Click here to access this dispatch as a formatted PDF.

Part one of this series (“India before 1991: tiger caged”) examined the highly statist economic strategy implemented by Nehru, India’s first prime minister. Envisioned as a means of protecting the country from neo-colonial exploitation by industrialists and foreigners, Nehru’s policies had the effect of limiting the opportunities available to India’s poor while sheltering a handful of crony capitalists from both domestic and foreign competition. Indira Gandhi’s decision to double down on those policies in the 1960s and 70s further stifled competition, deterred entrepreneurship, and incentivized corruption, while deepening India’s isolation from the global economy.

The relatively minor changes Indira and Rajiv Gandhi managed to implement during the 1980s, such as loosening controls on capacity expansion and cutting taxes, are best described as “pro-business” rather than “pro-market”. They helped improve the profitability of incumbent industrial producers and commercial establishments, but failed to dismantle barriers to competition and trade – postponing the kind of transformational liberalization that would benefit all Indians,3 and making the economy increasingly dependent on unsustainable fiscal deficits underwritten by costly foreign financing.

By the end of the 1980s, India was lurching toward the edge of a financial precipice.4 At the same time, the nation’s politics began to descend into escalating turmoil, and the window of opportunity that Rajiv Gandhi had been granted to liberalize policy seemed “unlikely to be repeated.” Nevertheless, the conclusion of The Economist’s May 1991 “tiger caged” report – which predicted that “[t]he tiger will not be freed for some yet” – was about to proven dramatically wrong.5

With Rajiv Gandhi bogged down in scandals and confidence in the economy badly damaged, the Congress party performed poorly in the 1989 election. Mr. Gandhi’s former finance and defense minister, V. P. Singh, managed to piece together a weak coalition government (led by his short-lived Janata Dal party) “that was united only in its opposition to [Congress]”.6

In the summer of 1990, V. P. Singh traveled to Kuala Lumpur for an international summit and was stunned by the rapid progress Malaysia had made since his previous visit to that country just five years earlier.7 He asked his top advisor – the Oxford-educated economist Montek Ahluwalia – to examine what India needed to do in order to replicate the robust growth rates in Southeast Asia and China. The resulting internal study, which would later form the blueprint for India’s post-1991 reforms, provided the most detailed and comprehensive outline to date of the policy changes India needed to undertake.8 In July 1990, this report – dubbed the “M document” – was leaked to the press, sparking huge controversy.9

Even as V. P. Singh attempted to manage the political fallout from the “M document”, the August 1990 Iraqi invasion of Kuwait suddenly exacerbated India’s already worrisome trade and financial imbalances.10 Conflict in the Gulf caused the price of crude oil and petroleum products – which accounted for over a quarter of India’s import bill11 – to double,12 and contributed to economic slowdowns in both the United States and the Soviet Union – the first- and second-largest destinations for Indian exports, respectively.13

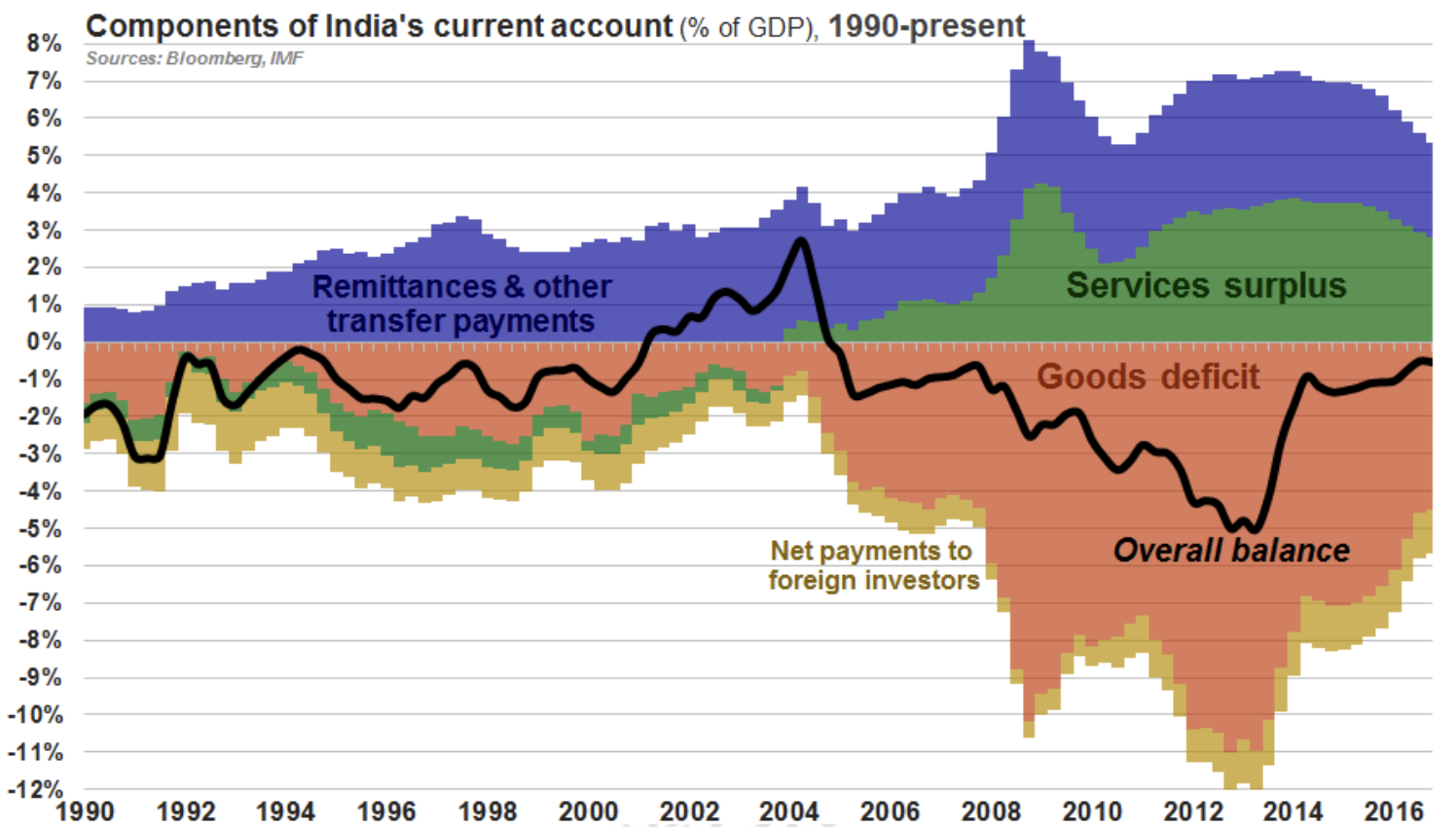

In what remains the largest air evacuation in history (and a source of great national pride), the Indian government airlifted home over 170,000 Indian citizens who had been working in Kuwait at the time of the invasion.14 However, the combination of the subsequent sharp decline in remittances from overseas Indians, costlier oil, and a slump in exports was disastrous for India’s current account.15 Between the first six months of 1990 and the second half of the year, the nation’s current account deficit jumped from $2 billion to over $5 billion.16

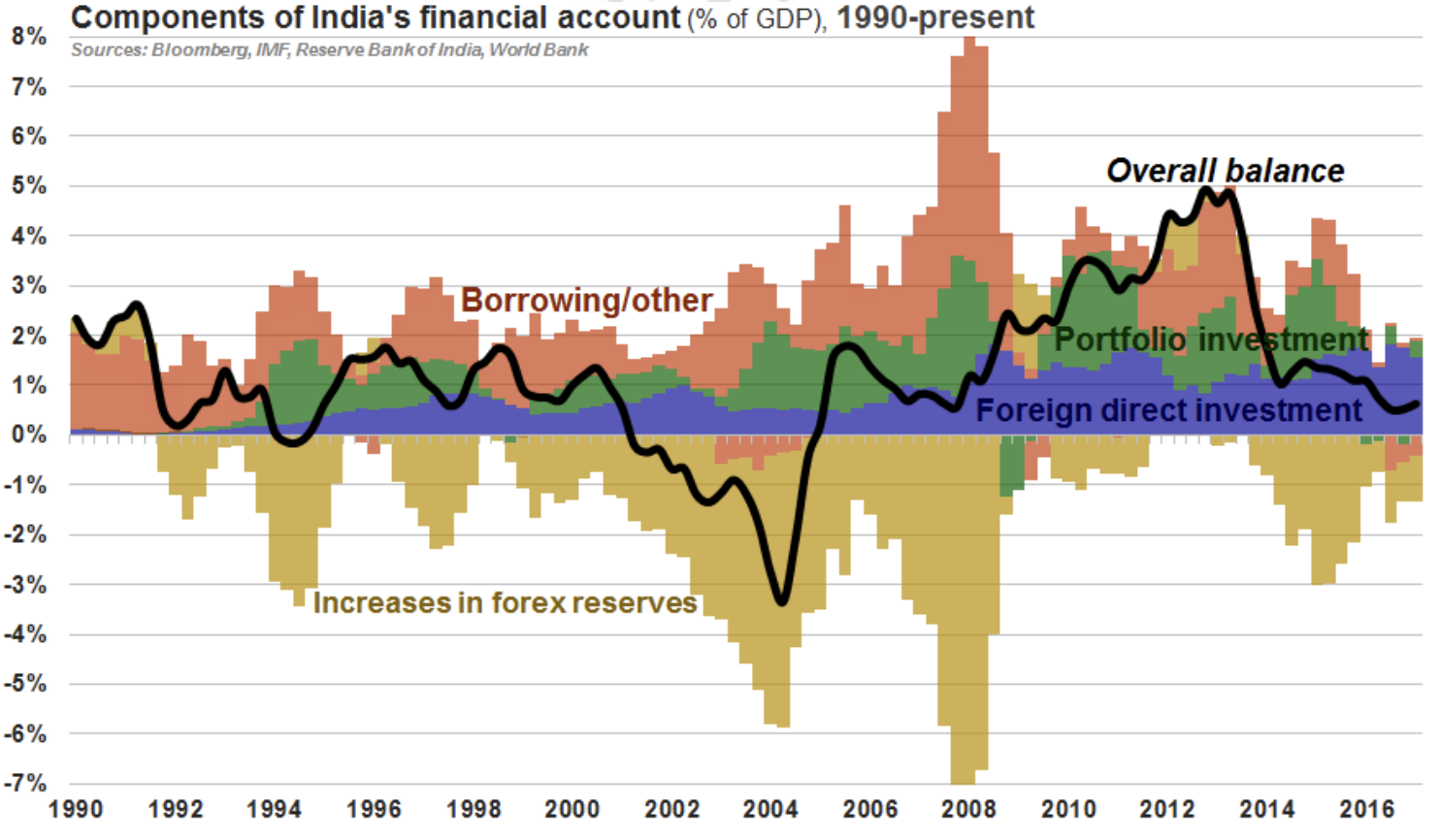

A current account deficit is principally a trade deficit, which implies a net flow of capital out of a country. A financial account surplus is the capital that must flow into a country to offset that trade deficit. For a detailed primer on balance of payments terminology, please refer to the appendix of part one of this series (“India before 1991: tiger caged”).

Within weeks of the invasion of Kuwait, V. P. Singh authorized his officials to reach out to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – making his the first Indian administration in a decade to request a loan from the Fund. Despite India’s increasingly precarious financial position, V. P. Singh knew that borrowing from the IMF remained politically contentious. As soon as it became public knowledge that a government was applying for assistance, its leaders “would be attacked in parliament and in the press for subjugating the country’s interests to foreign domination.” To reduce his political vulnerability, V.P Singh limited his request to $1.8 billion – equivalent to one-quarter of India’s IMF quota, the maximum it could draw without promising specific policy reforms18 – even as it became increasingly obvious that more would be needed to bridge the nation’s financing gap.

The government tried to buy itself more time with various traditional crisis-fighting measures, including a tightening of import licensing and surcharges on bank finance for imports.19 However, a series of sectarian disputes brought down V. P. Singh’s administration in November 1990, when a breakaway faction of his party defected before a no-confidence vote. That splinter group installed its leader, Chandra Shekhar, as prime minister – though its survival was entirely dependent on the backing of the Rajiv Gandhi-led Congress party.20 Immediately after Shekhar took office, his new government sent two top officials to Washington “on a secret mission” to seek a larger funding package from the IMF, and began preparing an emergency budget proposal.21

In January 1991, the start of the Gulf War destabilized Shekhar’s already-weak administration. As U.S.-led coalition forces began a massive aerial bombing campaign in Iraq, his government struggled to preserve a neutral stance amid heated domestic opposition to the refueling of U.S. warplanes at Mumbai’s international airport.22 The public outcry forced Shekhar to delay the presentation of his emergency budget to parliament – “effectively [putting] discussions with the IMF on hold.”23 In March 1991, right as the plan was finally on track to be submitted to parliament, the Congress party pulled its support for the government24 – toppling Shekhar’s nascent administration (a “four-month comic interlude”) and triggering yet another election.25

