Click here to access this dispatch as a formatted PDF.

Part one of a two-part series on the roots and impact of India’s 1991 crisis, this report explores: the historical context that informed the country’s post independence economic system (see below); the details of the interventionist strategy implemented by Nehru, India’s first prime minister (see page 5); the decision to double down on those policies in the 1960s and 70s (see page 10); and the timid reforms of the 1980s, which failed to address India’s increasingly precarious trade and financial imbalances (see page 13). Finally, an appendix to this report provides a primer on balance of payments terminology (see page 20).

Part two of this series (“India since 1991: tiger uncaged”) examines: the immediate lead-up to the 1991 crisis; the chronology of the crisis itself; the subsequent reforms to India’s economic policy; and the economic revitalization stimulated by those reforms. An upcoming series of dispatches will address the impact on India’s macroeconomic stability of its revamped approach to trade and financial policy, as well as the ways in which the liberalization unleashed in 1991 remains a work in progress.

Historical background: from Company Raj to British Raj

Founded in 1600 under a charter granted by Elizabeth I, the East India Company (EIC) was one of the globe’s first multinational corporations.4 In its original incarnation as a commercial enterprise, the EIC generated enormous profits exporting Indian-made goods to Europe. Between 1650 and 1700, shipments of cotton textiles from India to Britain more than quadrupled. After British textile mills lobbied for mercantilist barriers, Parliament banned imports of Indian-made textiles, with an exception for re-exports to continental Europe (all of which were required to be shipped via Britain).5 Indian textile exports continued to grow through the 1700s, driven by shipments to the continental market, where British textile producers – even after implementing major improvements in spinning technology – still could not overcome India’s comparative advantage.6

The EIC functioned as a “franchise of independent entrepreneurs”, tolerating brazen profiteering by its representatives in exchange for their role in securing and expanding its domain. Two of its officials, Robert Clive and his son Edward, amassed the world’s largest single collection of antiquities from the Mughal Empire (which ruled India for over three centuries) during their service with the EIC. The Clives filled their Welsh country estate with “loot from India, room after room of imperial plunder”, assembling a treasure trove that remains in private hands to this day (though much of it is on loan to museums).7

By the mid-1700s, however, the EIC had “ceased to become a conventional corporation”. As it accumulated territory and power, it gradually morphed from a trading operation into the so-called Company Raj: a de facto colonial government that collected taxes, issued coins, and fielded a private army. After running into financial trouble in the 1770s (even as its employees returned to Britain with enormous fortunes), the EIC was saved from bankruptcy by a loan from Parliament. In exchange for this rescue – history’s first example of a “too big to fail” bailout – the British government subjected the EIC to ever-tightening oversight and regulation. This culminated in the 1858 Government of India Act, which formally nationalized the EIC and marked the start of the British Raj.4

By the early 1800s, the British government had effective control over the EIC. In response to continued pressure from its domestic textile industry – which was eager to expand beyond its protected home market – Britain imposed a one-sided form of free trade on India. Parliament hiked the import duty on Indian cotton textiles (including re-exports to continental Europe) to 85%. Meanwhile, the British colonial authorities imposed steep taxes on Indian-made textile products sold in their own home market, while subjecting imported British textiles to minimal tariffs.9 Finally, the pound sterling was deliberately under-valued relative to the Indian rupee – further boosting British exporters at the expense of Indian industry.10

Whereas the Indian market was “thrown wide open” to British manufacturers, heavy tariffs and taxes on Indian textiles and other finished goods relegated the colony to merely supplying raw materials.11 Between 1801 and 1831, the volume of Indian textiles exported to Britain plunged by more than 70%, while the quantity of textiles imported by India from Britain increased more than fivefold.12 Meanwhile, the corrupt practices of the EIC era remained entrenched under the British Raj, whose customs officers were so underpaid “that it was possible for them to live only by extortion”.13

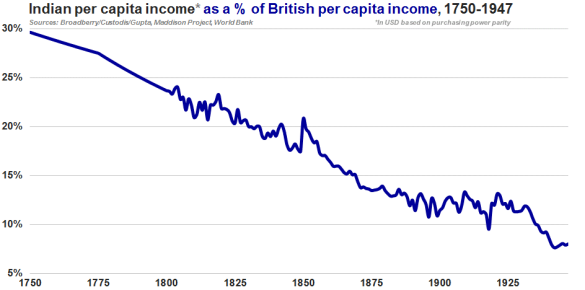

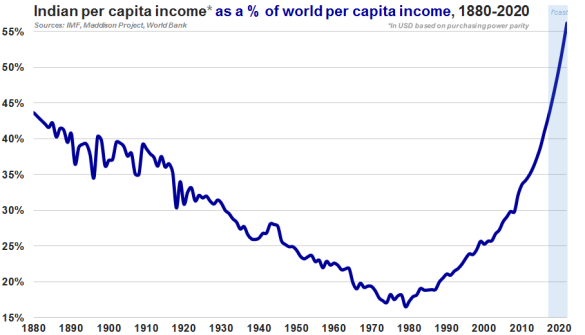

The result was burgeoning prosperity for Britain at the cost of a steady impoverishment of India’s economy. At the inception of the Company Raj in the 1750s, the income of the average Indian was equivalent to 29% of British per capita income. By the time India gained its independence in 1947, its average income had plummeted to just 8% of the British level.14

For the leaders of India’s independence movement – including an increasingly prominent democratic socialist named Jawaharlal Nehru – the lessons of the colonial era were clear. Political independence would be meaningless unless it was combined with “economic independence.”15 To avoid “neo-colonial” exploitation of India’s people and resources16 by modern versions of the East India Company – “whose merchants had become rulers” – India would have to industrialize without relying on imports, foreign investment, or the easily corruptible private sector.17

Rooted in India’s leading pro-independence organization, the Indian National Congress (widely known as Congress) emerged as its dominant political party after 1947 – controlling India’s central government for 54 of its 70 years since independence. Congress has historically been led by a member of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty, named after Jawaharlal Nehru (India’s first prime minister), in office 1947-64, and his daughter Indira Gandhi (no relation to the family of Mahatma Gandhi), prime minister 1966-77 and 1980-84.18

Though not a communist, Nehru was a disciple of the Soviet approach to economic development. In 1927, he visited Moscow and left “profoundly impressed by what he saw and heard.”20 He came to view competition as wasteful, once reportedly asking, “Why do we need nineteen brands of toothpaste?” In a letter to his daughter, Indira, Nehru wrote that, without central planning, competition between private enterprises would inevitably lead to “squandered resources.” 21 When India won its independence in 1947, Nehru – who by then had emerged as Mahatma Gandhi’s designated political heir – became the country’s first prime minister.22

Nehru was the architect of the Non-Aligned Movement of nations advocating a “middle course” between the Cold War’s capitalist and communist blocs. He attempted to maintain friendly relationships with both sides, paying multiple visits to the United States as well as to the Soviet Union during his terms in office.23 Nevertheless, Nehru disparaged developing economies that chose to pursue market-driven development, calling them “Coca-Cola countries.”24

Drawing on his deep distrust of free enterprise and lessons learned from India’s experience at the hands of the British, Nehru sought out an economic blueprint that could make India “self-sufficient” while reducing its dependence on foreign capital and limiting its reliance on the private sector.26 The U.S.S.R. – where, in the decade following World War II, industrial output was growing three times faster than in the U.S.27 – offered what appeared to be an appealing model for the centrally-planned industrialization of a large, agricultural country facing poverty and illiteracy.28

