-1991 reforms, India’s scrappy entrepreneurs would continue overcoming red tape, and hundreds of millions of people would witness improvements in their standards of living.4

However, the opportunity cost of spurning a second phase of comprehensive economic liberalization would be enormous. Under our reform scenario, India’s average income would overtake China’s and Malaysia’s current per capita GDP by the mid-2030s – a decade earlier than if growth were to remain capped at the “business as usual” rate.

Over the 1992-2017 period, India’s GDP grew at a compound annual rate of 6.9%.156 The reforms discussed above would boost India’s GDP growth rate by an estimated 3 percentage points, relative to this “business as usual” scenario.

For a detailed discussion of the methodology used to calculate the contribution from each category of reforms to faster economic growth, please refer to Appendix B.

Because India’s agricultural sector, land market, labor laws, and state-owned companies form a Gordian knot of interconnected dysfunction, solving any of these areas’ problems requires reforming all the others, as well. India’s overstaffed agricultural workforce strains to eke out a living from fragmented, inefficient farms, yet onerous land restrictions and decrepit records stand in the way of the obvious remedy: encouraging the irrigation and mechanization of a smaller number of larger plots, while shifting more farmers into higher-productivity jobs in the industrial or services sectors.

“India grows at night while the government sleeps [...]

should India not grow during the day as well?”157

Gurcharan Das, “India Grows At Night”

At the same time, cumbersome land and labor rules stifle Indian firms’ ability to generate enough jobs to gainfully employ the millions already being added to the country’s non-agricultural workforce. The resources available to fund the expansion of growing firms are further constrained by the lending directives and loan waivers authorities use to prop up struggling farmers, by the PSBs’ politically-riven credit allocation, and by the capital trapped within zombie PSUs.

The tentative steps being floated by India’s current government, from recommendations for agricultural market reform to plans for resuming state-owned company privatizations, are encouraging – but not enough. If Indians’ enthusiasm for free-market policies is to be sustained, they will need to see proof that reforms benefit everyone, not just businessmen and politicians. As was the case in 1991, the impediment to broad-based job growth and improvement in living standards is not an excess of liberalizing reform, but an inadequacy. While India’s economy has already achieved extraordinary growth, its performance should be measured against a higher benchmark – the one set by Manmohan Singh in his July 1991 speech to Parliament, in which he declared the government’s role to be “empowering [India’s] people to realize their full potential.”158

* * *

Andrei Stetsenko

June 13, 2018

Appendix A: productivity

Differences in productivity explain much of the disparity in living standards across countries, and even modest changes in an economy’s long-term compound rate of productivity growth can drive enormous variation in its GDP per capita.159

Because statistics on employment and output are readily available and comparable (particularly relative to data on physical capital, technology, education, and other inputs), labor productivity (i.e., the economic output per hour worked) – calculated by dividing total output by total labor inputs (i.e., the number of hours worked) – is the most common metric for measuring productivity over time and/or between countries. Growth in labor inputs is dependent not only on demographic variables (e.g., increases in population and/or rates of labor market participation), but also on the availability of enough jobs to absorb new entrants to the workforce. Meanwhile, growth in labor productivity is linked to improvements in physical capital (e.g., infrastructure and machinery), human capital (i.e., education), technology, managerial techniques, the legal and institutional environment, and other factors that enable workers to generate more output per hour of labor.