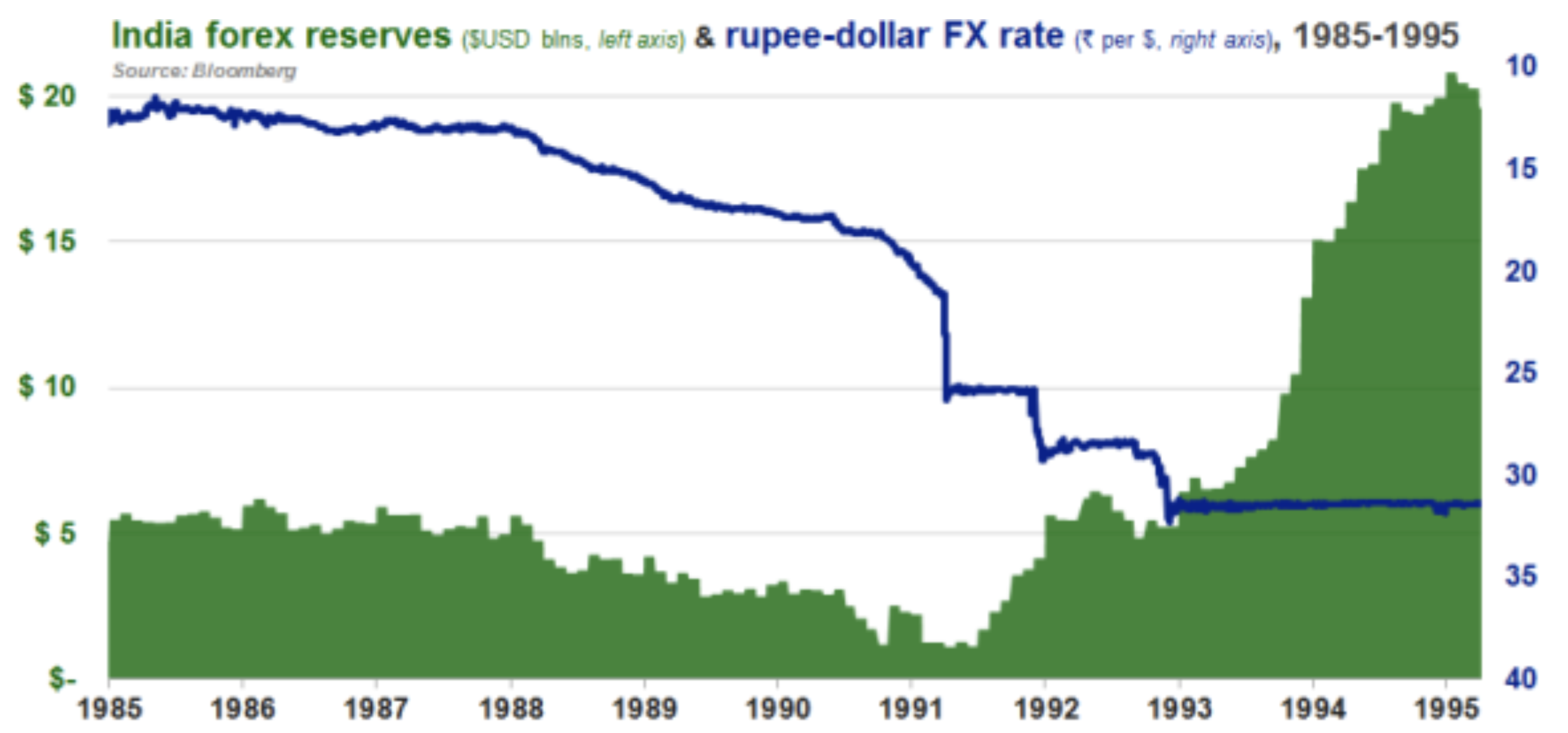

Increasingly wary foreign lenders saw India’s trade and financial imbalances deteriorating, its borrowers (including the government) facing rating downgrades, and its politics in disarray. As the country’s political turmoil deepened, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) alerted the Ministry of Finance that Indian banks were losing their ability to access dollar funding from global lenders.10 The RBI expended its foreign currency reserves in an attempt to defend the value of the rupee (which was pegged to a basket of the dollar, yen, pound sterling, and deutsche mark).26

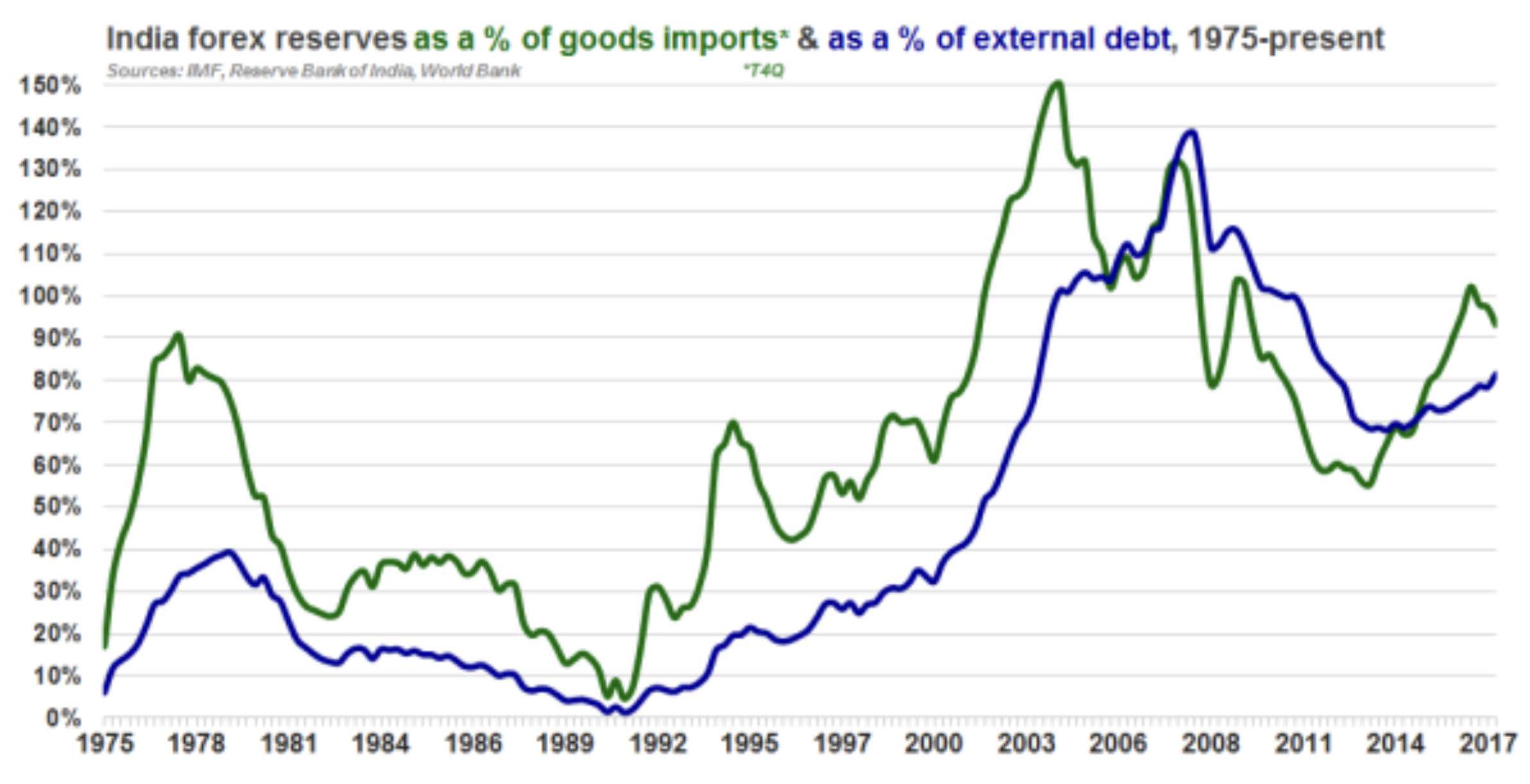

By the time the Shekhar government fell, those reserves had dwindled to $2.2 billion – barely enough to cover a month’s worth of imports.27 Locked out of commercial funding and with no prospect of support from the teetering Soviet Union, India was on the brink of default – kept afloat only by a limited credit line from the IMF. It was increasingly clear that the nation was not going to get further aid without significant conditions attached.

The first thing Indians noticed about the official election manifesto released by the Congress party on April 16, 1991 was that it contained no mention of the word “socialism”. Deviating from Congress’s decades-old economic dogma, the platform promised to deepen the economic liberalization that the party’s leader, Rajiv Gandhi, had partially implemented during the previous decade.

Opposition politicians accused Congress of “trying to take the country to the pre 1947 mentality”. Critics heaped scorn on Mr. Gandhi for being “in a hurry […] to reverse his grandfather’s [Jawaharlal Nehru’s] belief in self-reliance”, declaring that he had “outdone the former British Prime Minister, Mrs. Margaret Thatcher […] in his bid at economic liberalisation”.28 Barely a month later, on May 21, 1991 – one day after the first round of India’s staggered, multi-phase election – Rajiv Gandhi was assassinated.

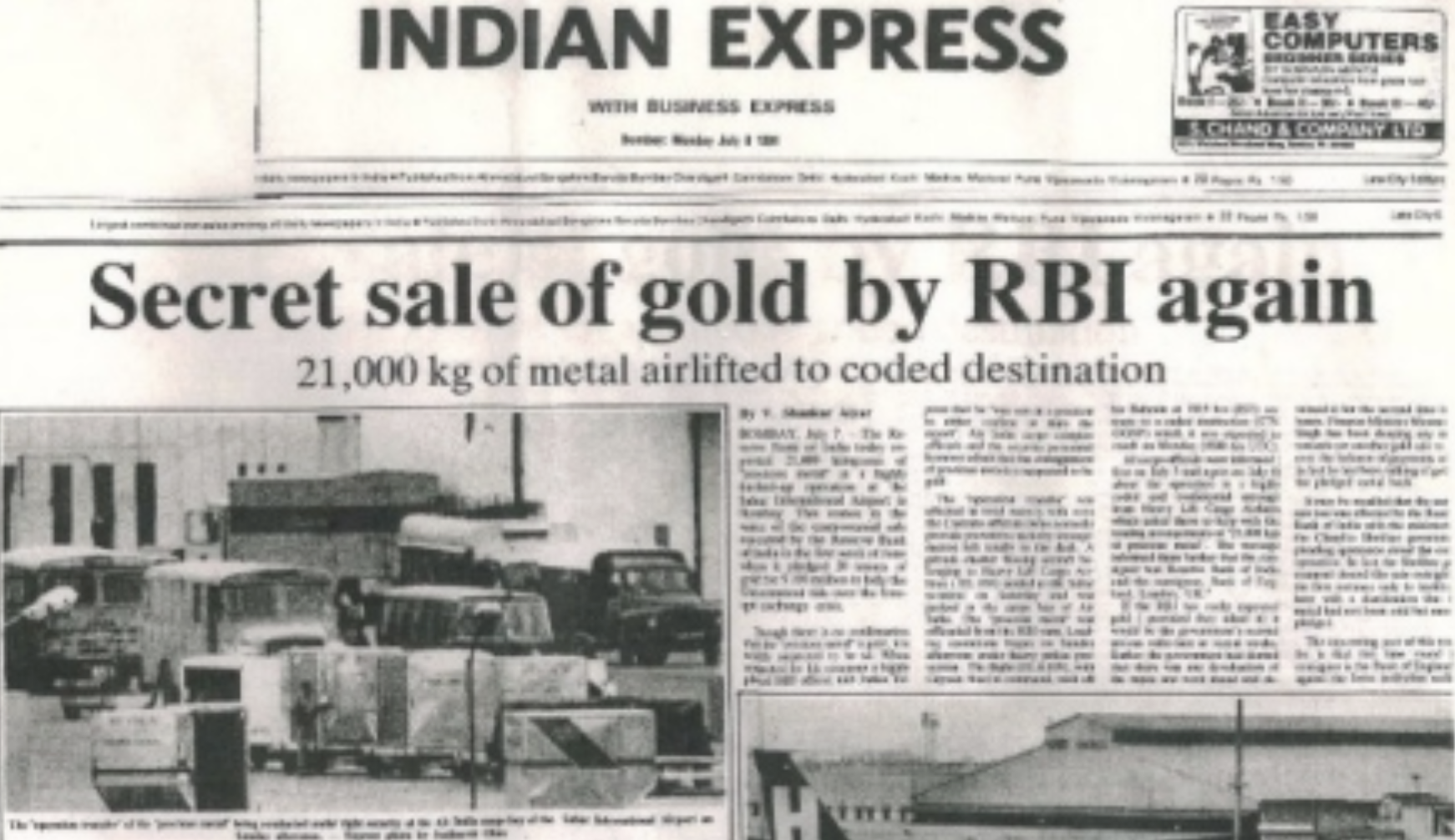

As confidence crumbled, authorities postponed the election and resorted to a desperate stopgap measure, raising $234 million from the Union Bank of Switzerland (UBS) by sending 20 tons of gold on a Swissair flight to Zurich.29 For a nation with a deep-rooted reverence for gold as a traditional symbol of prosperity,30 this humiliating news – much more so than S&P’s subsequent downgrade of India’s sovereign credit rating to junk31 – “finally drove home the point that something drastic had to be done to save the Indian economy,”32 which “was so wrecked that India was pawning its family jewelry.”33

Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination in the middle of India’s 1991 election suddenly left Congress without a leader. After Sonia Gandhi, Rajiv’s Italian-born widow, declined to take the reins, the party was forced to turn to P. V. Narasimha Rao (prime minister 1991-96). A fixture of national politics for decades, the 70-year-old Rao had held ministerial positions in the administrations of both Indira and Rajiv Gandhi.

Sporting a plain dhoti (a traditional men’s garment worn wrapped around the waist) and “the pout of an ageing uncle”,35 Rao had a “highly underwhelming appearance” and the “charisma of a dead fish”.36 With a secretive, taciturn personality that contrasted sharply with the charm and exuberance of his young predecessor,37 Rao was widely seen as a frail, indecisive, and unambitious “fuddy-duddy”.38

When polling resumed in mid-June, sympathy for the Gandhis ensured that Congress won the largest number of seats in parliament – though not an absolute majority.39 Chosen “because he was seventy, quiet, dull, and […] threatened no one”, the party’s newly-installed leader, Narasimha Rao, proceeded to form a coalition government that nobody expected would last for very long.40 Luckily for India, Rao’s underwhelming exterior concealed a shrewd, ideologically flexible pragmatist who was about to defy all expectations.