With the help of Soviet aid and advisors, Nehru implemented a highly interventionist, state-led development strategy consisting of substantial public ownership of industrial firms, five-year plans drawn up by a central Planning Commission, an array of controls and restrictions intended to curb imports, and a convoluted set of licenses and permits designed to curtail the private sector.29 Nehru’s administration established state-owned enterprises that monopolized electricity generation, petrochemicals, and telecoms, along with non-industrial businesses ranging from television broadcasting to hotels.30

In industries not reserved for the public sector, even the simplest business decisions were subject the whims of what came to be known as the License Raj – a high-handed bureaucracy that took over where the British Raj had left off.31 Companies had to obtain a “mind-boggling array of permits and licenses” before they could add capacity, hire or fire workers, diversify into new product lines, adjust product pricing or volumes, license foreign technology, or shut down a loss-making plant.32

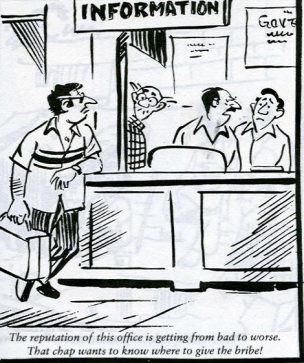

The License Raj stifled competition, deterred entrepreneurship, and incentivized corruption.33 Because it set a higher bar for applications to expand than for requests to build new plants, the system prevented successful firms from taking advantage of economies of scale.34 Established producers learned to game the bureaucracy, hoarding licenses not only to accommodate their own production, but also to shut out potential competitors.35 Unsurprisingly, the licensing regime became “a major source of leverage to extract funds from India’s business community”, with those “generous to the ruling Congress Party […] ‘allowed to amass huge fortunes’ and those who were ungenerous […] ‘faced with excruciating delays, tax raids, and government harassment’”.36

Meanwhile, controls and restrictions on foreign trade – aimed at promoting “self reliance” – were designed to make life all but impossible for would-be importers. Before the government would even consider an import request, a business had to apply for and obtain a “non-availability certificate” – proof that no Indian supplier could provide the product in question. The bizarre implementation of regulations barring imports of goods by anyone other than their “actual user” meant that bus and trucking companies could not import tires for their vehicles, and were instead forced to procure them from vehicle manufacturers.38

Certain commodities, including oil, steel, rubber, and newsprint, could only be brought into the country via monopoly government trading organizations. Imports of most consumer goods were effectively banned. Finally, “to be on the safe side,” the system subjected foreign-made goods that did manage to slip through the cracks to some of the highest tariffs in the world.34 These policies did succeed in restraining imports, enabling Nehru to manage India’s balance of payments, conserve foreign exchange, and avoid a politically-damaging devaluation of the rupee – which remained pegged at 13.33 per pound sterling for nearly two decades (until 1966, when it was finally devalued and re-pegged to the U.S. dollar – see next section).39

The unintended consequences of India’s protectionism, however, meant that the country’s “anti-import system [was] also an anti-export system.”34 Keeping the currency artificially over-valued limited exporters’ competitiveness in foreign markets (Nehru appeared not to be fazed by the irony that one of Mahatma Gandhi’s key demands of the British Raj had been an end to its overvaluation of India’s currency). Strict import controls prevented prospective Indian exporters from acquiring crucial capital equipment and production inputs that lacked domestically-produced substitutes. In the early 1980s, it took one entrepreneur – Narayana Murthy, the co-founder of Infosys – three years and fifty trips to Delhi to obtain a license to import a computer.40

Given the lucrative opportunities available to well-connected cronies in India’s domestic market, many businesspeople determined that exports were simply not worth their while. The combination of import barriers, licensing, and entrenched corruption allowed the politically-savvy to establish monopolies and cartels that faced little incentive to innovate or improve productivity. Sheltered from competition and cut off from foreign technology, they were able to generate steady profits selling Indians low-quality, antiquated goods.41

In the automobile industry, limits on competition and capacity, combined with price controls, allowed just two manufacturers – Hindustan Motors and Premier Automobiles – to establish a duopolistic “sellers’ market”, featuring multi-year waiting lists for cars whose designs and features remained virtually unchanged for decades.42 As a result, used automobiles (which were not subject to price controls) cost more than new ones in pre-1991 India – illustrating the economic distortion wrought by the License Raj.43

Envisioned as a means of protecting India from exploitation by industrialists and foreigners, Nehru’s policies had the effect of limiting the opportunities available to India’s poor while sheltering a handful of crony capitalists from both domestic and foreign competition. In the end, his well-intentioned but misguided economic strategy benefited “only [the] bureaucrats, politicians, and a small elite of protected businessmen [who] flourished from the management of scarcity.”32

By the early 1960s, India’s industrial production and exports were stagnant. Two brief wars (with China in 1962 and Pakistan in 1965) prompted a doubling of the defense budget, contributing to a deteriorating fiscal situation.46 Meanwhile, consecutive droughts in 1965-66 led to increasing inflation and a depletion of India’s foreign exchange reserves. In 1966, Indira Gandhi (daughter of Nehru, who had died in office in 1964) was elected prime minister. In an effort to head off a balance of payments crisis, Mrs. Gandhi immediately sought assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank.47

The two Washington, D.C.-based institutions recommended a devaluation of the rupee and promised billions of dollars in aid in exchange for broad-based economic reforms. Though India devalued its currency by a massive 57% (from 13.33 per pound sterling, or 4.76 per U.S. dollar, to a new peg of 7.50 per U.S. dollar),48 most of that pledged assistance did not materialize – officially, due to the inadequacy of the Indian government’s liberalization package. In reality, the bailout was vetoed by the administration of Lyndon B. Johnson, in an expression of its irritation with India’s vocal opposition to the Vietnam War.49

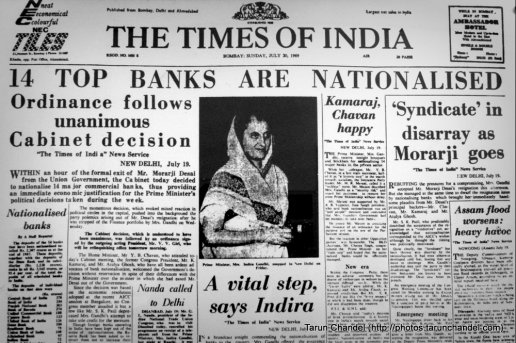

The result was a political disaster for Indira Gandhi, who had taken a major political gamble by devaluing the rupee but failed to secure anything in return. She promptly aborted the reform program and re-cast herself as a radical populist, under the slogan garibi hatao (“abolish poverty”). “A decade of economic vandalism followed”,50 as her administration took a hard leftward turn, nationalizing most of the country’s banks, insurers, steel mills, and oil

companies.51 In 1969, Mrs. Gandhi’s government enacted the Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Act (MRTP), which declared all private companies with assets above 200 million rupees ($27 million at the then-prevailing exchange rate) “monopolies” and effectively barred them from expanding.82

The 1973 Foreign Exchange Regulation Act (FERA) strictly limited dealings in foreign currency, further stifling Indians’ ability to conduct business internationally. Movie theaters, which could no longer obtain the dollars necessary to show recent Hollywood hits, resorted to running ancient Charlie Chaplin films.53 FERA also imposed a 40% ceiling on foreign ownership of companies incorporated in India. Coca-Cola, IBM, Mobil, and Kodak chose to close down their Indian subsidiaries rather than give up control of their local operations.54 India endured a constitutional crisis and an extraordinarily controversial 21-month suspension of democracy before Indira Gandhi was finally ousted from power in 1977.