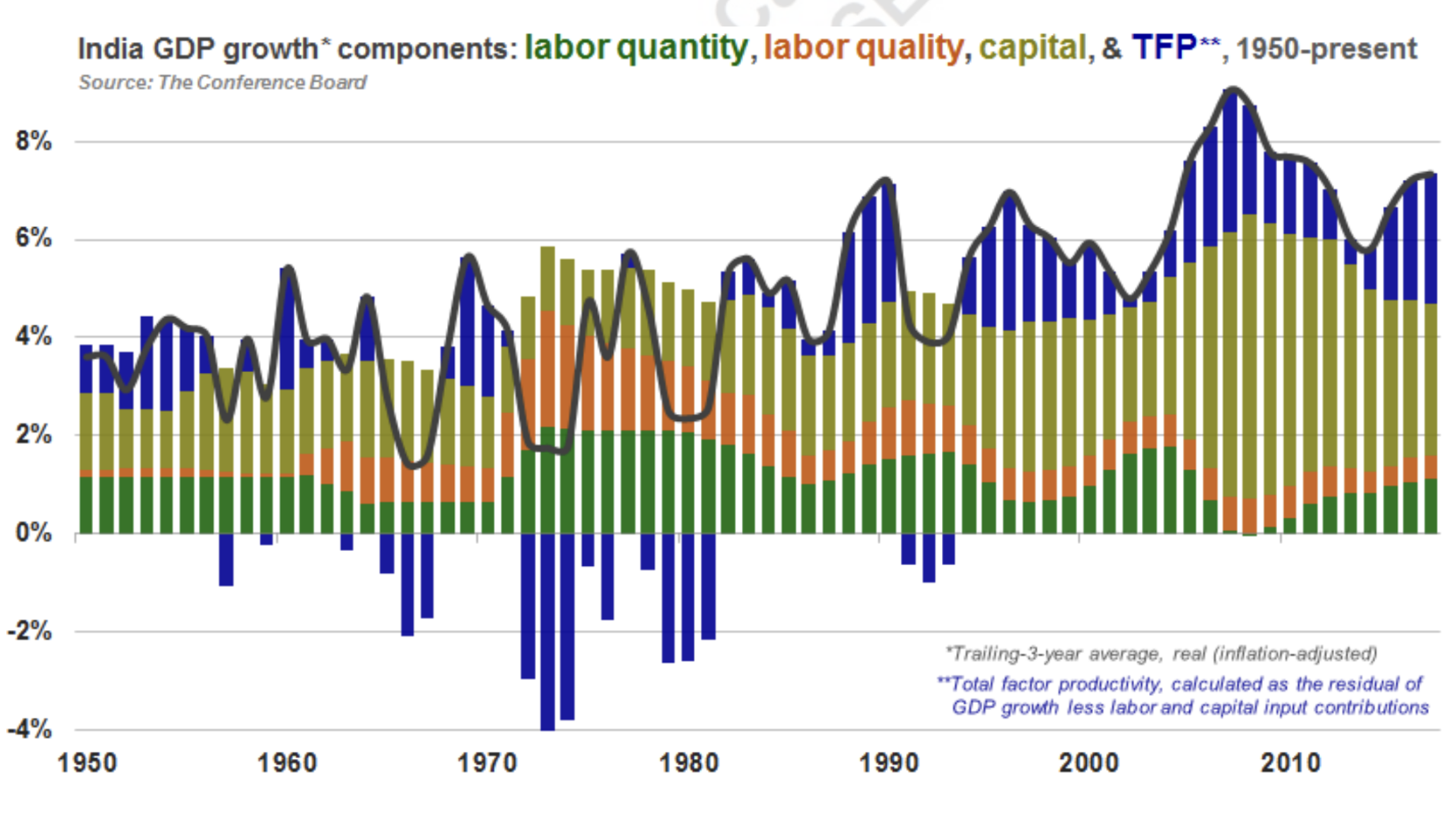

To estimate the contribution of multiple inputs to economic development, economists utilize a more complex metric known as total factor productivity (TFP), sometimes called multi-factor productivity (MFP). Calculated as the residual portion of growth in output (i.e., GDP) not explained by growth in either labor inputs (i.e., the number, hours, and education/skills of people working) or capital inputs (i.e., the stock of physical plant and equipment), TFP is used to measure the allocative efficiency of those inputs. With the contribution to GDP growth of growth in labor inputs (ΔL) and growth in capital inputs (ΔK) weighted based on labor compensation’s share of GDP (β), this can be formulated using the following equation:

% ΔGDP = % ΔTFP + (% ΔL*(β)) + (% ΔK*(1-β))

Over the past quarter-century, TFP has been the second-biggest contributor to India’s overall GDP growth, after growth in capital inputs.160

Appendix B: growth projection methodology

The notion that reducing distortion in factor markets spurs faster economic growth is supported by decades of undisputed, cross-country data. There are different ways of quantifying the benefits of improved resource allocation, however, and ours is admittedly simplistic.

To estimate the growth boosts from major labor, land, agriculture, and public-sector company reforms, we calculated the increase in economic output, relative to India’s actual 2017 GDP, driven by plugging in each of the assumptions outlined below (in isolation, to avoid double-counting). We then calculated the ten-year compound annual growth rate required to achieve each increase.

(A) Labor reforms (1.3 percentage points)

(i) Continued shift of workers out of agriculture and into higher-productivity sectors: we assume a decline over the coming decade in the agricultural share of employment from 44% to 35%.

- That 9 percentage point reduction is equivalent to the actual decline in the agricultural share of India’s employment over the preceding decade.

(ii) Increased labor participation rate: we assume an increase in the employed proportion of the working-age (15-64) population from 58.1% to 59.0%.

(iii) Narrowed dispersion in productivity between large industrial firms and their smaller counterparts (discussed on page 21): we assume a 25% reduction in the difference between U.S. and Indian industrial productivity dispersion, implying a 10% boost to overall industrial sector productivity.