Late on June 20, 1991 – the eve of his swearing-in as India’s tenth prime minister – Rao was briefed on India’s balance of payments crisis, the previous government’s secret discussions with the IMF, the pressure to devalue the rupee, and the mortgaging of the central bank’s gold bullion. “I didn’t know it was this bad…” was his reaction42 upon being informed that the RBI’s reserves had been depleted to just $1.1 billion – enough to cover only two weeks’ worth of imports.27 A protectionist “who confessed that he did not understand economics”, Rao became an economic liberalizer that evening.43

A novelist and technology enthusiast who wrote fiction in multiple languages and taught himself computer code, Rao cut his teeth as a wartime propagandist during India’s 1962 conflict with China.41 While serving as foreign minister in the 1980s, he observed how Deng Xiaoping – whom he would later call his “philosophical mentor”36 – was able to portray a wholesale reorientation of China’s economy as a mere extension of Mao’s vision.44

By the time Rao reached India’s highest political office, he had learned how to harness a fast-moving narrative, sideline his adversaries, and push through unpopular policies – skills that were about to prove extraordinarily useful as he steered the world’s largest democracy out of a desperate crisis and into a new economic era.45

Over the following 33 days, India overhauled its entire industrial, trade, and fiscal policy, kick-starting a transformation that would irreversibly alter the very nature of the country’s economy.46 On June 21, Rao made the first of several pivotal decisions – appointing as his finance minister Dr. Manmohan Singh, an economist and former governor of the RBI who happened to be familiar with the managing director of the IMF.47 Decades earlier, while studying at Cambridge and Oxford, Singh had written about the flaws of India’s import substitution policies.48 Now, he and the rest of Rao’s cabinet would be given free rein to implement tough reforms to the controls that had for so long stifled India’s development.49

To avoid the perception that his government was acting under foreign pressure, Rao instructed his officials “to do whatever had to be done immediately” and preemptively, rather than wait for the IMF to lay out conditions. On the evening of June 21, the prime minister told his chief of staff “not to wait for formal orders and instead, [to] start working closely” with the newly-installed Singh.50

In the decade leading up to 1991, much of India’s political class continued to view economic liberalization – in particular, the softening of import controls – as the cause of India’s problems, and saw re-regulation as the cure for the country’s current account deficit.52 Few recognized or acknowledged that the combination of protectionism and the License Raj had created a vicious circle of misguided policy – with scarcity triggering calls for more controls, which further inhibited production, resulting in even more scarcity, corruption, and hostility to the prospect of liberalizing reform.

Throughout the 1980s, however, a small but vocal faction within India’s economic establishment had endorsed and outlined most of the liberalizing policies that would later come to comprise the post-1991 reforms. As a result, pro-liberalization technocrats “were already in place with papers and draft policy documents” when circumstances presented them with a historic opportunity to push through momentous changes.53 Singh was one of several of these economic dissidents – many of them educated at or employed by U.S. universities and institutions such as MIT and the World Bank – whom Rao was able to draft into key roles overseeing and implementing the reforms.54

On June 22, Rao used his first nationally-televised address to notify Indians that his government intended to do more than simply resolve the immediate crisis. In contrast to his predecessors – who had responded to India’s balance of payment crises of 1966 and 1981 with tentative, half-hearted tweaks to its statist economic system – Rao began to exploit India’s brief dependence on the IMF “to direct policy attention towards the competitiveness of the Indian economy.”8 Declaring that “there [were] no soft options left,” Rao announced that his administration was committed to “removing the cobwebs” obstructing India’s path towards industrialization and international competiveness.24 On July 9, he stated in another speech that the “bulk of government regulations and controls on our economic activity have outlived their utility.”55

Without losing any time, Rao’s officials began proactively implementing the reforms they anticipated would be demanded by the IMF, starting with a long overdue exchange rate adjustment. In the first four days of July 1991, Singh devalued the rupee by 25% against the U.S. dollar.56 Midway through the process, Rao reportedly lost his nerve and attempted to halt the devaluation. By the time he contacted his cabinet, however, the deed was done, and Singh had already announced it to the public. It was too late to turn back.57

“When 1991 happened, suddenly it felt like somebody opened the jail door, came in, and removed all the shackles, and said, ‘You’re free. You can go.’”58

Suresh Krishna, industrialist

“We do not have time to postpone adjustment and stabilisation. We must act fast and act boldly […] I do not minimise the difficulties that lie ahead on the long and arduous journey on which we have embarked. But as Victor Hugo once said, ‘no power on earth can stop an idea whose time has come.’ I suggest that the emergence of India as a major economic power in the world happens to be one such idea. Let the whole world hear it loud and clear. India is now wide awake.”4

Manmohan Singh’s speech to Parliament on July 24, 1991

The whirlwind of reforms that followed came to be known as the New Economic Policy (NEP).59 At noon on July 24, 1991, the government announced plans to dismantle the License Raj, open most sectors to private-sector competition, and scrap the MRTP Act (the 1969 law that had prevented business expansion).60

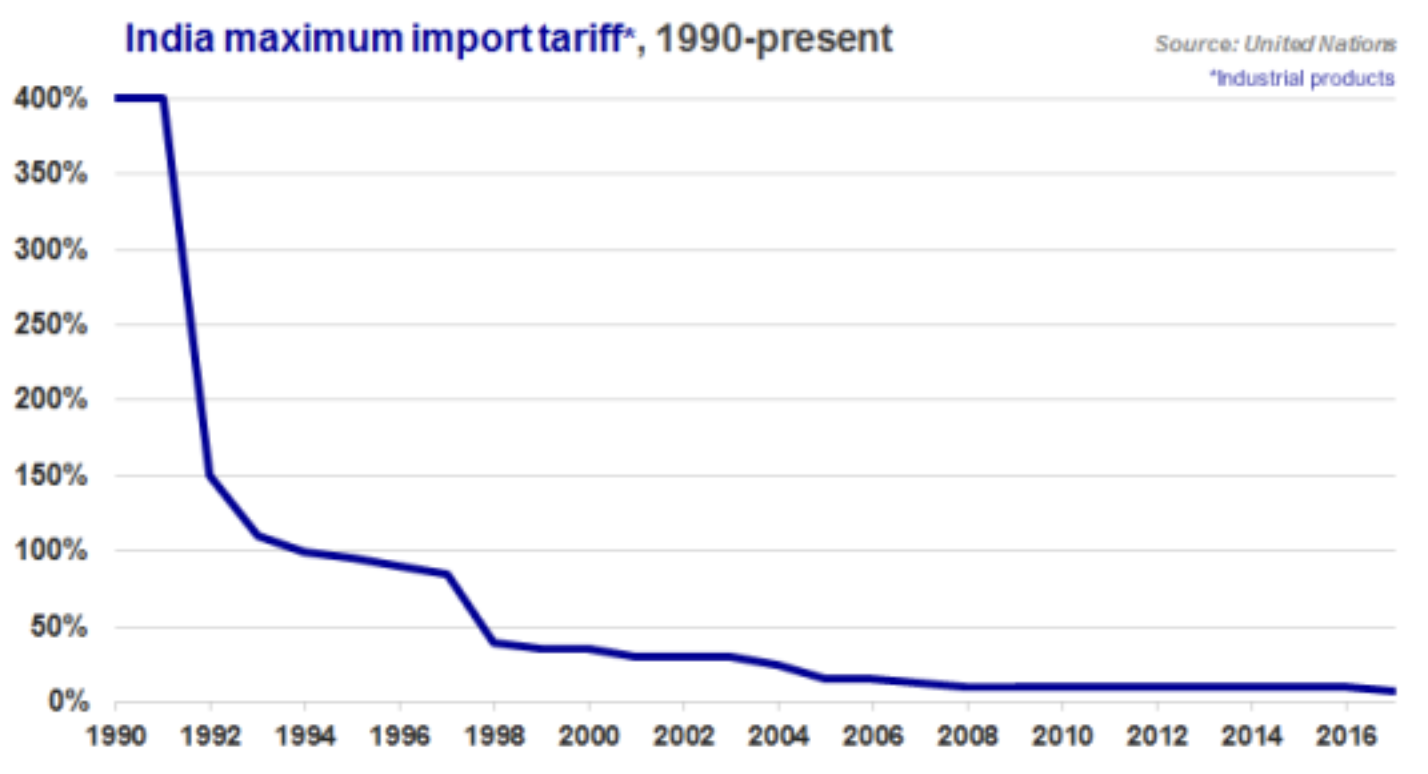

Four hours later, Manmohan Singh presented to India’s Parliament a budget that eliminated most price controls, did away with quantitative restrictions on production and imports, slashed import duties, liberalized interest rates, initiated a “disinvestment” policy for partially privatizing state-owned companies, instituted an automatic approval process for foreign ownership of up to 51% of direct investments in most industries (replacing the 40% ceiling that had been imposed back in 1973), and handed responsibility for capital markets regulation to a new, independent agency. Declaring that “[t]he room for maneuver, to live on borrowed money or time, does not exist anymore”, Singh added that this would all be achieved concurrently with a significant reduction in the government’s fiscal deficit.4

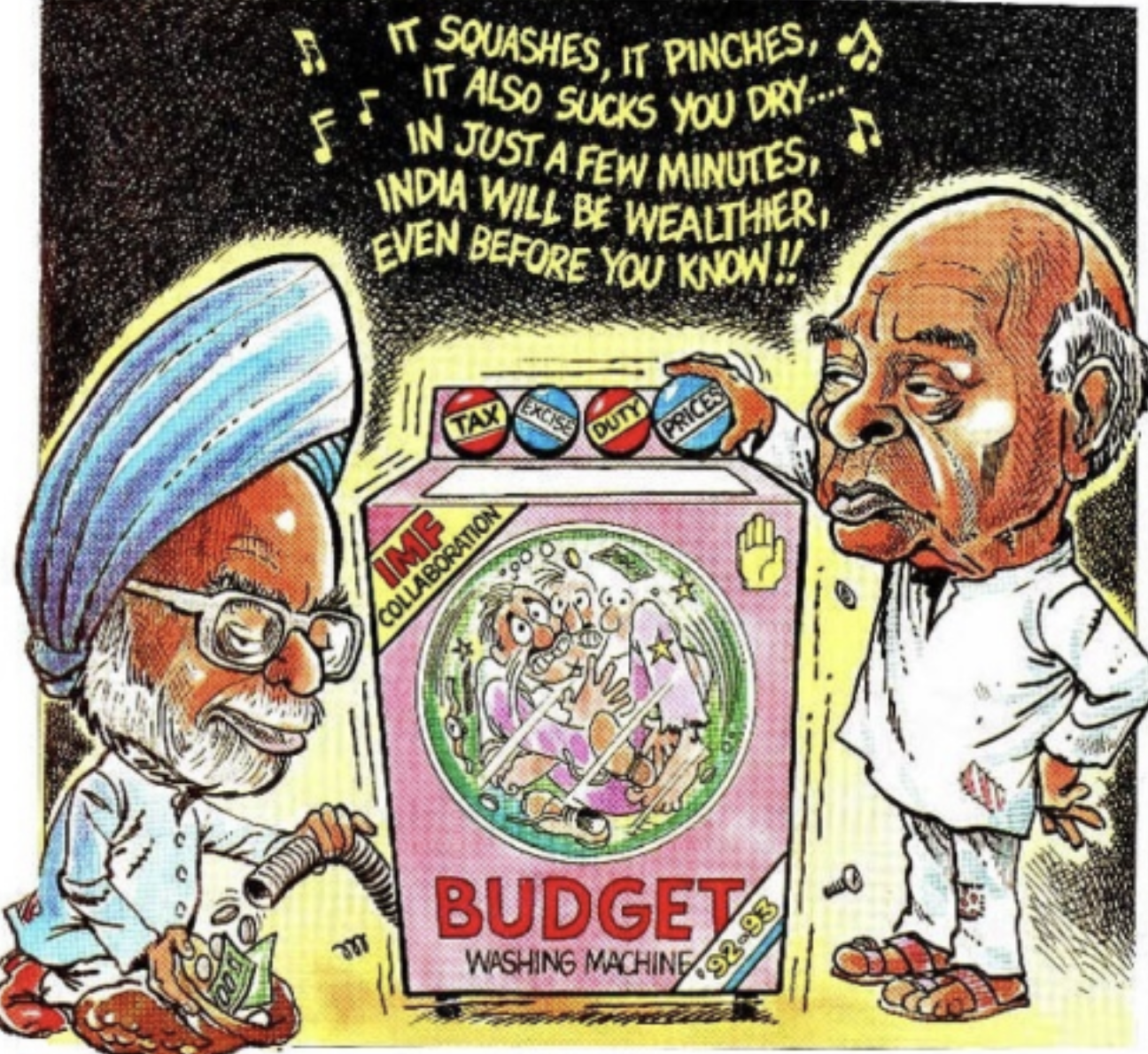

Manmohan Singh’s pivotal 1991 and 1992 budget speeches are particularly memorable examples of an annual tradition known as “Budget Day”. Each February, India’s finance minister is expected to observe a series of quirky rituals – including serving a giant pan of halwa (a sugary dessert) to his officials and posing for photographs clutching a briefcase on the steps of parliament – before reading a speech (typically laden with literary references) that outlines the government’s economic plans. In the weeks preceding Budget Day, business news channels do their best to build anticipation with sensationalist special programming in which talking heads breathlessly speculate about the budget’s potential impacts on taxpayers, investors, and companies.61

The NEP initially faced tremendous resistance from a “divided parliament, nervous industrialists, shrill intellectuals, and a stodgy, statist Congress party”.36 Despite the slow-motion collapse of the U.S.S.R. and the by-then clear success of China’s market-oriented policies, most of India’s politicians seemed “unaware of how much of an anomaly” their country had become.5 Opposition leaders denounced the “bitter pills” of currency devaluation, deregulation, and other previously unthinkable reforms62 as a surrender to the “dictates” of international financial institutions.63 Senior officials from Rao’s own party accused his government of compromising India’s sovereignty and betraying Nehru’s legacy, and “beseeched Sonia [Gandhi] to take over Congress and rescue the country.”64

Rao successfully neutralized these simplistic and predictable attacks – which had deterred previous administrations from even proposing contentious policy changes – with a slick combination of political browbeating and public relations. He jolted his opponents within Congress into submission by threatening to replace the party’s system of patronage with competitive primaries.64 Meanwhile, he and Singh nimbly recast the reform program from “a matter of compulsion” imposed by Western institutions to “a matter of conviction” borne out of Indians’ own confidence in the value and necessity of tough changes.50