As the 1970s drew to a close, the shortcomings of the Nehru-Gandhi state-driven development model were becoming increasingly indisputable. In 1945, the income of the average Indian was equivalent to roughly 28% of the global average. By 1979 – the year before Indira Gandhi returned for her third term as prime minister – that ratio had plunged to a trough of just 17% of the world average.55 Establishment economists coined the belittling term “Hindu rate of growth”, implicitly attributing India’s lackluster economic performance to the nation’s cultural and religious traditions. Of course, India’s post-1991 economic record makes clear that the issue was never a lack of talent, skill, or entrepreneurial dynamism.56

Indira Gandhi was re-elected in January 1980, following an opposition party’s move to imprison her that backfired and generated a wave of public sympathy.57 By then, it “must have been clear to [her]” that the economic policies of her previous terms in office had stunted India’s economy and failed to deliver on the promise of her anti-poverty platform. Politically, Mrs. Gandhi and her advisors calculated that a less-hostile relationship with the private sector offered the best potential for boosting growth and, by extension, for improving voters’ livelihoods.58 Building on a cautious liberalization of import rules that had begun in the late 1970s, her administration continued a policy of easing the state’s grip on the economy.59

After the 1973 collapse of the Bretton Woods system of fixed currency pegs, nations gained the flexibility to introduce more market-driven exchange rate arrangements. Nevertheless, India chose to simply replace the rupee’s single currency peg (which had alternated between the U.S. dollar and pound sterling) with a multi-currency peg – linking the currency to a weighted basket comprising the dollar, yen, pound sterling, and deutsche mark. Under this “basket peg”, as late as 1981, one U.S. dollar bought just 7.81 rupees – barely more than the exchange rate of 7.50 per dollar established in 1966,60 when Mrs. Gandhi had been forced to devalue the rupee, in “an act still regarded by Indian politicians as a national humiliation.”61

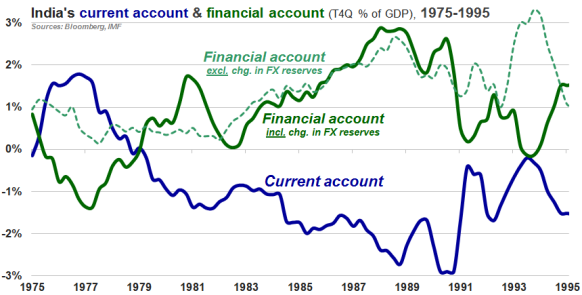

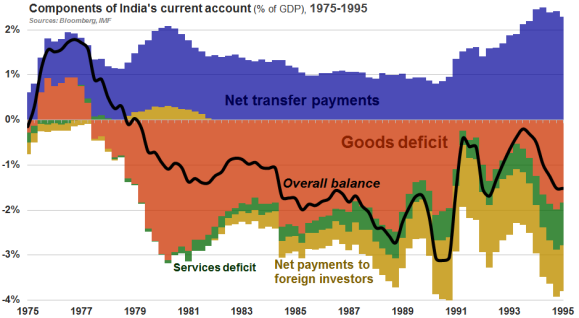

In the early 1980s, following a severe drought and the more-than-doubling of oil prices in the wake of the 1979 Iranian revolution, India’s current account swung from a modest surplus to a sizeable deficit. During this period, partial deregulation contributed to a mini-boom in exports. However, the competitveness of Indian exporters remained constrained by the government’s reluctance – despite relatively high domestic inflation – to allow the over-valued rupee to depreciate. As a result, imports grew at an even faster pace.62

Seeking to pre-empt a possible balance of payments crisis, Indira Gandhi’s new administration began negotiating with the International Monetary Fund for India’s second IMF bailout. In contrast to 1966, in 1981 India was able to obtain billions of dollars in “low-conditionality” loans from the IMF, which at the time was “under pressure from both borrowers and creditors to play a more active role in helping the oil-importing developing countries cope” with the oil shocks of the prior decade.63

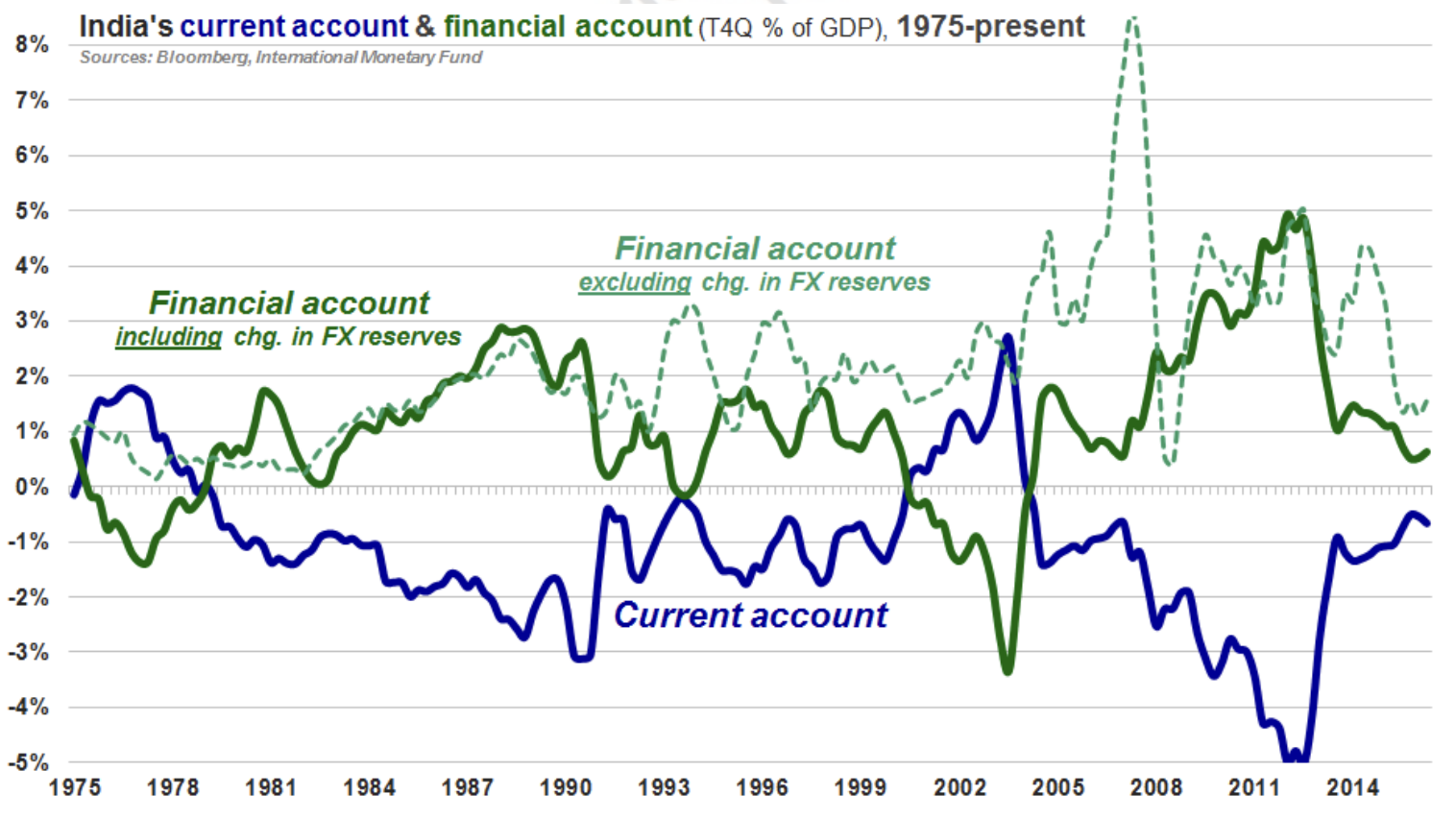

A current account deficit is principally a trade deficit, which implies a net flow of capital out of a country. A financial account surplus is the capital that must flow into a country to offset that trade deficit. For a detailed primer on , please refer to the appendix.