(B) Land reforms (0.7 percentage points)

(i) Improved allocation of land (discussed on page 17): we assume a 20% increase in output per worker; we assume this boost applies to the industrial sector only.

- Note: Research published by McKinsey & Co. calculates a substantially higher potential benefit from such reforms, estimating that land market distortions reduce India’s GDP growth by 1.3 percentage points annually.161

(C) Agriculture reforms (0.6 percentage points)

(i) Narrowed gap in productivity between agriculture and the rest of India’s economy: we assume that agricultural sector productivity, expressed as a percentage of the overall Indian economy’s labor productivity, rises from 39% to 44%.

- The latter figure matches this metric’s actual 1998 level, as well as the median ratio of agricultural to overall labor productivity among the world’s 50 largest economies.20

- Note: A simple way of approximating this metric is by dividing the agricultural share of GDP by the agricultural share of employment.

(D) PSU/PSB reforms (0.4 percentage points)

(i) Narrowed gap in productivity between public- and private-sector companies we assume that the productivity of state-owned companies (including public-sector banks), expressed as a percentage of the overall labor productivity of the industrial and service sectors, rises from 50% to 84%.

- This calculation is informed by an analysis we conducted of India’s 250 largest listed companies (referenced on page 25), which estimated that the per-employee output of private-sector firms is roughly double that of state-owned enterprises. We assume this gap closes for two-thirds of public-sector companies, but not for the one-third of state-controlled firms that are currently economically unviable.

- Note: McKinsey calculates a higher potential benefit from such reforms, estimating that government ownership of businesses (including banks) reduces India’s GDP growth by 0.7 percentage points annually.162

Legal Information and Disclosures

The views expressed are the views of the author as of the date indicated on each posting; such views are subject to change without notice. Farley Capital L.P. (Farley Capital) has no duty or obligation to update the information contained herein. Further, Farley Capital makes no representation, and it should not be assumed, that past investment performance is an indication of future results. Any discussion regarding investment returns or financial projections are provided as illustrative examples only and no inference shall be made therefrom regarding the potential for returns on any investment discussed. Moreover, you should be aware that all types of investments involve a significant degree of risk, and wherever there is potential for profit, there is also the possibility of loss.

This content is being made available for informational and educational purposes only and should not be used for any other purpose. The information contained herein does not constitute and should not be construed as financial, legal, or tax advice, or as an offering of advisory services. The information contained herein shall not constitute an offer to sell, or a solicitation to subscribe for, interests in any investment vehicle managed by Farley Capital, which offer or solicitation will only be made to qualified investors and accompanied by a private placement memorandum, subscription agreement, and other related offering documents. Certain information contained herein concerning economic trends and performance is based on or derived from information provided by independent third-party sources. Farley Capital believes that the sources from which such information has been obtained are reliable; however, it cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of such information and has not independently verified the accuracy or completeness of such information or the assumptions on which such information is based.

This content, including the information contained herein, may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted in whole or in part, in any form without the prior written consent of Farley Capital.

References and Notes

1 The Economist (February 2015). Cover page. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/printedition/covers/2015-02-19/ap-la-na

2 Palit, Amitendu. “Economic Reforms in India: Perpetuating Policy Paralysis” (March 2012). Institute for South Asian Studies, ISAS Working Paper No. 148. Retrieved from https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/143840/ISAS_Working_Paper_148_-Economic_Reforms_in_India_30032012163947.pdf

3 The Economist. “India’s economy: One more push” (July 2011). Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/node/18988536

4 The Economist. “India’s economy: The half-finished revolution” (July 2011). Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/node/18986387

5 Dhume, Sadanand. “RIP, Indian National Congress” (October 2014). The National Interest. Retrieved from http://www.aei.org/publication/rip-indian-national-congress

6 Taseer, Aatish. “Narendra Modi and India’s Dashed Economic Hopes” (May 2016). The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/28/opinion/narendra-modi-and-indias dashed-economic-hopes.html

7 Roberts, Adam. “The Modi era begins” (May 2014). The Economist. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/blogs/banyan/2014/05/indias-next-prime-minister-0

8 Choudhury, Chandrahas. “20 Years Later, India's Transformation Is Incomplete: World View” (July 2011). Bloomberg News. Retrieved from Bloomberg terminal, NSN LP2GHN6K50XS [GO] 9 Bharatiya Janata Party, Facebook page. “Good days are coming…” (April 2014). Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/BJP4India/photos/pb.121439954563203.-2207520000.1409498973./754393537934505