While acknowledging that the reforms had an external catalyst (i.e., the IMF), Rao and Singh were careful to present the NEP as an Indian-made package – built on the foundations laid by Nehru and the Gandhis, consisting largely of policies that the Congress party had publicly endorsed in its 1991 election manifesto, and implemented on India’s own initiative (albeit with the understanding that it was a necessary precondition for assistance).66

Taking advantage of his reputation as an elder statesman unassociated with the Congress party’s “pro-business” wing, Rao deliberately avoided championing free market policies as an end unto themselves, instead deftly characterizing liberalization as being “of value to the nation”.50 Citing the need to “attain an adequate technological and competitive edge in a fast changing global economy”,4 Rao and Singh portrayed the NEP and subsequent reforms as a course correction en route to Nehru’s vision of economic independence,67 with access to foreign capital, technology, and export markets substituted for “self-reliance”.68

“Berlin Walls are collapsing all around us, and at such a time to stick to ideas and ideologies of the 1960s does not show us to be radical, but reactionary.”69

Industrialist J.R.D. Tata writing in The Times of India, August 1, 1991

Rao and Singh sustained a near-daily pace of policy announcements, speeches, and press conferences in a calculated attempt to keep the opposition “off balance.”70 Rao employed agents from the Intelligence Bureau (India’s equivalent of the FBI) to spy on Sonia Gandhi and other senior Congress party members, and used the resulting scuttlebutt regarding their views on economic reforms to prioritize certain policies while quietly shelving other controversial proposals (e.g., full privatizations of government-owned firms) that risked provoking too much of a backlash from powerful constituencies.36 Meanwhile, Singh slipped into the first package of reforms a provision – the removal of duties on newsprint – designed to keep India’s rowdy media “on side”.71

In the end, the root cause and severity of the circumstances in which India found itself in 1991 limited Rao’s opponents’ options for derailing the reform process. With airlifts of the central bank’s gold still on the front pages, even critics of the government’s specific reform plans were forced to acknowledge that the country’s own past policy choices had left India with a binary choice between taking some form of corrective action and an alternative – an unprecedented default on its sovereign debt – that “would be a recipe for long-term disaster.”47

In the absence of exogenous shocks such as droughts, wars, or spikes in the price of oil, India could arguably have muddled through each its pre-1991 crises. Whereas misguided policy had exacerbated those emergencies, 1991 saw a “policy-induced crisis par excellence”, in which the country had sunk into an unsustainable debt trap long before external developments cut short politicians’ room for maneuver.72

Although the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait and slowdowns in export markets hastened the day of reckoning, it is clear that policies pursued throughout the 1980s – in particular, increasingly reckless public spending – were untenable “and would have resulted in a crisis at some point, perhaps a little later in the 1990s.”73

The “euphoric” response to the NEP from news outlets and the public convinced Rao that “the people were […] ahead of the politicians in wanting reform.”40 The government proceeded to implement a sweeping set of transformative policies – from a restructuring of the telecommunications industry to an overhaul of capital markets regulation – that went far beyond the boilerplate terms laid out by the IMF and the World Bank (which joined the structural adjustment program in December 1991),8 and continued even after the formal expiration (in late 1993) of India’s arrangements with both institutions.74

In February 1992, Manmohan Singh used his next budget presentation – the first in India’s history to be televised live – to unveil another round of dramatic changes. These included abolishing the Controller of Capital Issues (the Delhi-based bureaucracy that arbitrarily set the valuations at which companies could go public), establishing a roadmap for making the rupee fully convertible, permitting the entry of new private-sector banks, reducing the share of banks’ deposits that had to be invested in government bonds, and directing the recently-formed Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) to institute a set of rigorous regulations aimed at protecting investors and improving transparency.75

Proclaiming that “[w]e must not remain permanent captives of a fear of the East India Company, as if nothing has changed in the past 300 years”, Singh announced that foreign institutions would be permitted to invest in Indian equities. Asserting that Indian industry was capable of going head-to-head against foreign competitors “on its own terms”, he threw open India’s doors to multinational companies.76 Foreign investment surged from a meager $80 million in 1991 to $6.4 billion just three years later.77 By mid-1993, the country was attracting enough private capital that it “had no further need to borrow” from the IMF or World Bank.78

In November 1992, the government backed the creation of a new equity exchange – the National Stock Exchange (NSE) – to compete with the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE), a storied institution that had been reduced by decades of financial repression to an inefficient, high-cost monopoly.79 Within a year of commencing operations in late 1994, turnover on the NSE’s state-of-the-art, transparent platform surpassed that of the BSE. Along with a third government-promoted institution (the National Securities Depository, established in 1996 as the country’s first electronic securities clearing house), the SEBI and the NSE facilitated the formation of dynamic, reliable capital markets capable of supporting the growth of Indian companies in the years ahead.80

In March 1993, the RBI shifted from pegging the rupee to a basket of currencies to the current managed float exchange rate system. By August 1994, the government made the rupee fully convertible for current account transactions – removing all remaining restrictions on importers’ ability to convert rupees into foreign currencies, giving businesses free rein to pay for imports or fund expansions outside India, and enabling foreign investors to repatriate their capital on demand.79

A key common factor across every modern balance of payments crisis, from India (1991) to Mexico (1994) to the East Asian economies (1996), was a fixed exchange rate system that pegged each country’s currency to the dollar (or a basket of reserve currencies) – thereby preventing exchange rate adjustments that might have corrected the mismatch between each country’s current account deficit and its financial account surplus before it provoked a crisis.82

Under the managed float system it has employed since 1993, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) continues to intervene in the foreign exchange market, but allows the rupee to fluctuate in response to market forces. Crucially, the RBI permits the currency to depreciate to help contain current account deficits; its intervention in the foreign exchange market has to date

focused on curbing excessive rupee appreciation.

For more detail on the relationship between a country’s balance of payments and its exchange rate system, as well as the process by which central banks such as the RBI intervene in forex markets, please refer to the appendix on page 20 of part one of this series (“India before 1991: tiger caged”).

India’s recovery from the crisis took less than two years – the fastest turnaround in the history of IMF structural adjustment programs.83 As the efficacy of the NEP and subsequent reforms became increasingly apparent, they gained the backing of an overwhelming majority in parliament – winning approval not only from Rao’s own party, but also from the BJP (the largest opposition party), which noisily qualified its support by declaring that the reforms were BJP ideas that Congress “had appropriated”.39 Bolstered by the economy’s unexpectedly rapid resurgence, Rao became the first Indian prime minister outside of the Nehru Gandhi dynasty to complete a full five-year term.84

The reforms galvanized by the 1991 crisis “unleashed an explosion of pent-up commercial energy”,85 transforming India’s economy from an inward-looking laggard dominated by public-sector firms into a major beneficiary of globalization led by private enterprises, exports, and foreign investment. Though less dramatic than the collapse of communism in Europe, India’s liberalization instantly reshaped the lives of nearly 900 million people – more than double the population of the entire Soviet bloc.86

The removal of red tape that had acted as a barrier to new entrants resulted in a flood of new competitors “across virtually all industries” following liberalization.87 More new businesses were registered from 1992 through 1995 than during the entire preceding decade.88 Over that same four-year period, the number of publicly-traded Indian companies more than doubled (to over 5,000),89 driven in part by the availability of foreign capital – which allowed upstarts to raise the funds necessary to compete with the country’s established, cash-rich conglomerates in capital-intensive sectors such as cellular telecoms.8 Cumulatively over the first three years following the crisis (from 1992 through 1994), India attracted more foreign direct investment than it had over the preceding three decades.90

The sheltered monopolies and cartels that had dominated India’s economy up until 1991 feared that they would lose out from reforms – particularly the Rao government’s moves to slash tariffs, abolish the import licensing regime, and allow multinationals back into the country.91 In 1993, a group of tycoons who came to be known as the “Bombay Club” wrote a letter to Manmohan Singh complaining, among other things, about the rapid reduction in import duties and the difficulty of competing with multinational corporations’ production efficiencies and “marketing shenanigans”.92 The Bombay Club’s unofficial spokesman, the head of Pune based Bajaj Auto,93 warned that Indian industry was at risk of being “wiped out”.63

Dispelling such fears, Indian businesses have thrived since 1991. Forced to compete with the world’s best, home-grown companies discovered that they could – not only in India, but in markets worldwide. Before liberalization, India manufactured fewer than 2 million motorbikes annually. Now it produces ten times that number, including over 2 million for export.94 The domestic market, which had been dominated by Japanese imports, was rapidly taken over by none other than Bajaj Auto.8

India’s auto industry comprises not only producers of cars and trucks, but also manufacturers of “two-wheelers” (motorbikes, scooters, and mopeds) and “three-wheelers” (auto rickshaws). There are over five times as many motorized two-wheelers on the country’s roads as there are cars.95

Many Indian businesses have become multinationals themselves. In a post colonial role reversal, the Tata Group is now the biggest private-sector employer in the United Kingdom.96 Pune-based Bharat Forge has grown into the world’s top supplier of metal forgings.97 Indian-owned ArcelorMittal is the globe’s leading steel producer.85 Mumbai-based Sun Pharma is among the largest manufacturers of generic drugs. Delhi-based Bharti Airtel is the dominant wireless carrier across much of sub-Saharan Africa.98

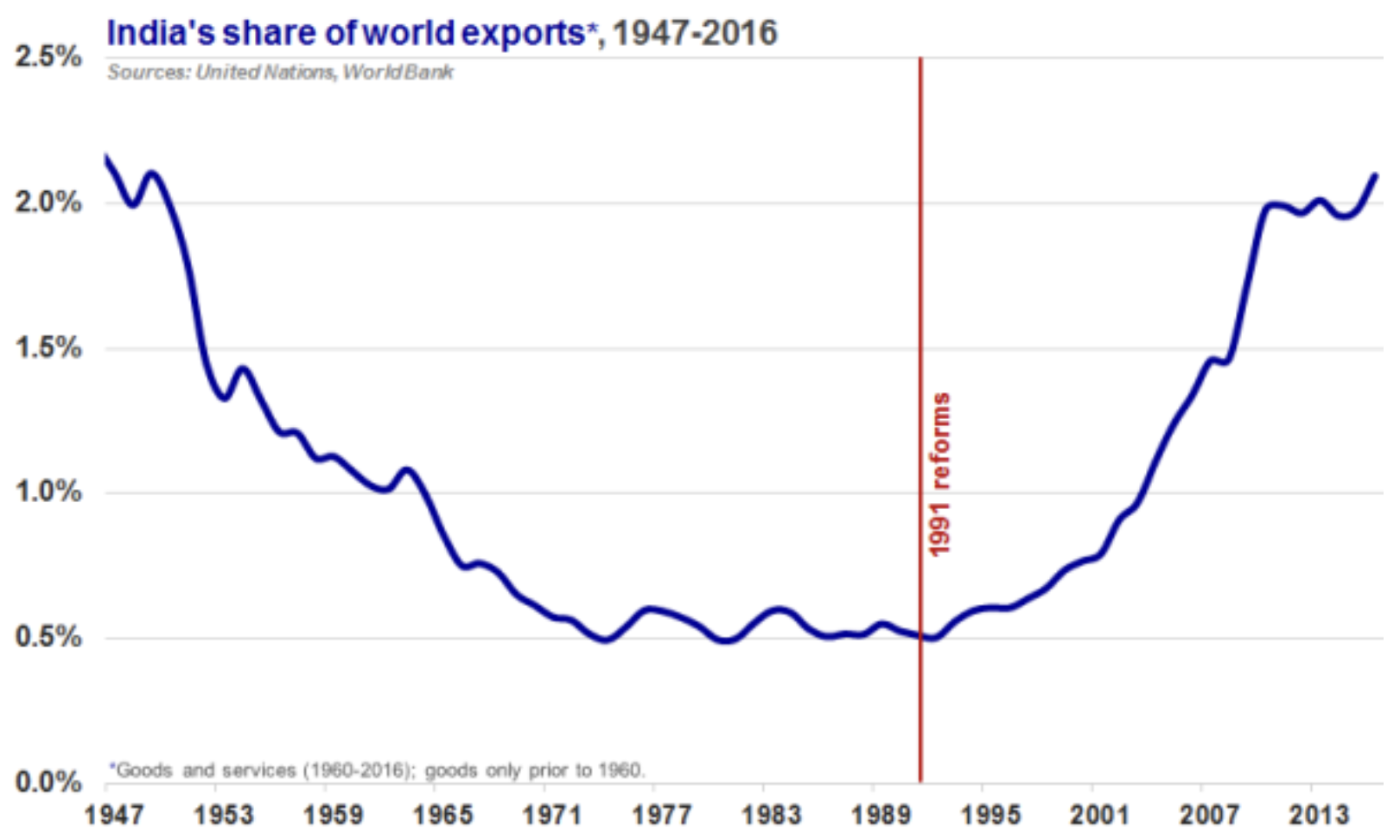

Before liberalization, an over-valued rupee and counter-productive import substitution policies held back the competitiveness of Indian exports. The 1991 currency adjustment and subsequent lowering of protectionist barriers allowed firms to make the most of India’s plentiful comparative advantages – from its abundance of technically adept, English-speaking talent to its position as the lowest-cost producer of most cotton textiles.99 During the 1990s, India’s export volumes rose at almost double the highest rate achieved in any prior decade.73 Over the past quarter-century, India’s exports have grown by a factor of twenty – fully reversing the decline in the country’s share of world exports between independence (1947) and 1991.100

The connection between trade and investment liberalization and the post-1991 acceleration in India’s economic growth is clear.102 The availability of new inputs and higher-quality, lower-cost substitutes for domestically-produced intermediate goods gave rise to entirely new products and industries. One-quarter of the increase in India’s exports during the 1990s was driven by products that had not been produced prior to the reforms.103 Access to foreign-made capital goods, along with “spillover effects” from foreign technology firms rushing to take advantage of India’s skilled workforce, spurred the country’s emergence as a global hub for software development, business process outsourcing, and pharma manufacturing. These new industries created tens of millions of well-paying jobs, not only at Indian companies such as Infosys and Wipro, but also with multinationals such as IBM – which now employs more workers in India than in the United States.104