Although the 1981 IMF loans came with virtually no strings attached, the 1980s proved to be a turning point,64 as Indira Gandhi and her son Rajiv Gandhi (who took office following her assassination in 1984) pursued incremental reforms. Their administrations relaxed the rules that had constrained large companies’ ability to expand, allowed Indian automakers to form joint ventures with foreign partners, and introduced limited tax incentives for private-sector investment.65

A “low-key”, soft-spoken airline pilot married to an Italian-born model, Rajiv Gandhi (prime minister 1984-89) entered politics reluctantly. He was thrust into the spotlight in 1980, after his younger brother Sanjay – whom Indira Gandhi had been grooming as her successor – died in a plane crash just five months after winning a seat in parliament. Rajiv took over as prime minister in 1984, when his mother was assassinated by her bodyguards.66

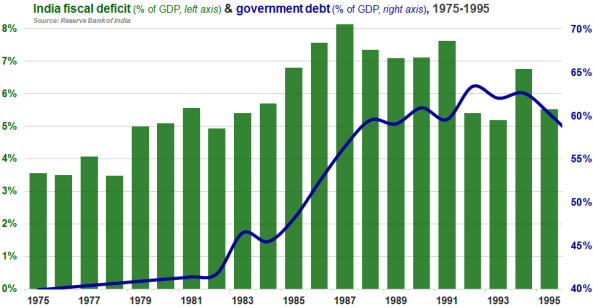

Rajiv Gandhi, in particular, “seemed to bring a new attitude”, declaring that “[a] poor country cannot afford to carry on billing the poorest people for its inefficiency and call itself socialist.”34 Blaming the economy’s unsatisfactory growth on a combination of overly conservative fiscal policy and excessive red tape, Mr. Gandhi ran up budget deficits and attempted to implement structural reforms. His government cut taxes, hiked public sector wages, introduced large-scale subsidies for exporters, boosted expenditures on foreign-made defense equipment, and further eased import restrictions.67

The Congress party waved through Rajiv Gandhi’s spending spree, while diluting or blocking his bolder policies – including proposed overhauls of the License Raj, tax code, and capital markets regulation. Mr. Gandhi’s more ambitious ideas faced opposition not only from within his own party, but also from vested interests, including India’s industrialists – who had mastered the art of “briefcase politics” (i.e., bribing bureaucrats in order to secure licenses and shut out would-be competitors)68 – as well as public-sector employees. For example, though Mr. Gandhi was a vocal critic of India’s government-run firms – three quarters of which were losing money by the end of his term82 – his administration was unable to privatize or even shut down a single state-owned company.32

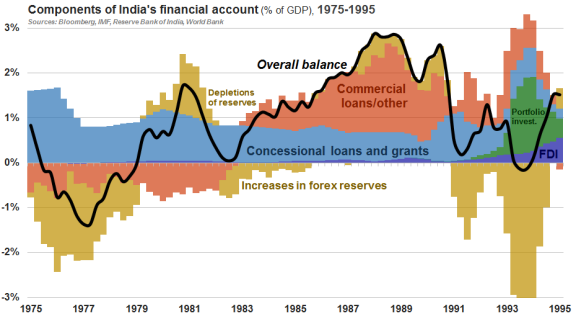

Looser import controls contributed to surging purchases of foreign machinery and technology.58 In the first half of the 1980s, however, the resulting pressure on India’s current account was mitigated by robust domestic petroleum production. Crucially, during this period India was able to fund much of its current account deficit via subsidized borrowings (i.e., so-called “concessional” loans from the IMF and others) as well as direct foreign aid, with limited reliance on commercial financing.69

The state of India’s balance of payments grew more precarious in the second half of the 1980s, as Rajiv Gandhi’s administration attempted to “spend [its] way out of” multiple political setbacks70 – most notably, a 1987 scandal implicating several Indian politicians, including the prime minister himself, in kickbacks paid in connection with a major artillery contract awarded to Bofors, a Swedish arms manufacturer.71 Ignoring increasingly frantic warnings from the central bank and finance ministry, Mr. Gandhi allowed the government’s deficits to balloon to such an extent that India became more and more dependent on foreign loans.

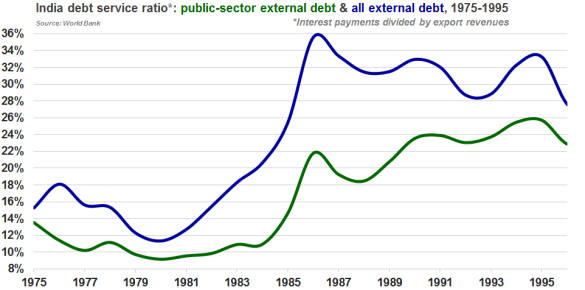

At first, mounting fiscal deficits were financed by a heavy-handed crowding out of domestic private-sector borrowing (specifically, by requiring banks to invest a higher share of deposits in government bonds).72 Eventually, however, the government was forced to rely on external sources of financing. With subsidized forms of credit largely tapped out, this meant borrowing on commercial terms. International lenders – apparently having learned nothing in the aftermath of the Latin American debt crisis – were happy to oblige.49 From the mid-1980s to 1990, the portion of India’s current account deficit that was funded by commercial, non concessional loans jumped from 24% to 80%.73

“It was already clear by 1986 that we were in an internal debt trap which would soon engulf us in an external debt trap. Rather than take any remedial action, we went merrily along, borrowing more and more at home and on shorter and shorter terms abroad.”74

I.G. Patel, former Governor of the Reserve Bank of India

Unsurprisingly, an economic strategy reliant on debt-fueled public spending failed to narrow India’s trade deficit. Exports, while growing, were unable to keep pace with the country’s rising import bill.49 The result – escalating current account deficits – had to be offset with ever-greater financial account surpluses, even as mounting fiscal deficits meant an increasing share of capital inflows had to be diverted into financing government debt. Between 1985 and 1991, India’s external borrowings jumped 118%, to $85 billion; the public-sector portion of that debt ballooned 156%, to $73 billion.75 By the late 1980s, interest payments on India’s external borrowings consumed over a third of the country’s export revenues.76

An alternate way of defining a current account deficit is as the difference between a country’s savings and its investment. Put another way, a financial account surplus represents the amount of capital a country running a current account deficit must attract from the rest of the world to meet the gap between its domestic savings (public and private) and its domestic investment.77