10 World Bank. International Comparison program database (2017), GDP per capita based on purchasing power parity. Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD 11 As defined by the Indian government’s Rangarajan committee, which in 2014 set the poverty line at ₹47/day in cities, or ₹32/day in rural areas. Government of India, Planning Commission. Report of the Expert Group to Review the Methodology for Measurement of Poverty (2014). Retrieved from http://planningcommission.nic.in/reports/genrep/pov_rep0707.pdf; Bloomberg L.P. India Real GDP (Annual YoY %). Retrieved from Bloomberg terminal, EHGDINY Index

12 United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects (2015), File POP/15-1: Annual total population (both sexes combined) by five year age group, major area, region and country, 1950-2100, Medium fertility variant. Retrieved from https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp; Choudhary, Vidhi. “The children of liberalization” (July 2016). Livemint. Retrieved from http://www.livemint.com/Politics/8bylBNRIdFm92fkeybqeZP/The-children of-liberalization.html

13 Bowring, Philip. “A Bumpy Road to Economic Liberalization in India” (September 1995). The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1995/09/05/news/05iht-edbow.t.html 14 Padmanabhan, Anil. “We should have done what we have in half the time: Montek Singh Ahluwalia” (February 2016). Livemint. Retrieved from http://www.livemint.com/Politics/ ID0wWgOVEPIiFwms2yJvuM/We-should-have-done-what-we-have-in-half-the-time.html 15 World Bank. World Development Report 2013: Jobs (October 2012), Chapter 3: Jobs and productivity. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/11843 16 The Conference Board, Total Economy Database. Output, Labor, and Labor Productivity, 1950- 2018 (March 2018), TCB Adjusted data. Retrieved from https://www.conferenceboard.org/data/economydatabase/index.cfm?id=27762

17 Keim, Geoffrey and Wilson, Beth. “India’s Future: It’s About Jobs” (November 2007). Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, International Finance Discussion Paper 913. Retrieved from https://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/ifdp/2007/913/ifdp913.pdf

18 Ravindran, Shruti. “Indian land bill: ‘We’re losing not just land, but a whole generation of farmers’” (May 2015). The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/global-development professionals-network/2015/may/12/agriculture-in-india collapse-farmer-debt-land-acquisition-bill 19 Tangtipongkul, Kaewkwan. “Rates of Return to Schooling in Thailand” (August 2015). Asian Development Bank, Asian Development Review, 32:2, pages 38-64. Retrieved from https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/ 10.1162/ADEV_a_00051; World Bank. World Development Indicators (March 2017), International Labour Organization, Employment in agriculture (% of total employment, modeled ILO estimate). Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.AGR.EMPL.ZS

20 International Labour Organization. ILO database of labour statistics, Employment by sector – ILO modelled estimates (November 2017). Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/ilostat; World Bank. World Development Indicators (March 2018), Agriculture, value added (% of GDP). Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NV.AGR.TOTL.ZS

21 Government of India, Ministry of Agriculture, Department of Agriculture & Co-operation, Agriculture Census Division. “Agriculture Census 2010-11” (February 2014). Retrieved from http://agcensus.nic.in/agcen201011.html; United Nations, Food and Agriculture Organization. Land Use – Agricultural Area (2015). Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/RL

22 Parija, Pratik and Pradhan, Bibhudatta. “A Good Monsoon Is Little Comfort for Despairing Indian Farmers” (June 2017). Bloomberg News. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/ 2017-06-14/a-good-monsoon-is-little-comfort-for despairing-indian-farmers

23 World Bank. World Development Indicators (May 2018), UN FAO, Agricultural irrigated land (% of total agricultural land). Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.LND.IRIG.AG.ZS; Fensom, Anthony. “This Debt Debacle is Damaging India’s Economy” (June 2017). The National Interest. Retrieved from http://nationalinterest.org/feature/farm-waivers-are-damaging-indias economy-21230

24 Kapur, Rahul et al. “Transforming Agriculture Through Mechanisation” (December 2015). Grant Thornton; Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry. Retrieved from http://www.grantthornton.in/insights/articles/transforming-agriculture through-mechanisation 25 United States Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service. World Agricultural Production (April 2018). Retrieved from https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/circulars/production.pdf 26 The Economist. “Farming in India: In a time warp” (June 2015). Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/news/asia/21656241-india-reforming-other-bits-its-economy-not farming-time-warp

27 Chatterjee, Shoumitro and Kapur, Devesh. “Understanding Price Variation in Agricultural Commodities in India: MSP, Government Procurement, and Agriculture Markets” (July 2016). National Council of Applied Economic Research. Retrieved from http://www.ncaer.org/events/ipf 2016/IPF-2016-Paper-Chatterjee-Kapur.pdf