Leveraging their experience dealing with inadequate infrastructure, erratic bureaucrats, and a demanding but thrifty home market, Indian firms have become the world’s leading “frugal innovators” – using scrappy design to put “first-world” products within reach of billions of lower-income consumers. Mumbai-based Godrej Group combined high-end insulation and a computer fan to create the “Little Cool”: a ₹3,250 ($50) refrigerator that runs on a 12-volt battery.105 General Electric’s Indian subsidiary invented a ₹25,000 ($386) portable electrocardiograph (ECG) device that is now exported to emerging markets around the globe.106

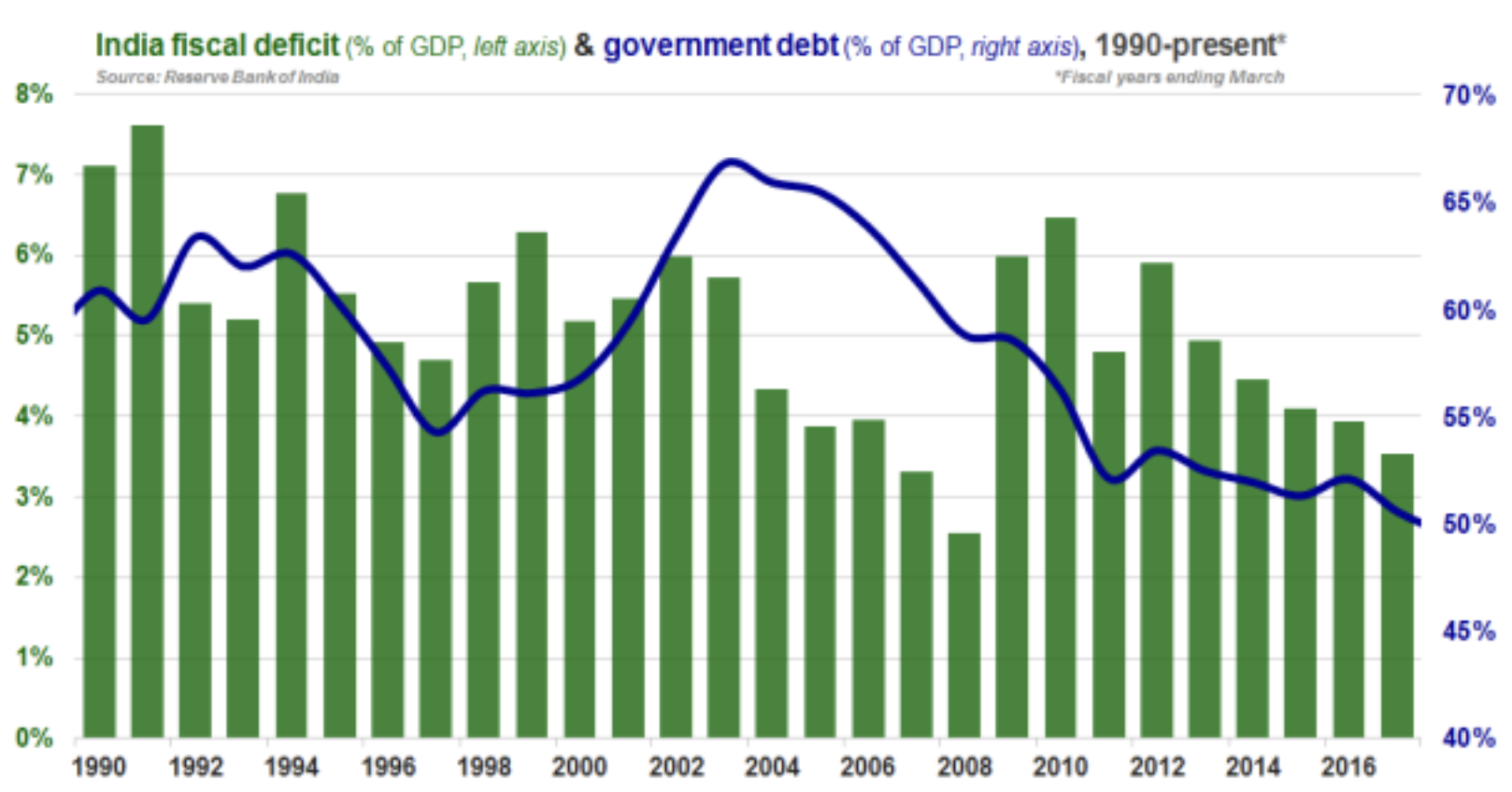

Led by a reinvigorated private sector, booming exports, and surging foreign investment, India’s economy has expanded nine-fold in the quarter-century since Manmohan Singh quoted Victor Hugo before parliament.107 The country’s share of world stock market capitalization has more than quintupled, to 2.4%,108 while the government’s fiscal deficit (as a percentage of GDP) has been halved.109 Private-sector investment has doubled as a share of GDP, to 24%.110 The number of motor vehicle-owning households has increased more than eleven-fold.111 Since 1992, when the end of state-owned Air India’s monopoly gave rise to the country’s first private airlines, India’s air passenger traffic has ballooned by a factor of twelve.112 In 1991, Indians faced a three-year waiting list to get a landline connection. Today, the country has over one billion mobile phone subscribers.113