Economic theory suggests that when a country’s current account deficit expands as a result of higher domestic growth, that growth attracts the kind of incremental foreign investment (e.g., expansions of overseas manufacturers’ domestic production facilities) that increases the country’s productive capacity, “enabling [it] to pay off any debts incurred.”78 By contrast, when a country’s current account deficit expands as a result of fiscal profligacy (that is, declining domestic savings), it is less likely to attract the type of foreign investment that would increase the country’s ability to repay its external liabilities down the line.79

Before 1991, India had “the dubious distinction of being the most controlled economy in the non-Communist world.”80 According to Suresh Krishna, chairman of a Chennai-based industrial conglomerate, “[t]o call it a controlled economy is an understatement. It was a very suffocating kind of economic system.” In 1981, Krishna recounts, officials in Delhi refused to allow him to double his plant’s capacity until he agreed to sell half of his business to the public – at a valuation set by government bureaucrats.81 Around the same time, managers at Procter & Gamble India spent months living in fear of prosecution, after the company responded to a flu epidemic by producing cough suppressant in excess of its government-authorized capacity.82

Indira and Rajiv Gandhi “picked the lowest of low-hanging fruit” during the 1980s.83 While their relatively modest policy changes helped resuscitate India’s economy, they failed to lower barriers to competition and trade, and were insufficient to sustain a decent rate of growth.84 As early as 1988, the IMF “knew that India was heading for trouble” and reached out to Rajiv Gandhi’s government to propose a “stand-by arrangement” – the Fund’s term for an agreement providing financial aid in exchange for stipulated structural reforms. Mr. Gandhi turned down the plan, which he feared would compound his already-numerous political liabilities in the approaching general election.70

By the end of the 1980s, India was lurching toward the edge of a financial precipice.85 At the same time, the country’s politics began to descend into escalating turmoil, and the window of opportunity that Rajiv Gandhi had been granted to liberalize policy seemed “unlikely to be repeated.” Nevertheless, the conclusion of The Economist’s May 1991 “tiger caged” report – which predicted that “[t]he tiger will not be freed for some yet” – was about to proven dramatically wrong.2 Part two of this series tells the story of the calamitous crisis – amplified by assassinations, covert airlifts of gold bars, and the collapse of the Soviet Union – that finally unshackled India’s economy and unleashed a tidal wave of change.

* * *

Andrei Stetsenko

August 18, 2017

Appendix: balance of payments terminology

Each country’s balance of payments represents all monetary transactions between its citizens, businesses, and government and the rest of the world. The two key components of a country’s balance of payments are its current account and financial account.86

The current account measures international transactions that represent income for the recipient. It comprises a country’s trade balance (exports less imports) in goods and services, plus the net flow of factor income (such as dividends from abroad, or interest paid to foreign creditors) and transfer payments (such as remittances sent from abroad, or foreign tourists’ expenditures in the country).

The flip-side of the current account is the financial account, which records international exchanges of assets and liabilities. It measures the net flow of foreign direct investment (FDI), portfolio investment (comprising both equities and bonds), and other forms of investment (including loans and acquisitions of domestic currency). The financial account also includes changes in foreign currency reserves.

It is an accounting identity that the components of any country’s balance of payments must sum to zero. When a resident of Mumbai buys a ₹5,000 ($78) Microsoft software application, for example, the transaction gets recorded twice: once as a -₹5,000 debit under imports (part of the current account), and once as a +₹5,000 credit to the financial account, as Microsoft has increased its holdings of Indian currency.

A country, such as India, that runs a current account deficit must offset it by importing capital – that is, by running an equivalent financial account surplus. This build-up of liabilities to the rest of the world is associated with future obligations, such as dividends disbursed to foreign holders of domestic stocks (which flow through the current account) and repayments of funds borrowed from foreign lenders (which flow through the financial account).

The mechanism by which mismatches between an economy’s current account and its financial account are corrected varies depending on its currency’s exchange rate system (see below).

Free-floating currencies (e.g., U.S., Eurozone):

• If the net flow of capital into an economy with a free-floating currency exceeds its current account deficit, its currency will appreciate (and/or its domestic prices will inflate).

• Conversely, if not enough capital is available or willing to flow in to cover the economy’s current account deficit, its currency will depreciate (and/or its domestic prices will deflate) until its current account deficit narrows and equilibrium is restored.

Fixed currency exchange rates (e.g., Hong Kong, 1991 India):

• If the net flow of capital into an economy whose currency’s value is fixed (a.k.a. “pegged”) to another currency (or basket of other currencies) exceeds its current account deficit, the same mechanism applies as for economies with managed floating currencies (see next page).

• If not enough capital is available or willing to flow in to cover the economy’s current account deficit, the central bank must make up the shortfall by drawing down its foreign-currency reserves.

o If reserves are insufficient, the central bank’s only options are to restrict outflows (by imposing capital controls) and/or devalue the currency.

Managed floating currencies (e.g., Singapore, present-day India):

• If the net flow of capital into an economy whose currency is neither fixed nor completely free-floating exceeds its current account deficit, the central bank can curb the extent of the resulting currency appreciation by printing more of its currency, selling that newly-created currency, and using the resulting proceeds to accumulate foreign currency.

o The central bank’s ability to do so is limited only by its willingness to create more of its currency, which may be subject to political constraints (see Swiss National Bank, 2015).

o The RBI and other central banks employing this means of curbing currency appreciation generally “sterilize” the resulting expansion in the money supply (and its potentially inflationary effect) by selling bonds to soak up the new cash.

• If not enough capital is available or willing to flow in to cover the economy’s current account deficit, the central bank can curb the extent of the resulting currency depreciation by drawing down its foreign-currency reserves.

o Its ability to do is limited by the amount of its accumulated reserves; if reserves are insufficient, the central bank must allow the currency to depreciate until equilibrium is restored.

Under the managed float system it employs today, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) allows the rupee to fluctuate in response to market forces – including permitting the currency to depreciate to help contain current account deficits. In contrast to the hands-off approach of central banks overseeing completely free-floating currencies, however, the RBI continues to intervene in the foreign exchange market. Crucially, the RBI has focused its intervention on averting excessive rupee appreciation, by purchasing foreign currency whenever the net inflow of capital into India (i.e., the country’s financial account surplus) exceeds the amount necessary to fund India’s current account deficit.87

Legal Information and Disclosures

The views expressed are the views of the author as of the date indicated on each posting; such views are subject to change without notice. Farley Capital L.P. (Farley Capital) has no duty or obligation to update the information contained herein. Further, Farley Capital makes no representation, and it should not be assumed, that past investment performance is an indication of future results. Any discussion regarding investment returns or financial projections are provided as illustrative examples only and no inference shall be made therefrom regarding the potential for returns on any investment discussed. Moreover, you should be aware that all types of investments involve a significant degree of risk, and wherever there is potential for profit, there is also the possibility of loss.

This content is being made available for informational and educational purposes only and should not be used for any other purpose. The information contained herein does not constitute and should not be construed as financial, legal, or tax advice, or as an offering of advisory services. The information contained herein shall not constitute an offer to sell, or a solicitation to subscribe for, interests in any investment vehicle managed by Farley Capital, which offer or solicitation will only be made to qualified investors and accompanied by a private placement memorandum, subscription agreement, and other related offering documents. Certain information contained herein concerning economic trends and performance is based on or derived from information provided by independent third-party sources. Farley Capital believes that the sources from which such information has been obtained are reliable; however, it cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of such information and has not independently verified the accuracy or completeness of such information or the assumptions on which such information is based.

This content, including the information contained herein, may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted in whole or in part, in any form without the prior written consent of Farley Capital.

References and Notes

1 The Economist. “India’s brave budget” (March 1992). 322:7749, page 16. Retrieved from https://www.nypl.org/collections/articles-databases/economist-historical-archive-1843-2008 2 Crook, Clive. “A Survey of India: Small world” (May 1991). The Economist, 319:7705, pages 139- 142. Retrieved from https://www.nypl.org/collections/articles-databases/economist-historical archive-1843-2008

3 Crook, Clive. “A Survey of India: Caged” (May 1991). The Economist, 319:7705, page 137. Retrieved from https://www.nypl.org/collections/articles-databases/economist-historical-archive 1843-2008

4 The Economist. “The Company that ruled the waves” (December 2011). Retrieved from http://www.economist.com/node/21541753

5 Clingan, Edmund. Capitalism: A Modern Economic History (July 2015), Chapter 6: National Economic Planning and Finance. iUniverse. Retrieved from

https://books.google.com/books?id=6VNJCgAAQBAJ

6 Faust, David R. and Porter, Philip W. A World of Difference: Encountering and Contesting Development (August 2009), Chapter 15: The End of Colonialism and the Promise of Free Trade. Guilford Press. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=1jnW5kh55EMC 7 Dalrymple, William. “The East India Company: The original corporate raiders” (March 2015). The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/04/east-india-company original-corporate-raiders

8 West, Benjamin. “Shah 'Alam, Mughal Emperor (1759–1806), Conveying the Grant of the Diwani to Lord Clive, August 1765” (c. 1818). British Library. Retrieved from

https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/shah-alam-mughal-emperor-17591806-conveying-the-grant-of the-diwani-to-lord-clive-august-1765-191206

9 Li, Menggang. Research on Industrial Security Theory (December 2013). Springer Science & Business Media. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=bni8BAAAQBAJ 10 Bhavnani, Rikhil R. and Jha, Saumitra. “Trade Shocks and pro-Democracy Mass Movements: Evidence from India’s Independence Struggle” (January 2013). University of Wisconsin-Madison, Department of Political Science and Stanford University, Graduate School of Business. Retrieved from https://bcep.haas.berkeley.edu/conferences/docs/Jha.pdf

11 Meena, H. K. “British Industrial Policy and Decline of Handicrafts in 19th & 20th Century” (April 2016). International Journal of Advances in Social Science and Humanities, 4:4. Retrieved from http://www.ijassh.com/download2.php?f=0504042016IJASSH.pdf

12 Broadberry, S., Custodis, J., and Gupta, B., “India and the great divergence: an Anglo-Indian comparison of GDP per capita, 1600-1871” (November 2015). Explorations in Economic History, 55, pages 58-75. Retrieved from http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/56838

13 Dutt, Romesh C. The Economic History of India Under Early British Rule (1950), Chapter 17: Internal Trade, Canals, and Railroads. Routledge. Retrieved from

https://books.google.com/books?id=LVptQixEDj4C

14 The World Bank, International Comparison program database. GDP per capita based on purchasing power parity (2017). Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/

NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD; Bolt, J. and J. L. van Zanden, “The Maddison Project: collaborative research on historical national accounts”. The Economist History Review (2014); 67(3): 627-651. Retrieved from http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison-project/data.htm; Broadberry, S., Custodis, J., and Gupta, B., “India and the great divergence: an Anglo-Indian comparison of GDP per capita, 1600- 1871” (November 2015). Explorations in Economic History, 55, pages 58-75. Retrieved from http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/56838

15 Roffelsen, Cees. “How Nehru Shaped India’s Development” (September 2016). Medium. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@ceesroffelsen/how-nehru-shaped-indias-development 4df38535bf98

16 Sinha, Yashwant. “25 years of reforms: Directions of reforms must shift towards fulfilling people’s felt needs” (July 2016). The Economic Times. Retrieved from

http://blogs.economictimes.indiatimes.com/et-commentary/25-years-of-reforms-direction-of-reforms must-shift-towards-fulfilling-peoples-felt-needs/

17 Tharoor, Shashi. From Midnight to the Millennium (August 1997). Viking. Excerpt retrieved from http://indiabefore91.in/node/6/submission/21

18 Dhume, Sadanand. “The decline and downfall of India’s Congress party” (May 2016). The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-decline-and-downfall-of-indias congress-party-1463676893

19 Sputnik Images. “Leonid Brezhnev and Jawaharlal Nehru” (August 1961). RIA Novosti. Retrieved from http://visualrian.ru/en/site/gallery/index/id/29790

20 Mohanty, Arun. “Remembering Nehru’s first ever visit to the USSR” (November 2012). Russia & India Report. Retrieved from

https://in.rbth.com/articles/2012/11/29/remembering_nehrus_first_ever_visit_to_the_ussr_19431 21 Das, Gurcharan. India Unbound (April 2002), Chapter 10: Caste and Chapter 7: Capitalism for the Rich, Socialism for the Poor. Anchor Books.

22 Yergin, Daniel and Stanislaw, Joseph. The Commanding Heights (1998). Free Press. Excerpt retrieved from https://www-tc.pbs.org/wgbh/commandingheights/shared/pdf/prof_jawaharlalnehru.pdf 23 Rauch, Carsten. “Farewell Non-Alignment?” (April 2008). Peace Research Institute Frankfurt, Report No. 85. Retrieved from https://www.hsfk.de/fileadmin/HSFK/hsfk_downloads/prif85.pdf 24 Bidwai, Praful. “India and the world: Foreign policy’s shrinking horizons” (September 1999). The Tribune. Retrieved from http://www.tribuneindia.com/1999/99sep27/edit.htm

25 Steel Authority of India Limited. “About Bhilai Steel Plant” (2012). Retrieved from https://sail.co.in/bhilai-steel-plant/about-bhilai-steel-plant

26 Aiyar, Swaminathan. Escape from the Benevolent Zookeepers (December 2007). The Times Group Books. Excerpt retrieved from https://www.cato.org/articles/introduction-0

27 Sabillon, Carlon. Manufacturing, Technology, and Economic Growth (2000), Chapter 6: The USSR-Russia During the 1950 to 1997 Period. M.E. Sharpe. Retrieved from

https://books.google.com/books?id=CZCD4Ik-K-oC

28 Mironov, Leonid. “Nehru’s First Visit to Soviet Union” (November 2008). Mainstream Weekly, 46:47. Retrieved from https://www.mainstreamweekly.net/article1022.html

29 Bhattacharjee, Subhomoy. “Plan panel out, Yojana Bhawan to get new name” (August 2014).Indian Express. Retrieved from http://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-others/plan-panel-out

yojana-bhawan-to-get-new-name/

30 Dubey, Muchkund. “Indo-(Soviet) Russian Relations” (September 2012). Mainstream Weekly, 50:40. Retrieved from https://mainstreamweekly.net/article3704.html

31 Virmanil, Arvind. “The god that failed: Nehru-Indira socialist model placed India in precipitous decline relative to the world” (November 2013). The Times of India. Retrieved from http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/edit-page/The-god-that-failed-Nehru-Indira-socialist-model-placed India-in-precipitous-decline-relative-to-the-world/articleshow/26112532.cms