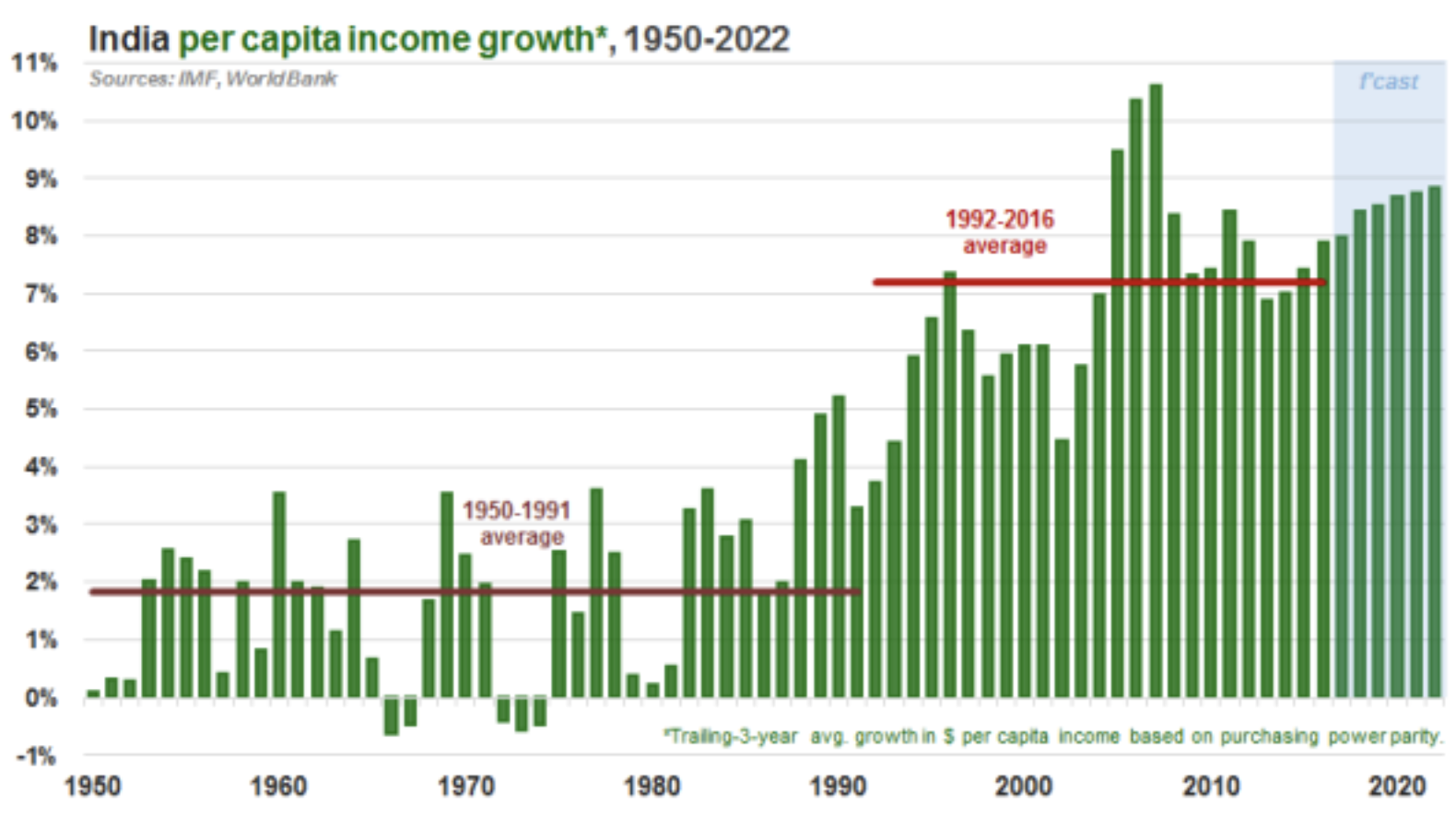

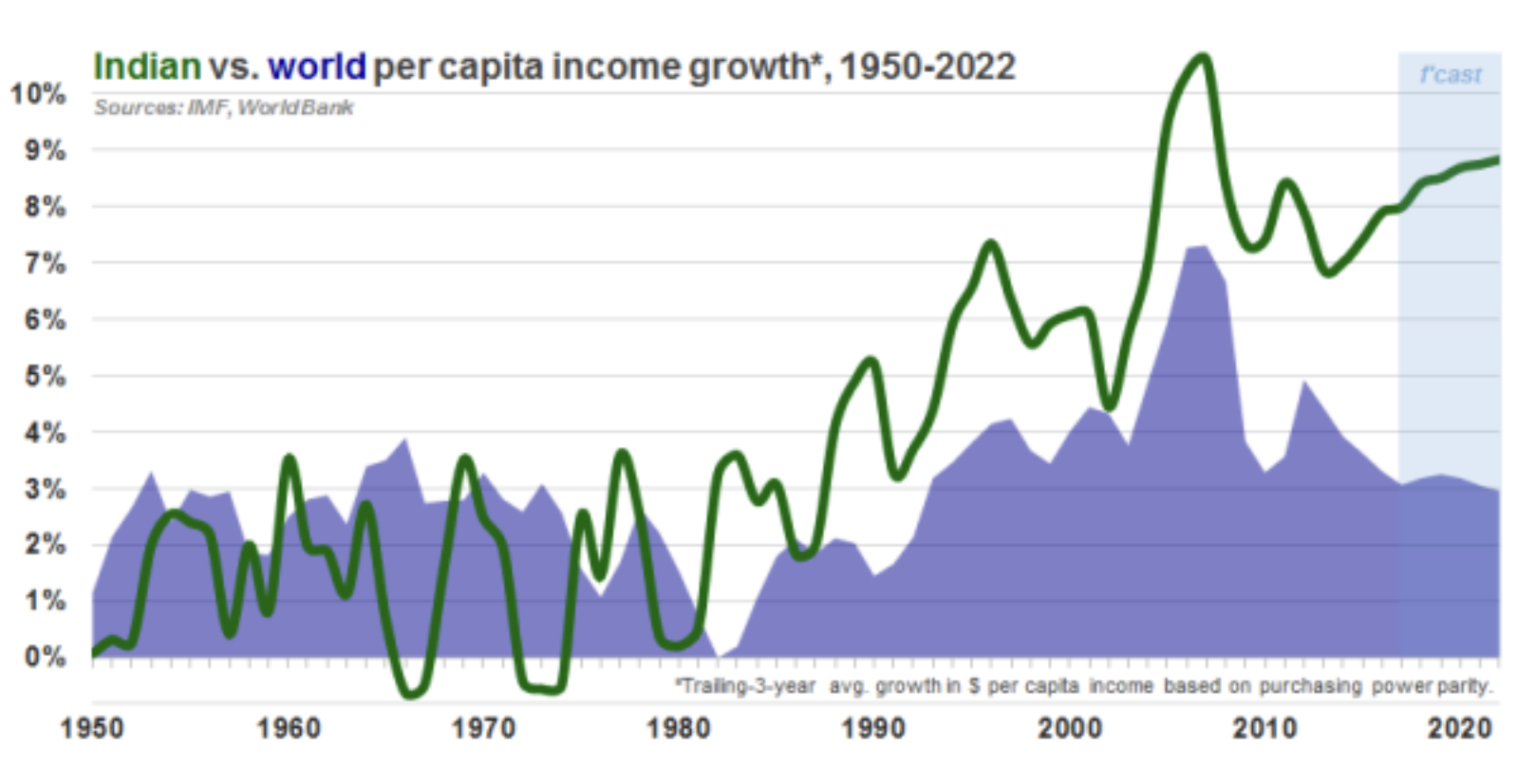

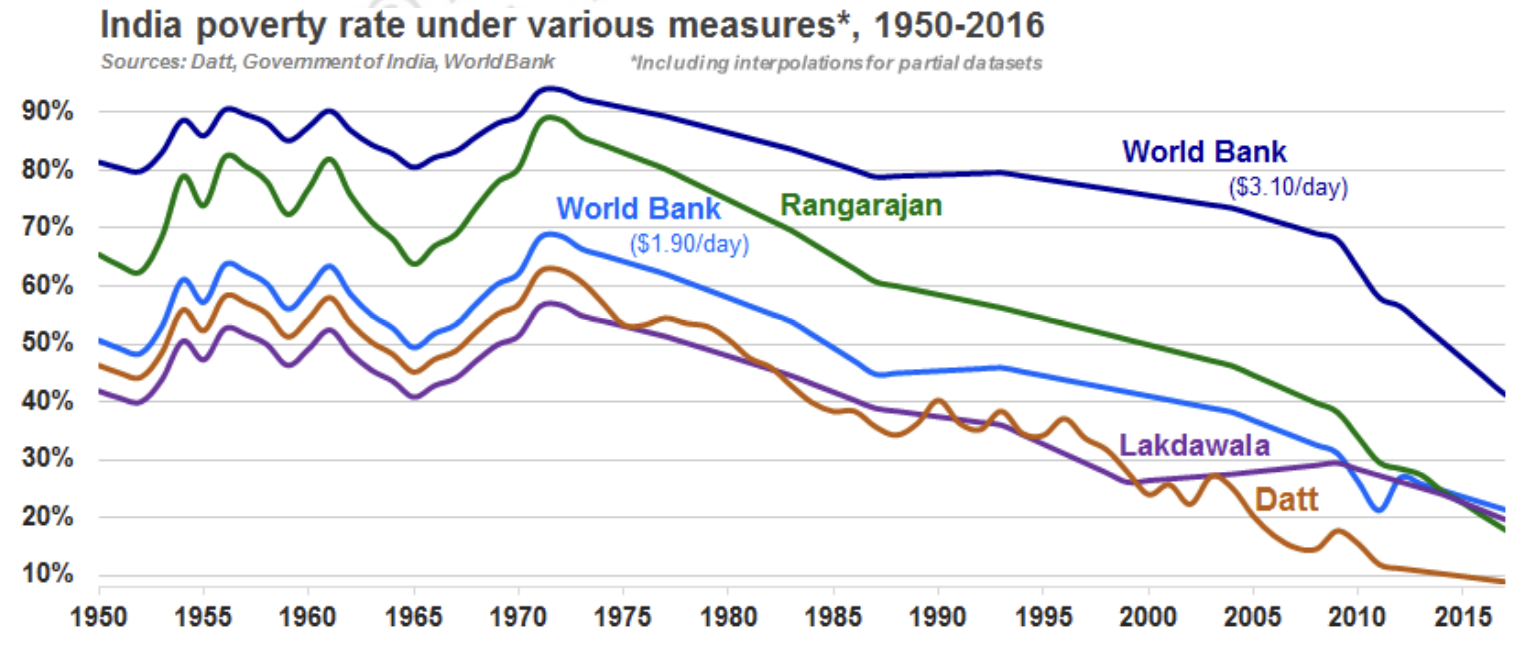

Since 1991, India’s per capita income has grown more than three times faster than in the decades that preceded liberalization. Refuting the notion of a so-called “Hindu rate of growth”, increases in the country’s per capita income have surpassed global per capita GDP growth by a large and expanding margin, outpacing the rest of the world during booms as well as in the midst of global downturns.114 Belying critics who claimed that reforms would only benefit the rich, the proportion of India’s population living in poverty has been cut in half.115

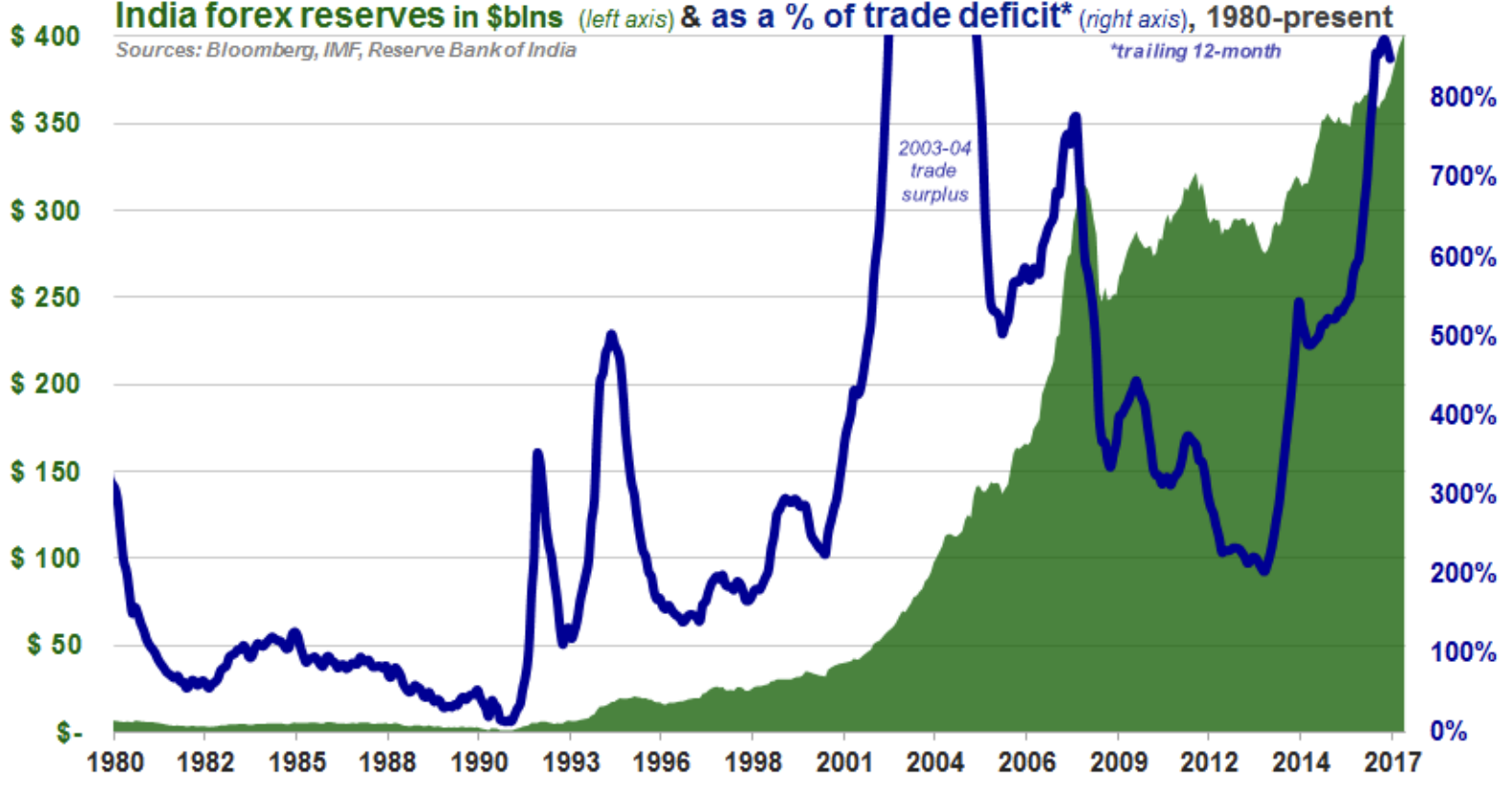

India’s decision to open up to foreign trade, capital, and technology has strengthened its financial resilience and stability. The country’s exports of information technology and other services have climbed from virtually nothing in 1991 to over $160 billion (as of 2016),116 helping to offset its merchandise trade deficit. The dramatic decline in oil prices since 2014 – coupled with the government’s canny decision to take advantage of the price drop to eliminate costly fuel subsidies – allowed India to narrow its current account deficit to just 0.5% of GDP last year.16

More importantly, India now attracts enough “sticky”, un-borrowed sources of capital to reliably fund much wider current account deficits, if necessary – allowing the country to calmly surmount oil price surges akin to the one that heralded its 1991 balance of payments crunch.117 Cumulatively over the past two decades, the amount of foreign direct investment that has flowed into India has covered its trade deficit more than twice over.118

Furthermore, by intervening in the currency market during periods in which the net inflow of capital into India (i.e., the country’s financial account surplus) has exceeded the amount necessary to fund its current account deficit,119 the RBI has been able to amass forex reserves of over $400 billion – enough to cover India’s annual trade deficit more than eight times over.27

The 1991 crisis triggered reforms that – despite the Rao government’s carefully worded homages to India’s erstwhile leaders – effectively repudiated Nehru’s vision of India as an autarkic, state-dominated oasis of self-reliance. Yet those same reforms have brought India closer than ever to Nehru’s goal of “economic independence”. Formerly a supplicant to international development agencies, India is now a net donor of foreign aid.120 Once dependent on food assistance, India is now the world’s largest rice exporter.121 India repaid its last IMF loans in 2000, and has been a creditor of the Fund since 2003.122 In 2005, a quarter of a millennium after the first parts of India came under the dominion of the East India Company, its trademarks and other assets were acquired – by an Indian entrepreneur.123 In 2009, the RBI triumphantly purchased 200 tons of gold from the IMF – triple the quantity it had been forced to pawn during the 1991 crisis.124

In a 1995 lecture at Columbia University, Manmohan Singh declared that India’s “tryst with globalization had become irreversible”.8 He has been proven right, as every successive government since the crisis has kept India on the path of reform, varying only “in terms of speed and emphasis.”125 Nevertheless, India’s liberalization is a “half-finished revolution”: the country’s dynamic economy now churns out world-class companies and engineers, but its average citizen is more likely to be connected to a mobile broadband network than to a sewer.126 A future series of dispatches will delve deeper into the ways in which the economic reform unleashed in 1991 remains a work in progress, and will examine the tools available to policymakers seeking to realize the half-fulfilled promise of 1991.

* * *

Andrei Stetsenko

October 31, 2017

Legal Information and Disclosures

The views expressed are the views of the author as of the date indicated on each posting; such views are subject to change without notice. Farley Capital L.P. (Farley Capital) has no duty or obligation to update the information contained herein. Further, Farley Capital makes no representation, and it should not be assumed, that past investment performance is an indication of future results. Any discussion regarding investment returns or financial projections are provided as illustrative examples only and no inference shall be made therefrom regarding the potential for returns on any investment discussed. Moreover, you should be aware that all types of investments involve a significant degree of risk, and wherever there is potential for profit, there is also the possibility of loss.

This content is being made available for informational and educational purposes only and should not be used for any other purpose. The information contained herein does not constitute and should not be construed as financial, legal, or tax advice, or as an offering of advisory services. The information contained herein shall not constitute an offer to sell, or a solicitation to subscribe for, interests in any investment vehicle managed by Farley Capital, which offer or solicitation will only be made to qualified investors and accompanied by a private placement memorandum, subscription agreement, and other related offering documents. Certain information contained herein concerning economic trends and performance is based on or derived from information provided by independent third-party sources. Farley Capital believes that the sources from which such information has been obtained are reliable; however, it cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of such information and has not independently verified the accuracy or completeness of such information or the assumptions on which such information is based.

This content, including the information contained herein, may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted in whole or in part, in any form without the prior written consent of Farley Capital.

References and Notes

1 Aiyar, Swaminathan. “25 years of economic reforms: From super-beggar to potential superpower” (July 2016). The Economic Times. Retrieved from http://blogs.economictimes.indiatimes.com/ Swaminomics/25-years-of-economic-reforms-from-super-beggar-to-potential-superpower/ 2 The Economist (October 2010). Issue 397:8702, cover page. Retrieved from

https://www.nypl.org/collections/articles-databases/economist-historical-archive-1843-2008 3 In the decade leading up to 1991, many Indians took notice of the early success of economic reforms in Deng Xiaoping’s China and “the inability of the Soviet system to meet even its food requirements”. Nevertheless, India’s democratic system meant that it was politically tougher for its leaders during the 1980s, Indira Gandhi and her son Rajiv, to dismantle the Nehruvian economic system than it had been for China’s Deng Xiaoping to undo the legacy of Mao. Rodrik, Dani and Subramanian, Arvind. “From ‘Hindu Growth’ To Productivity Surge: The Mystery of the Indian Growth Transition” (March 2004). National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 10376. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w10376.pdf; Mukherji, Rahul. “The State, Economic Growth, and Development in India” (February 2009). India Review, 8:1, pages 81-106. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14736480802665238

4 Singh, Manmohan. “Budget 1991-92 Speech” (July 1991). Government of India, Ministry of Finance. Retrieved from http://indiabudget.nic.in/bspeech/bs199192.pdf

5 Crook, Clive. “A Survey of India: Small world” (May 1991). The Economist, 319:7705, pages 139- 142. Retrieved from https://www.nypl.org/collections/articles-databases/economist-historical archive-1843-2008

6 Boughton, James M. Tearing Down Walls: The International Monetary Fund, 1990-1999 (February 2012), Chapter 9: Five Fat Years: Recovery from the Debt Crisis, 1990-94. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/history/2012/pdf/c9.pdf

7 Vikraman, Shaji. “The years of V P Singh, and the start-stop push to reforms” (April 2017). Indian Express. Retrieved from http://indianexpress.com/article/explained/the-years-of-v-p-singh-and-the start-stop-push-to-reforms/

8 Mukherji, Rahul. “The State, Economic Growth, and Development in India” (February 2009). India Review, 8:1, pages 81-106. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14736480802665238 9 Bazliel, Sharla. “The inheritance of a loss” (February 2014). India Today. Retrieved from http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/john-elliott-describes-congress-descent-into-chaos/1/343524.html 10 Raghavan, Srinivasa. “1991: The Real Villain Was Rajiv Gandhi, The Real Hero Was Not Manmohan” (July 2016). Swarajya. Retrieved from https://swarajyamag.com/politics/1991-the-real villain-was-rajiv-gandhi-the-real-hero-was-not-manmohan

11 Prakash, B. A. The Indian Economy Since 1991 (2009), Chapter V: External Sector. Pearson Education India. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=gDjiQIU9QvUC 12 Bloomberg L.P. Bloomberg Crude Oil Historical Price. Retrieved from Bloomberg terminal, OILPHIST Index

13 Cerra, Valerie and Saxena, Sweta C. “What Caused the 1991 Currency Crisis in India?” (October 2000). International Monetary Fund, Working Paper 00/157. Retrieved from

http://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/30/What-Caused-the-1991-Currency-Crisis in-India-3794

14 Pareek, Shreya. “Did You Know That The Largest Air Evacuation In History Was Done By India?” (February 2015). The Better India. Retrieved from http://www.thebetterindia.com/15179/heres need-know-largest-air-evacuation-history-india/

15 International Monetary Fund. IMF India BOP Current Account Exports Goods (2016). Retrieved from Bloomberg terminal, 5341R007 Index; International Monetary Fund. IMF India BOP Current Account Imports Goods (2016). Retrieved from Bloomberg terminal, 5341R008 Index

16 International Monetary Fund. BOP6 India Current Account Total Net USD (2016). Retrieved from Bloomberg terminal, BCA6B534 Index

17 Nair, Vijay. Published in Chari, Mridula, “In photos: The Air India staff behind Ashkay Kumar’s ‘Airlift’” (January 2016). Scroll.in. Retrieved from https://scroll.in/article/802539/in-photos-the-air india-staff-behind-akshay-kumars-airlift