32 Bhala, Raj. “First Generation Indian External Sector Reforms in Context” (2013). Trade, Law and Development, 5:1. Retrieved from https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/handle/1808/13045 33 Singh, Ajit. “The Past, Present, and Future of Industrial Policy in India: Adapting to the Changing Domestic and International Environment” (December 2008). University of Cambridge, Centre for

Business Research. Retrieved from https://www.cbr.cam.ac.uk/fileadmin/user_upload/centre-for business-research/downloads/working-papers/wp376.pdf

34 Crook, Clive. “A Survey of India: Plain tales of the license raj” (May 1991). The Economist, 319:7705, pages 145-149. Retrieved from https://www.nypl.org/collections/articles

databases/economist-historical-archive-1843-2008

35 Centre for Civil Society. India Before 1991: Stories of Life Under the License Raj (March 2016). Retrieved from https://spontaneousorder.in/india-before-1991-stories-of-life-under-the-license-raj bfd108e6055b

36 Riley, Parkes and Roy, Ravi K. “Corruption and Anticorruption: The Case of India” (2016). Journal of Developing Societies, 32:1, pages 73-99. Retrieved from

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0169796X15609755

37 Laxman, RK. “Best of RK Laxman’s cartoons” (1992). The Times of India. Retrieved from http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/best-of-rk-laxmans-cartoons/photostory/45944726.cms 38 Watkins, Thayer. “The Economic History and the Economy of India” (2007). San Jose State University. Retrieved from http://www.applet-magic.com/india.htm

39 Business Standard. “Let’s get the facts right” (August 2013). Retrieved from http://www.business standard.com/article/opinion/let-s-get-the-facts-right-113081800647_1.html

40 Murthy, N. R. Narayana. “25 years of reforms: When Narayana Murthy took 3 years and 50 trips to Delhi to import one computer” (July 2016). The Economic Times. Retrieved from http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/ites/25-years-of-reforms-when-narayana-murthy-took-3- years-and-50-trips-to-delhi-to-import-one-computer/articleshow/53308935.cms

41 Das, Gurcharan. India Unbound (April 2002), Chapter 7: Capitalism for the Rich, Socialism for the Poor. Anchor Books.

42 Baggonkar, Swaraj. “40 years ago…And now: From 32,000 cars a year to 2.5 million” (January 2015). Business Standard. Retrieved from http://www.business-standard.com/article/pf/40-years ago-and-now-from-32-000-cars-a-year-to-2-5-million-115012500809_1.html

43 Aiyar, Swaminathan. From Narasimha Rao to Narendra Modi: 25 Years of Swaminomics (December 2016). The Times Group Books. Excerpt retrieved from

http://indiabefore91.in/node/6/submission/5

44 “Hindustan Ambassador” (1979). Pinterest, Vintage Car Advertising. Retrieved from https://www.pinterest.com/pin/374643262737727903

45 U.S. Embassy New Delhi. “President and Mrs. John F. Kennedy greet Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Mrs. Gandhi” (November 1961). Retrieved from

https://www.flickr.com/photos/usembassynewdelhi/5387014348/in/album-72157626755988834/ 46 The World Bank, World Development Indicators (2017). Military expenditure (% of GDP). Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS

47 Kirk, Jason A. India and the World Bank: The Politics of Aid and Influence (2011), Chapter 1: The First Half-Century: From Bretton Woods to India’s Liberalization Era. Anthem Press. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=nALKqdykmrwC

48 Shah, Paarth. “Economic Milestone: Devaluation of the Rupee (1966)” (August 2014). Forbes India. Retrieved from http://www.forbesindia.com/article/independence-day-special/economic milestone-devaluation-of-the-rupee-(1966)/38407/1

49 Mital, Ankit. “India and liberalization: There was a 1966 before 1991” (January 2016). Livemint. Retrieved from http://www.livemint.com/Sundayapp/h4nQPwoxX2j8HnftPQt2BI/India-and liberalization-There-was-a-1966-before-1991.html

50 Ibid.

51 Rosser, John B. and Rosser, Marina V. Comparative Economics in a Transforming World Economy (2004), Chapter 16: India: The Elephant Walks. MIT Press. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=y3Mr6TgalqMC

52 Chandel, Tarun. “14 top banks are nationalized” (July 2015). Retrieved from

http://mycbou.blogspot.com/2015/07/14-top-banks-are-nationalised-on-19th.html

53 Aiyar, Swaminathan. From Narasimha Rao to Narendra Modi: 25 Years of Swaminomics (December 2016). The Times Group Books. Excerpt retrieved from

http://indiabefore91.in/node/6/submission/6

54 Panchal, Salil. “Economic Milestone: Exit of the MNCs” (August 2014). Forbes India. Retrieved from http://www.forbesindia.com/article/independence-day-special/economic-milestone-exit-of-the mncs-(1977)/38431/1

55 The World Bank, International Comparison program database. GDP per capita based on purchasing power parity (2017). Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/

NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD; Bolt, J. and J. L. van Zanden, “The Maddison Project: collaborative research on historical national accounts”. The Economist History Review (2014); 67(3): 627-651. Retrieved from http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison-project/data.htm

56 Sanyal, Sanjeev. “25 years of reforms: Why 1991 is a turning point of similar importance as 1947” (July 2016). The Economic Times. Retrieved from http://blogs.economictimes.indiatimes.com/et commentary/25-years-of-reforms-why-1991-is-a-turning-point-of-similar-importance-as-1947/ 57 Satish, D.P. “How jailing Indira Gandhi gave her a new lease of life & sank the Morarji Desai government” (December 2015). News18. Retrieved from http://www.news18.com/news/politics/how jailing-indira-gandhi-gave-her-a-new-lease-of-life-sank-the-morarji-desai-government-1178833.html 58 Kohli, Atul. “Politics of Economic Growth in India, 1980-2005” (April 2006). Economic and Political Weekly, 41:14. Retrieved from http://www.princeton.edu/~kohli/docs/PEGI_PartI.pdf 59 Mital, Ankit. “The long road to the 1991 economic crisis” (July 2016). Livemint. Retrieved from http://www.livemint.com/Sundayapp/E0rCYXfJyjWd2qsENV3KOO/The-long-road-to-the-1991- economic-crisis.html

60 Verghese, S. K. “Exchange Rate of Indian Rupee since Its Basket Link” (July 1979). Economic and Political Weekly, 14:28, pages 1160-1165. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4367782 61 The Economist. “The past is forgotten, maybe” (August 1981). 280:7196, page 54. Retrieved from https://www.nypl.org/collections/articles-databases/economist-historical-archive-1843-2008 62 Chowdhury, Jayanta R. “Lessons from a tale of two rupee devaluations” (June 2013). The Telegraph. Retrieved from http://www.telegraphindia.com/1130624/jsp/business/story_17040688.jsp 63 Boughton, James M. Silent Revolution: The International Monetary Fund, 1979-1989 (October 2001), Chapter 13: Lending for Adjustment and Growth. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/history/2001/ch13.pdf