18 IMF member countries contribute funds through a quota system. The Fund’s policies allow a member to draw 25% of its quota without specifying forward-looking policy commitments. Boughton, James M. Tearing Down Walls: The International Monetary Fund, 1990-1999 (February 2012), Chapter 9: Five Fat Years: Recovery from the Debt Crisis, 1990-94. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/history/2012/pdf/c9.pdf

19 Acharya, Shankar. “India: Crisis, Reforms and Growth in the Nineties” (July 2002). Stanford University, Center for International Development, Working Paper 139. Retrieved from http://globalpoverty.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/139wp.pdf

20 Hazarika, Sanjoy. “Rival of Singh Becomes India Premier” (November 1990). The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1990/11/10/world/rival-of-singh-becomes-india premier.html

21 Baru, Sanjaya. “It was 25 years ago today…” (July 2017). The Economic Times. Retrieved from http://blogs.economictimes.indiatimes.com/et-commentary/it-was-25-years-ago-today/ 22 Crossette, Barbara. “India in an Uproar Over Refueling of U.S. Aircraft” (January 1991). The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1991/01/30/world/india-in-an-uproar-over refueling-of-us-aircraft.html

23 Boughton, James M. Tearing Down Walls: The International Monetary Fund, 1990-1999 (February 2012), Chapter 9: Five Fat Years: Recovery from the Debt Crisis, 1990-94. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/history/2012/pdf/c9.pdf 24 Aiyar, Shankkar. “Memories of 1991: The final months before the Indian economy was finally unshackled” (July 2016). Quartz. Retrieved from https://qz.com/721742/memories-of-1991-the final-months-before-the-indian-economy-was-finally-unshackled/

25 Crook, Clive. “A Survey of India: Expedite” (May 1991). The Economist, 319:7705, page 154. Retrieved from https://www.nypl.org/collections/articles-databases/economist-historical-archive 1843-2008

26 Chowdhury, Jayanta R. “Lessons from a tale of two rupee devaluations” (June 2013). The Telegraph. Retrieved from http://www.telegraphindia.com/1130624/jsp/business/story_17040688.jsp 27 International Monetary Fund. India Reserve Foreign Exchange Holdings (August 2017). Retrieved from Bloomberg terminal, 534.055 Index

28 The Times of India News Service. “BJP, CPM lambast Cong. manifesto” (April 1991). The Times of India. Retrieved from https://www.nypl.org/collections/articles-databases/times-india-1838-2003 29 The New York Times. “20 Tons of Gold Sold by India” (June 1991). Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1991/06/07/business/20-tons-of-gold-sold-by-india.html

30 The Economist. “Why do Indians love gold?” (November 2013). Retrieved from

https://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2013/11/economist-explains-11 31 Bloomberg L.P. Republic of India – Standard & Poor’s Sovereign Credit Rating (LT Debt).

Retrieved from Bloomberg terminal, 1504Z IN [Equity] CRPR

32 Guru, Sutanu. “25 Years Of Reforms: What Really Happened in July 1991” (January 2016). Business World. Retrieved from http://businessworld.in/article/25-Years-Of-Reforms-What-Really Happened-In-July-1991/14-01-2016-90232/

33 Lulla, Anil B. “How a forgotten ex-PM paved the way for entrepreneurship in India” (January 2017). YourStory. Retrieved from https://yourstory.com/2017/01/p-v-narasimha-rao-half-lion startup-lesson-25-years-ago/

34 Aiyar, Shankkar. “Wholesale Politics, Retail Reforms Define Post 1991 India” (July 2016). Retrieved from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/wholesale-politics-retail-reforms-define-post-1991- india-aiyar

35 Doctor, Vikram. “25 Years Of Reforms: PV Narasimha Rao, the man of that moment” (July 2016). The Economic Times. Retrieved from http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and nation/25-years-of-reforms-pv-narasimha-rao-the-man-of-that-moment/articleshow/53308599.cms 36 Biswas, Soutik. “Reassessing India's 'forgotten prime minister'” (July 2016). BBC News. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-36791913

37 Ray, Sanjana. “Remembering PV Narasimha Rao, ‘modern-India’s Chanakya’, on his 96th birthday” (June 2017). YourStory. Retrieved from https://yourstory.com/2017/06/narsimha-rao legacy/

38 Rao had been planning on retiring; in fact, his belongings had been in the process of being packed up so that he could depart New Delhi immediately following the election. Weinraub, Bernard. “MAN IN THE News; Congress Party's Calculating Loyalist: Pamulaparti Venkata Narasimha Rao” (June 1991). The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1991/06/22/world/man congress-party-s-calculating-loyalist-pamulaparti-venkata-narasimha-rao.html; Malhotra, Inder. “Rear View: How Narasimha Rao became PM” (April 2015). Indian Express. Retrieved from http://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/rear-view-how-narasimha-rao-became-pm/ 39 Krishna, Ananth V. India Since Independence: Making Sense of Indian Politics (August 2010). Pearson Education India. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=8v7Vr2iQUHkC 40 Das, Gurcharan. India Unbound (April 2002), Chapter 15: The Golden Summer of 1991. Anchor Books.

41 Datta-Ray, Sunanda K. “PV Narasimha Rao: The Saga of the Southerner” (October 2016). OPEN Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.openthemagazine.com/article/essay/pv-narasimha-rao the-saga-of-the-southerner

42 Puljal, Abhilash. “Book Review: Half Lion: How P.V. Narasimha Rao transformed India by Vinay Sitapati” (August 2016). London School of Economics, South Asia @ LSE blog. Retrieved from http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/southasia/2016/08/03/book-review-half-lion-how-p-v-narasimha-rao transformed-india-by-vinay-sitapati/

43 Harikrishnan, Charmy. “25 years of reforms: How a PM with zero knowledge of economics scripted India’s biggest turnaround story” (July 2016). The Economic Times. Retrieved from http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/25-years-of-reforms-how-a-pm-with zero-knowledge-of-economics-scripted-indias-biggest-turnaround-story/articleshow/53309051.cms 44 Sitapati, Vinay. Half Lion: How P.V. Narasimha Transformed India (June 2016). Penguin Books. Excerpt retrieved from https://www.foundingfuel.com/article/the-man-who-knew-tomorrow/ 45 Baru, Sanjaya. 1991: How P.V. Narasimha Rao Made History (September 2016). Aleph Book Company. Excerpt retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.in/sanjaya-baru/pv-narasimha-rao-not manmohan-singh-paved-the-way-for-indias_a_21576432/

46 Masoodi, Ashwaq. “Forget more big bang reforms, fix small things: Jairam Ramesh” (April 2016). Livemint. Retrieved from http://www.livemint.com/Politics/ZcrGcIo2xQvBOGJCuTkd6O/Forget more-big-bang-reforms-fix-small-things-Jairam-Rames.html

47 Aiyar, Shankkar. Accidental India: A History of the Nation's Passage Through Crisis and Change (October 2012). Aleph Book Company. Excerpt retrieved from http://www.firstpost.com/living/how rao-made-manmohan-indias-accidental-reformer-468707.html

48 Williamson, John. “The Rise of the Indian Economy” (May 2006). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, American Diplomacy. Retrieved from

http://www.unc.edu/depts/diplomat/item/2006/0406/will/williamson_india.html

49 Kalra, Mahesh A. “25 Years of India’s Economic Reforms: A Story of Triumphs and Losses” (October 2016). DNA India. Retrieved from http://www.dnaindia.com/money/report-25-years-of india-s-economic-reforms-a-story-of-triumphs-and-losses-2264106

50 Bamzai, Kaveree. “Inside the complex mind of India’s forgotten PM” (August 2015). India Today. Retrieved from http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/inside-the-complex-mind-of-indias-forgotten pm/1/461472.html

51 Express archive photo. Indian Express. Retrieved from http://indianexpress.com/photos/picture gallery-others/manmohan-singh-turns-83-today-here-are-some-rare-pictures-from-express-archives 3050525/3/

52 Crook, Clive. “A Survey of India: Plain tales of the license raj” (May 1991). The Economist, 319:7705, pages 145-149. Retrieved from https://www.nypl.org/collections/articles

databases/economist-historical-archive-1843-2008

53 Asthana, Vandana. Water Policy Processes in India: Discourses of Power and Resistance (September 2009), Chapter 3: The process of economic liberalization and private sector participation. Routledge. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=q0CMAgAAQBAJ 54 Other key figures behind the design and implementation of the NEP included Montek Ahluwalia, Jairam Ramesh, Shankar Acharya, and Rakesh Mohan. Ye, Min. Diasporas and Foreign Direct Investment in China and India (August 2014), Chapter 4: Deregulation without Openness in India. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=qUxsBQAAQBAJ 55 Rao, Narasimha. “The Prime Minister’s 9 July 1991 Speech” (July 1991). India Before ‘91. Retrieved from http://indiabefore91.in/node/6/submission/16

56 Bloomberg L.P. USDINR Spot Exchange Rate – Price of 1 USD in INR, Historical Data. Retrieved from Bloomberg terminal, INR Curncy

57 That month, while it awaited more help from the IMF, Rao’s administration was forced to pledge another 47 tons of gold as collateral for $405 million worth of additional loans from the Bank of England and Bank of Japan. Vikraman, Shaji. “25 years on, Manmohan Singh has a regret: In crisis, we act. When it’s over, back to status quo” (July 2016). The Indian Express. Retrieved from http://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-news-india/manmohan-singh-opening-indian-economy 1991-economic-reforms-pv-narasimha-rao-rbi-indian-rupee-devaluation-2886876; Vikraman, Shaji. “In fact: Glitter of 1993 gold scheme lay in its amnesty clause” (April 2017). The Indian Express. Retrieved from http://indianexpress.com/article/explained/in-fact-glitter-of-1993-gold-scheme-lay-in its-amnesty-clause

58 Khanna, Tarun. Interview with Suresh Krishna (December 2012). Harvard Business School, Baker Library Special Collections, Creating Emerging Markets Oral History Collection. Retrieved from http://www.hbs.edu/creating-emerging-markets/interviews/Pages/profile.aspx?profile=skrishna 59 Dasgupta, Biplab. Globalization: India’s Adjustment Experience (July 2005), Chapter 1: Introduction. SAGE Publications. Retrieved from

https://books.google.com/books?id=mpdMLKJtEAAC

60 Kapila, Uma. India’s Economic Development Since 1947 (2008), Chapter 11: Macroeconomic Stabilisation: Trade, Fiscal and Monetary Policy Issues. Academic Foundation. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=KTbA2R_6gjAC

61 Subramanian, Samanth. “Long View: The Origin of the Budget Briefcase” (March 2012). The New York Times. Retrieved from https://india.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/03/14/long-view-the-origin-of the-budget-briefcase; Chaudhary, Archana. “India’s Budget Is Seeking the Sweet Spot: QuickTake Q&A” (January 2017). Bloomberg News. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/ 2017-01-25/india-budget-seeks-sweet-spot-as-cash-grab-sours-quicktake-q-a

62 Miranda, Luis. “25 years of liberalisation and what life was like in 1991” (February 2016). Forbes India. Retrieved from http://www.forbesindia.com/blog/accidental-investor/25-years-of-liberalisation and-what-life-was-in-1991

63 Alamgir, Jalal. “Narratives of Open-Economy Policies in India, 1991–2000” (May 2007). Asian Studies Review, 31:2, pages 155-170. Retrieved from

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10357820701373309

64 Komiereddi, Kapil. “PV Narasimha Rao reinvented India – so why is he the forgotten man?” (May 2012). The National. Retrieved from https://www.thenational.ae/lifestyle/pv-narasimha-rao reinvented-india-so-why-is-he-the-forgotten-man-1.455990

65 Ninan, Ajit. “Cartoon on 1992-93 budget” (1992). India Today. Retrieved from

http://indiatoday.intoday.in/gallery/union-budget-rail-budget-petroleum-budget-sports-budget education-budget/9/14288.html

66 Singh, Manmohan. “Budget 1992-93 Speech” (February 1992). Parliament of India. Excerpt retrieved from http://parliamentofindia.nic.in/lsdeb/ls10/ses3/0329029205.htm

67 De, Rahul. “India’s Liberalisation and Newspapers: Public Discourse around Reforms” (July 2017). Economic and Political Weekly, 52:27. Retrieved from http://www.academia.edu/34264503/ Indias_liberalisation_and_Newspapers_Public_Discourse_around_Reforms

68 The Times of India News Service. “Licensing scrapped” (July 1991). The Times of India. Retrieved from https://www.nypl.org/collections/articles-databases/times-india-1838-2003 69 Tata, J.R.D. “Berlin Walls should fall” (August 1991). The Times of India. Retrieved from https://www.nypl.org/collections/articles-databases/times-india-1838-2003

70 The Economist. “Reformer Rao” (July 1991). Retrieved from

http://www.economist.com/blogs/banyan/2014/07/archive

71 The Economist. “Who put the shine into India?” (May 2004). Retrieved from

http://www.economist.com/node/2705880

72 Joshi, Vijay and Little, I.M.D. India: Macroeconomics and Political Economy, 1964-1991 (July 1994), Chapter 8: Crisis and Short-Term Macroeconomic Policy: An Appraisal. The World Bank, World Bank comparative macroeconomic studies. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/ curated/en/259451468772490617/India-Macroeconomics-and-political-economy-1964-1991 73 Krueger, Anne O. Economic Policy Reforms and the Indian Economy (July 2002), Chapter 1: The Indian Economy in Global Context. University of Chicago Press. Retrieved from

https://books.google.com/books?id=S6LZBiwmF-wC

74 World Bank, Independent Evaluation Group. “Structural Adjustment in India” (2012). Retrieved from http://lnweb90.worldbank.org/oed/oeddoclib.nsf/DocUNIDViewForJavaSearch/

0586CC45A28A2749852567F5005D8C89

75 Vikraman, Shaji. “In The steady progress of FIIs, and a continuing debate” (April 2017). The Indian Express, Express Economic History Series. Retrieved from

http://indianexpress.com/article/explained/express-economic-history-series-the-steady-progress-of fiis-and-a-continuing-debate/