64 Other factors certainly also contributed to faster growth during this decade, in particular broadening adoption across India of “Green Revolution” agricultural technologies. Fujita, Koichi. “The Green Revolution and Its Significance for Economic Development” (June 2010). JICA Research Institute, Working Paper 17. Retrieved from https://www.jica.go.jp/jica

ri/publication/workingpaper/jrft3q000000231s-att/JICA-RI_WP_No.17_2010.pdf

65 Corbridge, Stuart. “The Political Economy of Development in India Since Independence” (2009). London School of Economics, Development Studies Institute, Handbook of South Asian Politics. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/6610285.pdf

66 Weisman, Steven R. “Assassination in India; Rajiv Gandhi: A Son Who Won, Lost and Tried a Comeback” (May 1991). The New York Times. Retrieved from

http://www.nytimes.com/1991/05/22/obituaries/assassination-in-india-rajiv-gandhi-a-son-who-won lost-and-tried-a-comeback.html; Kaufman, Michael T. “Mrs. Gandhi Grooms Another Son” (June

1982). The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1982/06/13/magazine/mrs gandhi-grooms-another-son.html

67 Cerra, Valerie and Saxena, Sweta C. “What Caused the 1991 Currency Crisis in India?” (October 2000). International Monetary Fund, Working Paper 00/157. Retrieved from

http://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/30/What-Caused-the-1991-Currency-Crisis in-India-3794

68 Mukherji, Rahul. “The State, Economic Growth, and Development in India” (February 2009). India Review, 8:1, pages 81-106. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14736480802665238 69 International Monetary Fund. India BOP Net Financial Account (2016). Retrieved from Bloomberg terminal, 5343R001 Index

70 Raghavan, Srinivasa. “1991: The Real Villain Was Rajiv Gandhi, The Real Hero Was Not Manmohan” (July 2016). Swarajya. Retrieved from https://swarajyamag.com/politics/1991-the-real villain-was-rajiv-gandhi-the-real-hero-was-not-manmohan

71 Gupte, Pranay and Singh, Rahul. “Money! Guns! Corruption!” (July 1997). Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/forbes/1997/0707/6001112a.html

72 Reserve Bank of India. Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy (September 2016), Table 240: Select Fiscal Indicators of the Central Government (As Percentage to GDP). Retrieved from https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/PublicationsView.aspx?id=17373; Reserve Bank of India. Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy (September 2016), Table 242: Combined Deficits of Central and State Governments (As Percentage to GDP). Retrieved from

https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/PublicationsView.aspx?id=17375; Reserve Bank of India. Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy (September 2016), Table 243: Select Debt Indicators of the Central and State Governments (As Percentage to GDP). Retrieved from

https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/PublicationsView.aspx?id=17376

73 The World Bank, World Development Indicators (2017). Net official development assistance and official aid received (current US$). Retrieved from

http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/DT.ODA.ALLD.CD

74 Patel, I.G. “New Economic Policies: A Historical Perspective” (January 1992). Economic and Political Weekly, 27:1/2, pages 41-46. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41498726 75 The World Bank, International Debt Statistics (2017). External debt stocks, total (debt outstanding and disbursed, current US$). Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/DT.DOD.DECT.CD; The World Bank, International Debt Statistics (2017). External debt stocks, public and publicly guaranteed (debt outstanding and disbursed, current US$). Retrieved from

http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/DT.DOD.DPPG.CD

76 The World Bank, International Debt Statistics (2017). Total debt service (% of exports of goods, services and primary income). Retrieved from

http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/DT.TDS.DECT.EX.ZS

77 Ghosh, Atish and Ramakrishnan, Uma. “Current Account Deficits: Is There a Problem?” (March 2012). International Monetary Fund. Retrieved from

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/basics/current.htm

78 Powell, Benjamin. “Trade Deficit Is Really A Capital Surplus” (October 2006). Investor’s Business Daily. Retrieved from http://www.independent.org/newsroom/article.asp?id=1832

79 Clausen, Jens R. and Kandil, Magda E. “On Cyclicality in the Current and Financial Accounts: Evidence from Nine Industrial Countries” (March 2005). International Monetary Fund, Working Paper 05/56. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=MoMrdKIk6HQC

80 Sharma, Shalendra D. China and India in the Age of Globalization (July 2009), Chapter 2: China and India Embrace Globalization. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from

https://books.google.com/books?id=3c8hAwAAQBAJ

81 Khanna, Tarun. Interview with Suresh Krishna (December 2012). Harvard Business School, Baker Library Special Collections, Creating Emerging Markets Oral History Collection. Retrieved from http://www.hbs.edu/creating-emerging-markets/interviews/Pages/profile.aspx?profile=skrishna 82 Das, Gurcharan. India Unbound (April 2002), Chapter 11: Multiplying By Zero. Anchor Books. 83 The Economist. “Who put the shine into India?” (May 2004). Retrieved from

http://www.economist.com/node/2705880

84 Boughton, James M. Tearing Down Walls: The International Monetary Fund, 1990-1999 (February 2012), Chapter 9: Five Fat Years: Recovery from the Debt Crisis, 1990-94. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/history/2012/pdf/c9.pdf 85 Singh, Manmohan. “Budget 1991-92 Speech” (July 1991). Government of India, Ministry of Finance. Retrieved from http://indiabudget.nic.in/bspeech/bs199192.pdf

86 The balance of payments also includes a third, typically minor component: the capital account, which records non-market transactions (such as debt forgiveness), as well as international exchanges of non-produced assets (such as wireless spectrum or land purchased for embassies). This memo uses the terminology employed by the IMF, which designates the “capital account” as a distinct third component of a nation’s balance of payments. Note that certain academic and media organizations use the term “capital account” as a broad category encompassing the components of both the “financial account” and the “capital account”, as defined here. Council of Economic Advisers. “Economic Report of the President” (February 2004), Chapter 14: The Link Between Trade and Capital Flows. U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/ERP/pages/8853_2000-2004.pdf

87 Dua, Pami and Ranjan, Rajiv. “Exchange Rate Policy and Modelling in India” (February 2010). Reserve Bank of India, Department of Economic Analysis and Policy, Development Research Group. Retrieved from https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/PublicationsView.aspx?id=12252

Legal information and disclosures

The views expressed are the views of the author as of the date indicated on each posting; such views are subject to change without notice. Farley Capital L.P. (Farley Capital)has no duty or obligation to update the information contained herein. Further, Farley Capital makes no representation, and it should not be assumed, that past investment performance is an indication of future results. Any discussion regarding investment returns or financial projections are provided as illustrative examples only and no inference shall be made therefrom regarding the potential for returns on any investment discussed. Moreover, you should be aware that all types of investments involve a significant degree of risk, and wherever there is potential for profit, there is also the possibility of loss.

This content is being made available for informational and educational purposes only and should not be used for any other purpose. The information contained herein does not constitute and should not be construed as financial, legal, or tax advice, or as an offering of advisory services. The information contained herein shall not constitute an offer to sell, or a solicitation to subscribe for, interests in any investment vehicle managed by Farley Capital, which offer or solicitation will only be made to qualified investors and accompanied by a private placement memorandum, subscription agreement, and other related offering documents. Certain information contained herein concerning economic trends and performance is based on or derived from information provided by independent third-party sources. Farley Capital believes that the sources from which such information has been obtained are reliable; however, it cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of such information and has not independently verified the accuracy or completeness of such information or the assumptions on which such information is based.

This content, including the information contained herein, may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted in whole or in part, in any form without the prior written consent of Farley Capital.