76 Singh, Manmohan. “Budget 1992-93 Speech” (February 1992). Government of India, Ministry of Finance. Retrieved from http://indiabudget.nic.in/bspeech/bs199293.pdf

77 Reserve Bank of India. Balance of Payments, Foreign Investment (2017). Retrieved from Bloomberg terminal, INBQFI Index

78 Boughton, James M. Tearing Down Walls: The International Monetary Fund, 1990-1999 (February 2012), Chapter 9: Five Fat Years: Recovery from the Debt Crisis, 1990-94. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/history/2012/pdf/c9.pdf 79 Sharma, Shalendra D. China and India in the Age of Globalization (July 2009), Chapter 2: China and India Embrace Globalization. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from

https://books.google.com/books?id=3c8hAwAAQBAJ

80 Vikraman, Shaji. “NSE and NSDL: Institutions that revolutionised Indian bourses” (July 2016). The Indian Express. Retrieved from http://indianexpress.com/article/explained/manmohan-singh indian-economy-indian-rupee-devaluation-nse-nsdl-stock-exchange-bombay-stock-exchange 2924639/

81 Jnpet. “National Stock Exchange, Mumbai, India” (December 2007). Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:National_Stock_exchange_Mumbai.JPG

82 IMF papers single out the Mundell-Fleming model as the most instructive framework for understanding India’s crisis. Mundell-Fleming theorizes that in countries with low capital mobility, fiscal expansions lead to higher interest rates, higher output, and current account deficits that exceed financial account inflows. The resulting balance of payments deficit must be corrected by an exchange rate adjustment large enough to reduce the current account deficit, which (after the government finally allowed the rupee to depreciate in July 1991) is what ended up occurring in India. Cerra, Valerie and Saxena, Sweta C. “What Caused the 1991 Currency Crisis in India?” (October 2000). International Monetary Fund, Working Paper 00/157. Retrieved from

http://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/30/What-Caused-the-1991-Currency-Crisis in-India-3794

83 Pandhi, Nikhil. “‘Manmohan Singh Came To Reforms Out Of Conviction, Narasimha Rao Came To It Out Of Compulsion’: An Interview With Jairam Ramesh” (September 2015). The Caravan Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.caravanmagazine.in/vantage/manmohan-singh-reforms conviction-narasimha-rao-compulsion-jairam-ramesh

84 Datta-Ray, Sunanda K. “Meanwhile: The unsung genius of India’s reforms” (December 2004). The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2004/12/29/opinion/meanwhile-the unsung-genius-of-indias-reforms.html

85 The Economist. “Business in India: A bumpier but freer road” (September 2010). Retrieved from http://www.economist.com/node/17145035

86 United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects (2015), File POP/1-1: Annual total population (both sexes combined) by major area, region and country, 1950-2015. Retrieved from https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp

87 Mody, Ashoka, Nath, Anusha, and Walton, Michael. “Sources of Corporate Profits in India: Business Dynamism or Advantages of Entrenchment?” (July 2010). India Policy Forum, 7. National Council of Applied Economic Research (New Delhi), Brookings Institution. Retrieved from http://www.ncaer.org/publication_details.php?pID=108

88 Government of India, Ministry of Statistics & Programme Implementation. “Statistical Year Book India 2016” (December 2015), Chapter 17: Companies. Retrieved from

http://www.mospi.gov.in/sites/default/files/Statistical_year_book_india_chapters/ch17.pdf 89 World Bank. World Development Indicators (2016), World Federation of Exchanges, Listed domestic companies, total. Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/CM.MKT.LDOM.NO 90 World Bank. World Development Indicators (2016), Foreign direct investment, net inflows (BoP, current US$). Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.KLT.DINV.CD.WD; Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. “Foreign Direct Investment in India” (1996). Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote= OCDE/GD(96)169&docLanguage=En

91 Chauvin, Sophie and Lemoine, Françoise. “India in the World Economy: Traditional Specialisations and Technology Niches” (September 2003). Centre d'Etudes Prospectives et d'Informations Internationales, Working Paper No. 2003-09. Retrieved from

https://ideas.repec.org/p/cii/cepidt/2003-09.html

92 Bhandari, Bhupesh. “Once there was the Bombay Club…” (January 2013). Business Standard. Retrieved from http://www.business-standard.com/article/opinion/bhupesh-bhandari-once-there-was the-bombay-club-111070800048_1.html

93 Singh, Pragya. “The Home Alone Boys” (January 2011). Outlook Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.outlookindia.com/magazine/story/the-home-alone-boys/269748

94 Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers. “India SIAM Two Wheeler Sales Domestic & Exports” (2017). Retrieved from Bloomberg terminal, INVS2WHL Index

95 Goel, Rahul, Mohan, Dinesh. Guttikunda, Sarath, and Tiwari, Geetam. “Assessment of motor vehicle use characteristics in three Indian cities” (June 2015). Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 44, pages 254-265. Retrieved from http://www.urbanemissions.info/wp content/uploads/docs/2015-06-TRD-India-Three-Cities-Veh-Characteristics.pdf

96 Elliott, John. “Ratan Tata, the UK’s largest private sector employer, steps down” (December 2012). The Independent. Retrieved from http://www.independent.co.uk/voices/our-voices/the foreign-desk/ratan-tata-the-uks-largest-private-sector-employer-steps-down-8433061.html 97 Bobo, Jeff. “Hawkins plant purchased by world's largest metal forging company” (January 2017). The Kingsport Times-News. Retrieved from http://www.timesnews.net/Business/2017/01/26/ Hawkins-plant-purchased-by-world-s-largest-metal-forging-company

98 Onu, Emele and Alake, Tope. “Bharti Airtel Bets on Nigeria Broadband to Chase Down MTN” (May 2017). Bloomberg News. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-05- 25/bharti-airtel-bets-on-nigeria-broadband-to-narrow-gap-with-mtn

99 The Economist. “Business in India: Now for the hard part” (June 2006). Retrieved from http://www.economist.com/node/6969740

100 Norbom, Jon. “International Trade Statistics: 1900-1960” (May 1962). United Nations Statistical Office. Retrieved from https://unstats.un.org/unsd/trade/imts/Historical%20data%201900-1960.pdf; World Bank. World Development Indicators (2016), Exports of goods and services (current US$). Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.EXP.GNFS.CD

101 Kannaiyan, Jay. “Colombia, Part 2: Medellin” (May 2010). Jammin Global Adventures. Retrieved from http://jamminglobal.com/2010/06/colombia-part-2b-medellin.html

102 Panagariya, Arvind. “India’s Trade Reform” (March 2004). India Policy Forum, 1. National Council of Applied Economic Research (New Delhi), Brookings Institution. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/2004_panagariya.pdf

103 Goldberg, Pinelopi, Khandelwal, Amit, and Pavcnik, Nina. “Imported inputs and domestic product growth in India” (December 2008). Centre for Economic Policy Research, VoxEU. Retrieved from http://voxeu.org/article/imported-inputs-and-domestic-product-growth-india

104 Byrne, John A. “IBM now employs more workers in India than US” (October 2013). New York Post. Retrieved from http://nypost.com/2013/10/05/ibm-now-employs-more-workers-in-india-than-us/ 105 Munuswamy, Suresh. “ChotuKool: the $69 fridge for rural India” (December 2009). New Atlas. Retrieved from https://newatlas.com/refridgerator-rural-india-chotukool/13680

106 Abraham, Neenu. “GE Healthcare to make India hub for low-cost devices; products will be up to 40% cheaper” (November 2013). The Economic Times. Retrieved from

https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/healthcare/biotech/healthcare/ge-healthcare-to-make india-hub-for-low-cost-devices-products-will-be-up-to-40-cheaper/articleshow/25282416.cms 107 International Monetary Fund. IMF India GDP Current Prices (1980-2022). Retrieved from Bloomberg terminal, IGN$IND Index; World Bank. World Bank India GDP in Current USD (1960- 2016). Retrieved from Bloomberg terminal, WGDPINDI Index

108 Bloomberg L.P. Bloomberg India Market Cap as a Percentage of World Market Cap USD. Retrieved from Bloomberg terminal, WPERINDI Index; The Economist. “The half-finished revolution” (July 2011). Retrieved from http://www.economist.com/node/18986387

109 Reserve Bank of India. Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy (September 2016), Table 243: Select Debt Indicators of the Central and State Governments (As Percentage to GDP). Retrieved from https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/PublicationsView.aspx?id=17376

110 World Bank. World Development Indicators (2017), Gross fixed capital formation, private sector (% of GDP). Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.GDI.FPRV.ZS

111 Including motorbikes (“two-wheelers”). Government of India, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. Motor Vehicles – Statistical Year Book India (2016). Retrieved from http://www.mospi.gov.in/statistical-year-book-india/2016/189

112 World Bank. World Development Indicators (2017), Air transport, passengers carried. Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IS.AIR.PSGR

113 Aiyar, Swaminathan. “25 years of reforms: Nehru built many strong institutions, almost all have eroded” (July 2016). The Economic Times. Retrieved from

http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/policy/25-years-of-reforms-nehru-built-many strong-institutions-almost-all-have-eroded-says-swaminathan-aiyar/articleshow/53310256.cms 114 The World Bank, International Comparison program database (2017). GDP per capita based on purchasing power parity. Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD 115 World Bank measures defined as the proportion of the population living on less than $3.10 or $1.90 per day at 2011 purchasing power parity rates. The World Bank, Development Research Group. Poverty and Equity Database (2016). Retrieved from

http://iresearch.worldbank.org/PovcalNet/povOnDemand.aspx; Government of India, Planning Commission. Report of the Expert Group to Review the Methodology for Measurement of Poverty (2014). Retrieved from http://planningcommission.nic.in/reports/genrep/pov_rep0707.pdf; Datt, Gaurav, Ravallion, Martin, and Murgai, Rinku. “Growth, urbanization, and poverty reduction in India” (February 2016). World Bank Group, Poverty and Equity Global Practice Group, Working Paper 7568. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/571221468197063793/Growth urbanization-and-poverty-reduction-in-India

116 International Monetary Fund. IMF India BOP Current Account Exports Services (2016). Retrieved from Bloomberg terminal, 5341R009 Index; International Monetary Fund. IMF India BOP Current Account Imports Services (2016). Retrieved from Bloomberg terminal, 5341R010 Index 117 International Monetary Fund. India BOP Net Financial Account (2016). Retrieved from Bloomberg terminal, 5343R001 Index

118 International Monetary Fund. India Financial Account Portfolio Investment USD (2016). Retrieved from Bloomberg terminal, B6INFP Index; International Monetary Fund. India Fin Acc Balance Direct Investment USD (2016). Retrieved from Bloomberg terminal, B6INFD Index 119 Dua, Pami and Ranjan, Rajiv. “Exchange Rate Policy and Modelling in India” (February 2010). Reserve Bank of India, Department of Economic Analysis and Policy, Development Research Group. Retrieved from https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/PublicationsView.aspx?id=12252 120 Bijoy, C. R. “India: Transiting to a Global Donor” (April 2009). Reality of Aid, Special Report on South-South Cooperation 2010. Retrieved from http://www.realityofaid.org/wp

content/uploads/2013/02/ROA-SSDC-Special-Report6.pdf

121 Aiyar, Swaminathan. “Twenty-Five Years of Indian Economic Reform” (October 2016). The Cato Institute, Policy Analysis No. 803. Retrieved from https://www.cato.org/publications/policy analysis/twenty-five-years-indian-economic-reform

122 Boughton, James M. Tearing Down Walls: The International Monetary Fund, 1990-1999 (February 2012), Chapter 9: Five Fat Years: Recovery from the Debt Crisis, 1990-94. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/history/2012/pdf/c9.pdf 123 Doshi, Vidhi. “How the East India Company became a weapon to challenge UK’s colonial past” (May 2017). The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/may/06/east india-company-british-businessman

124 Rajghatta, Chidanand and Sinhal, Prabhakar. “Full circle: India buys 200 tons gold from IMF” (November 2009). The Times of India. Retrieved from

http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/Full-circle-India-buys-200-tons-gold-from IMF/articleshow/5194338.cms; Prasad, Adjit. “Reserve Bank of India – Bulletin Weekly Statistical Supplement – Extract” (October 2017). Reserve Bank of India, Press Release No. 2017-2018/1087. Retrieved from https://rbi.org.in/Scripts/BS_PressReleaseDisplay.aspx

125 Panagariya, Arvind. India: The Emerging Giant (April 2010), Chapter 5: Phase IV (1988-2006): Triumph of Liberalization. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from

https://books.google.com/books?id=v78VDAAAQBAJ

126 The Economist. “The half-finished revolution” (July 2011). Retrieved from

http://www.economist.com/node/18986387

Legal information and disclosures

The views expressed are the views of the author as of the date indicated on each posting; such views are subject to change without notice. Farley Capital L.P. (Farley Capital)has no duty or obligation to update the information contained herein. Further, Farley Capital makes no representation, and it should not be assumed, that past investment performance is an indication of future results. Any discussion regarding investment returns or financial projections are provided as illustrative examples only and no inference shall be made therefrom regarding the potential for returns on any investment discussed. Moreover, you should be aware that all types of investments involve a significant degree of risk, and wherever there is potential for profit, there is also the possibility of loss.

This content is being made available for informational and educational purposes only and should not be used for any other purpose. The information contained herein does not constitute and should not be construed as financial, legal, or tax advice, or as an offering of advisory services. The information contained herein shall not constitute an offer to sell, or a solicitation to subscribe for, interests in any investment vehicle managed by Farley Capital, which offer or solicitation will only be made to qualified investors and accompanied by a private placement memorandum, subscription agreement, and other related offering documents. Certain information contained herein concerning economic trends and performance is based on or derived from information provided by independent third-party sources. Farley Capital believes that the sources from which such information has been obtained are reliable; however, it cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of such information and has not independently verified the accuracy or completeness of such information or the assumptions on which such information is based.

This content, including the information contained herein, may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted in whole or in part, in any form without the prior written consent of Farley Capital.